Remembering When Americans Picnicked in Cemeteries

For a time, eating and relaxing among the dead was a national pastime.

Within the iron-wrought walls of American cemeteries—beneath the shade of oak trees and tombs’ stoic penumbras—you could say many people “rest in peace.” However, not so long ago, people of the still-breathing sort gathered in graveyards to rest, and dine, in peace.

During the 19th century, and especially in its later years, snacking in cemeteries happened across the United States. It wasn’t just apple-munching alongside the winding avenues of graveyards. Since many municipalities still lacked proper recreational areas, many people had full-blown picnics in their local cemeteries. The tombstone-laden fields were the closest things, then, to modern-day public parks.

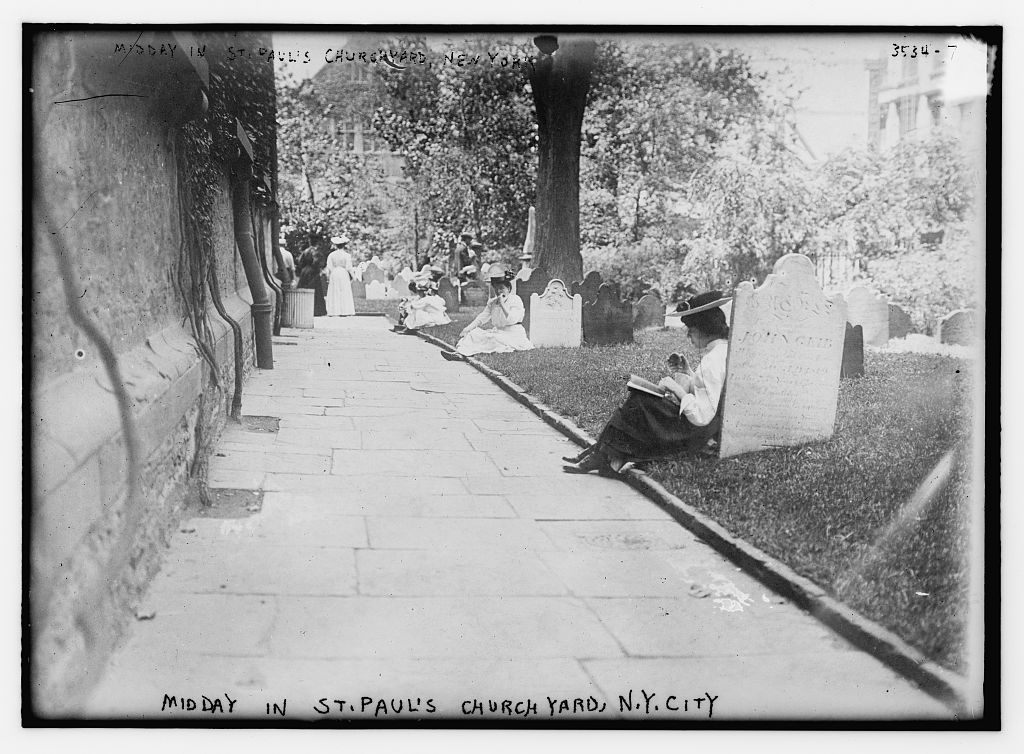

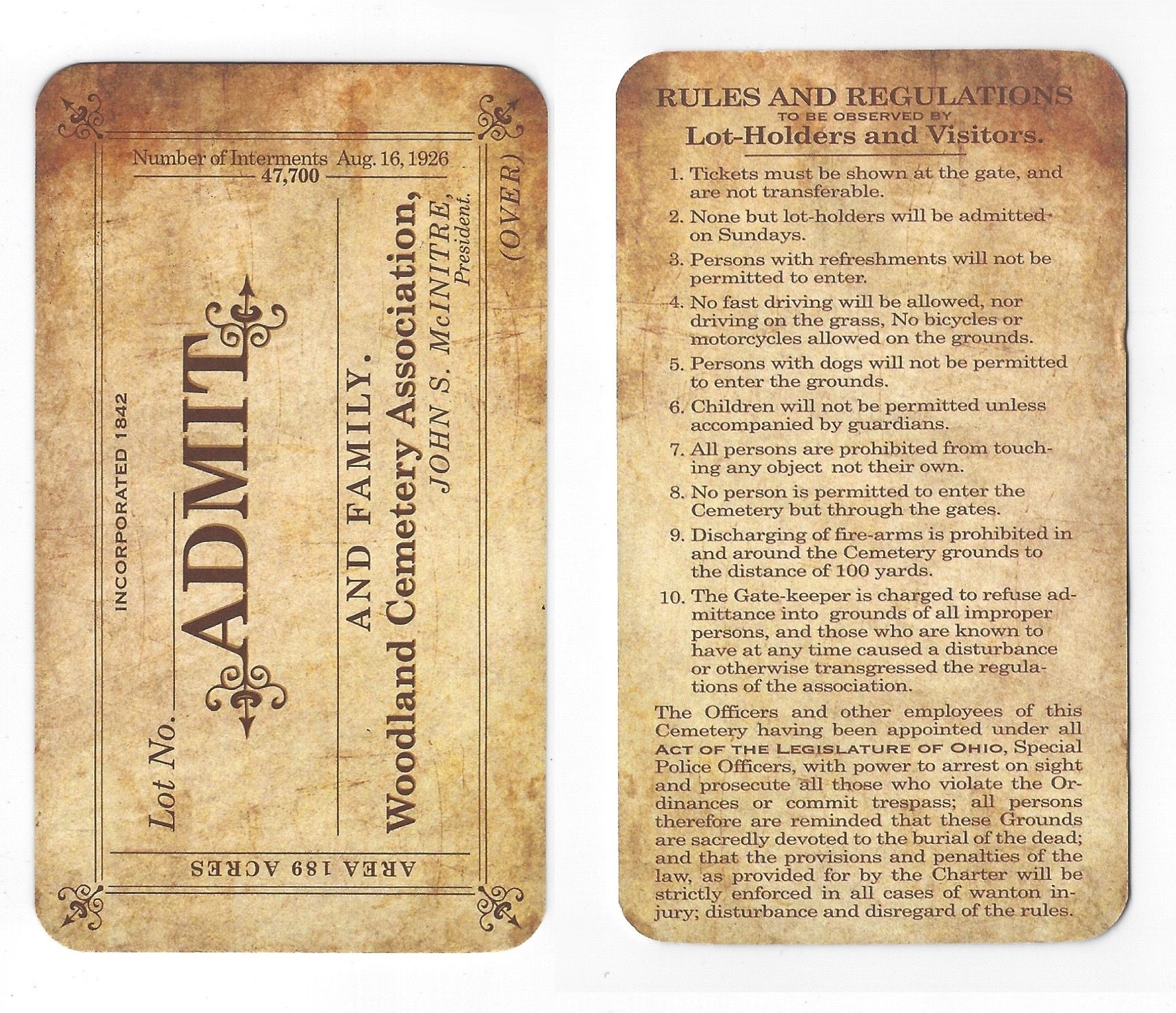

In Dayton, Ohio, for instance, Victorian-era women wielded parasols as they promenaded through mass assemblages at Woodland Cemetery, en route to luncheon on their family lots. Meanwhile, New Yorkers strolled through Saint Paul’s Churchyard in Lower Manhattan, bearing baskets filled with fruits, ginger snaps, and beef sandwiches.

One of the reasons why eating in cemeteries become a “fad,” as some reporters called it, was that epidemics were raging across the country: Yellow fever and cholera flourished, children passed away before turning 10, women died during childbirth. Death was a constant visitor for many families, and in cemeteries, people could “talk” and break bread with family and friends, both living and deceased.

“We are going to keep Thanksgivin’ with our father as [though he] was as live and hearty this day [as] last year,” explained a young man, in 1884, on why his family—mother, brothers, sisters—chose to eat in the cemetery. “We’ve brought somethin’ to eat and a spirit-lamp to boil coffee.”

The picnic-and-relaxation trend can also be understood as the flowering of the rural cemetery movement. Whereas American and European graveyards had long been austere places on Church grounds, full of memento mori and reminders not to sin, the new cemeteries were located outside of city centers and designed like gardens for relaxation and beauty. Flower motifs replaced skulls and crossbones, and the public was welcomed to enjoy the grounds.

Eating in graveyards had, and still has, historical precedent. People picnic among the dead across the world, from Guatemala to parts of Greece, and similar traditions involving meals with ancestors are common throughout Asia. But plenty of Americans believed that picnics in local cemeteries were a “gruesome festivity.” This critique, notably from older generations, didn’t stop young adults from meeting up in graveyards. Instead it led to debate over proper conduct.

In some parts of the country, such as Denver, the congregations of grave picnickers grew to such numbers that police intervention was even considered. The cemeteries were becoming littered with garbage, which was seen as an affront to their sanctity. In one report about these messy gatherings, the author wrote, “thousands strew the grounds with sardine cans, beer bottles, and lunch boxes.”

Though the macabre picnics were considered “nuisances” in some communities, they did give participants a sort of admired air. One reporter lauded the fact that the picnickers looked “happy under discouraging circumstances,” and even said it was a trait “worthy of cultivation.” The fad of casual en plein air dining among the crypts would soon come to an end, though.

Cemetery picnics remained peripheral cultural staples in the early 20th century; however, they began to wane in popularity by the 1920s. Medical advancements made early deaths less common, and public parks were sprouting across the nation. It was a recipe for less interesting dining venues.

Today, more than 100 years since Americans debated the trend, you’d be hard-pressed to find many cemeteries—especially those in big cities—with policies or available land that allow for picnics. Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, for example, has an explicit no-picnicking rule.

But the fad isn’t entirely dead in the United States. The country’s immigrant population includes communities carrying on traditions that call for meals with departed loved ones, and cemeteries will hold occasional public events in the spirit of an earlier era. There are still scattered graveyards where you can picnic among tombstones, too, particularly if you know someone with a sizable family lot. In those cases, all you need is a picnic basket filled with treats, and you and your undaunted party can partake in an old American tradition. Just remember to clean up after yourselves. The penalties for doing otherwise may be grave.

This story originally ran on April 20, 2018. It was updated, with light edits, on October 13, 2021.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook