One Family’s Story of Survival Under the Khmer Rouge, No Longer Buried

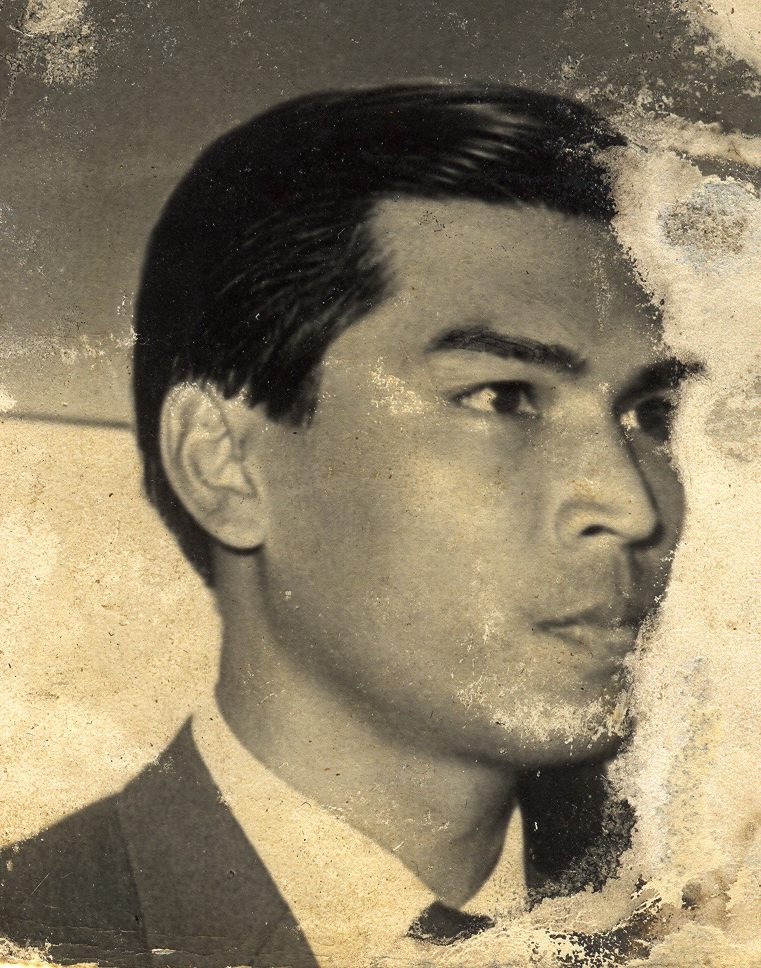

Photos testify to the Rama’s journey from Battambang to Shreveport.

Though 10-year-old Vira Rama didn’t understand what his family’s secrets were, he knew that they had to be kept hidden. At first glance, they seemed innocuous enough: a stash of family photos of trips to the beach and Siem Reap, a photo of Rama in a youth scout uniform, all wrapped up in a bag made of cut tarp.

When the Khmer Rouge seized control of the country in April 1975, Rama’s mother, Kim Pean Ky, had insisted on taking this bundle of photos with her as her family was forcibly relocated from their home in the northwestern city of Battambang. She kept them concealed as soldiers marched them into the country on dusty roads congested with people fleeing in three-wheeled tuk-tuks, on ox-driven carts, and even on foot. As soon as the family was resettled in a village called O’ Srarlao, located in what the military regime called Zone 4, Rama watched as his mother dug a hole under their small wooden hut just large enough for the bag of photos. He didn’t ask questions as she hid the traces of their middle-class life under a pile of banana leaves. Though the family would travel to several other zones during the rule of the Khmer Rouge, from 1975 to 1979, Rama’s mother never forgot about the photos. Each time they moved, she quietly and dutifully excavated the bag and then buried again, and again, and again. If the severe, unpredictable, paranoid Khmer Rouge had found it, their lives would be forfeit.

Now, 44 years later, the archive Rama’s mother risked her life to preserve has been published in a book, aptly named Buried. The book is a collaboration between the family and British photographer Charles Fox, who has worked in Cambodia since 2005 running Found Cambodia, an archive of photos of life before, during, and after the reign of the Khmer Rouge in the late 1970s. Of all the photos Fox has encountered in Found Cambodia, he says the Rama’s archive is by far the most complete. “Their story is one of thousands of stories,” he says. “But their collection is unique. Vira tried to record as much of his family history as possible.”

“I feel lucky to have these photos,” says Rama, who held on to Ky’s archive long after the family relocated to the United States (both now live in Southern California). “It gives me something to go back to. Many people who survive the Khmer Rouge have nothing at all.”

Rama was born in 1965 in Battambang. The second-eldest of seven siblings, he lived a charmed early life that was assiduously documented by his father. “I liked being photographed. I was always the goofy one,” he says, adding that many of his childhood photobombs did not make the cut for Buried. In Battambang, before their forced relocation, the photos lay behind plastic in albums and hung on the walls in frames. The tarp bag provided less protection, and many of the photos were damaged. Rama’s mother also altered some of the photos that would have been impossible to explain her way out of, had they been found. For example, she cut King Norodom Sihanouk—who had a complicated and fraught relationship with the Khmer Rouge—out of a photo of her husband.

In the camps, the photos had to be buried because Khmer Rouge soldiers conducted random searches of people’s huts to purge any evidence of city life. Other families also concealed treasures that could get them killed, such as jewelry or medicine, which indicated you were wealthy enough to have seen a doctor. O’ Srarlao’s Zone 4 became one of the most brutal areas controlled by the Khmer Rouge. In addition to executions, the villages were rife with starvation and disease made worse by forced labor.

At O’ Srarlao, the family slowly splintered as children were sent to perform forced labor at different camps, some planting rice and others constructing irrigation systems. Despite the family’s best efforts to conceal their history, Rama’s father stood out as a target for the Khmer Rouge, which actively persecuted and murdered intellectuals. A former math and French language teacher who worked as a banker for the Banque Khmere Pour Le Commerce, he was a member the class that the new regime saw as an existential threat. In 1977, he was executed.

Shortly after, the Ramas knew they had to leave the country. The family members remaining at Zone 4 split into three groups, Ky dug up the photos and fled with some of her seven children to the less violent Zone 3, reburying the photos in each village they stayed in. “My mom valued these photos even though it was risky evidence,” Rama says. “If they searched us, they would kill us.”

When Vietnamese forces liberated the country in 1979, the Ramas reunited in Battambang. But Khmer Rouge soldiers still lurked, and so they fled once more through jungles and minefields to the Thai border. They arrived in 1980 and settled in the Khao-I-Dang refugee camp. After 18 months there, they found a sponsor in the United States. After a few months in the Philippines to learn English, the Ramas moved to Shreveport, Louisiana, in 1981. Rama had just turned 16. Buried contains photos of these unsettled but peaceful times, both at the refugee camp and during the family’s first few years in America.

In Louisiana, Ky worked various jobs—as a seamstress, in a spice factory, at restaurants. Her seven children went to school. Rama attended Warren Easton High School, the first time he’d been in school for six years, and graduated in 1985. With the help of his math and science teacher Mr. Blanchard, Rama became a civil engineer.

Around a year after Rama’s family arrived, his sponsor gave him a cheap camera. It was the first time Rama had held a one since before the Khmer Rouge took over. Later in life, he upgraded to a series of fancy digital cameras, including a Nikon DSLR he used to snap photos of his children in soccer and basketball games. Taking photos had become an everyday luxury, and Rama errs on the side of over-documentation.

Rama’s love of photography made him the family’s photokeeper. He kept all his family’s photos in a safety deposit box and scanned many to upload to Flickr—glimpses of life before and after the Khmer Rouge. He also kept artifacts of his family’s immigration, such as the Pan Am tickets they used to fly to America. In 2015, he stumbled upon Found Cambodia, Fox’s project. “I sent Charles an email with a link to my Flickr, saying he was more than welcome to take any photos to add to his collection,” Rama says. “The very next day he emailed me back.”

Fox had dozens of questions. Who were the people in the photos? Where were they taken? Who did the photos belong to? Fox recognized that Rama possessed an incredible document of a time mostly lost to history. “Other family’s photos are so fragmented, which have their own importance,” Fox says. “But what the Ramas managed to save and how they managed to survive is quite remarkable.”

The horrors of the Khmer Rouge are hard to imagine, in part because there are almost no surviving photos of what life was like under the military regime due to the regime’s eschewal of modern life. The most known pictures of that period consist of 7,000 portraits taken by Nhem Ein, a young photographer working in the Tuol Sleng prison, according to The New York Times. It is a grim collection, as every portrait is of a person about to be executed.

When Fox saw all of Rama’s archive, he was struck by its narrative cohesion—a family’s story. He proposed the photos be arranged in a simple booklet, and all members of the Rama family were game. “He consulted with me every step, from the color to the title,” Rama says. The book’s design is intentional: The inside covers are decorated with rumdul flowers, the national flower of Cambodia, and pages that separate life before and after the Khmer Rouge are blank and red.

When Fox sent Rama the first draft of the book, the photos were arranged without any identifying details. Fox asked if Rama’s family could jot down quick captions noting who was in each photo and what occasion, if any, it captured. Rama passed the manuscript to his relatives, who each wrote a few lines in blue pen under the photos that were most meaningful to them. Those handwritten captions appear in the final book—occasionally illegible and deeply human. “That’s how close the family is,” Fox says. “And that’s one of the things that made the book possible.”

Now, each year, the family—Ky, Vira Rama, his six siblings and their families—go camping. Sometimes it’s Mammoth Lakes, sometimes it’s Yosemite. Rama says his relatives often jokingly complain. “They say, ‘We escaped all this hardship, why are we going to spend a week in a tent?’ But maybe that’s part of the healing.” On these trips, the family cooks what Rama calls their native food: cajun and creole cuisine—gumbo, jambalaya, red beans and rice. Unsurprisingly, Rama takes photos of everything. Now that he’s older, he’s traded his fancy DSLR for a lighter antique Fujifilm.

In Rama’s eyes, Buried is a historical document with very modern echoes. Over the past year, he can’t help but spot the parallels between his own family’s harrowing escape and the current situation at the U.S.-Mexico border. He says images of caravans attempting to cross into America bring flashbacks to the fear and violence he experienced as a child. “These people just want a better life for themselves and their children,” he says. “Here in America we’re supposed to be the most generous country but we treat refugees like criminals.”

Cambodia is struggling as well, in particular with its history, according to The Nation. “A lot of millennials in Cambodia don’t know what happened under the Khmer Rouge,” Rama says. “They think it’s fake news.” He hopes Buried will continue to open up new conversations both in the United States and Cambodia about this violent chapter of history. He understands that his family’s journey is not unique, but their records are, and he hopes other Cambodian families will continue to learn their history and break cycles of trauma that afflict generations.

Rama has worked for the city of Los Angeles for 29 years now, and he says he’s five years away from retirement. Recently, he’s noticed more and more people telling him to go back where he came from. “I ask them, which way should I take?” Rama says. “The road I just built, or the other road I built?”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook