What We Can Learn From Pluto’s Icy Heart

The celestial snowball’s most stunning feature might be cold, but it sure isn’t dead.

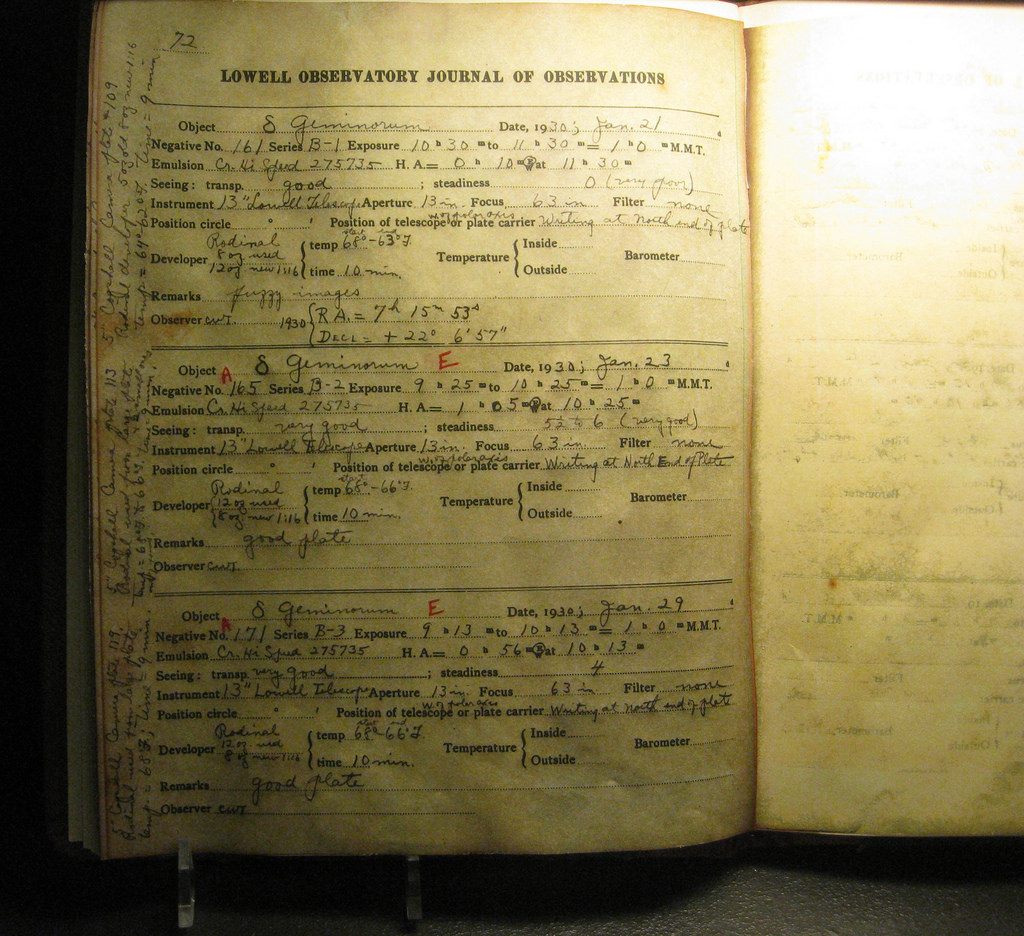

On February 18, 1930—87 years ago this week—Clyde Tombaugh, a telescope operator at Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, was flipping through photo plates when he spotted what he had been seeking for months. Tombaugh, just 24 years-old at the time, had been given the tedious job of searching for a new planet: Every night, he would take long-exposure images of the night sky, and every day, he would compare photos taken a few nights apart.

Among the tens of thousands of pinpricks of light in the images he was examining, most stayed in the same position from one day to the next, giving away their status as stationary stars. But one tiny dot was moving, progressing along its orbit, blithely unaware of the young astronomer who was about to find it out. “It electrified me,” Tombaugh later remembered. “When I saw that, I knew instantly that was it.”

Tombaugh had been searching for the fabled Planet X, which orbital math suggested was several times heavier than Earth. This, instead, was Pluto, a heavenly body so tiny, it’s not even technically a planet. It was so much smaller than expected that Tombaugh passed it over entirely on his first few sweeps of the sky. He might have missed it for good if it weren’t for one thing: its shiny heart.

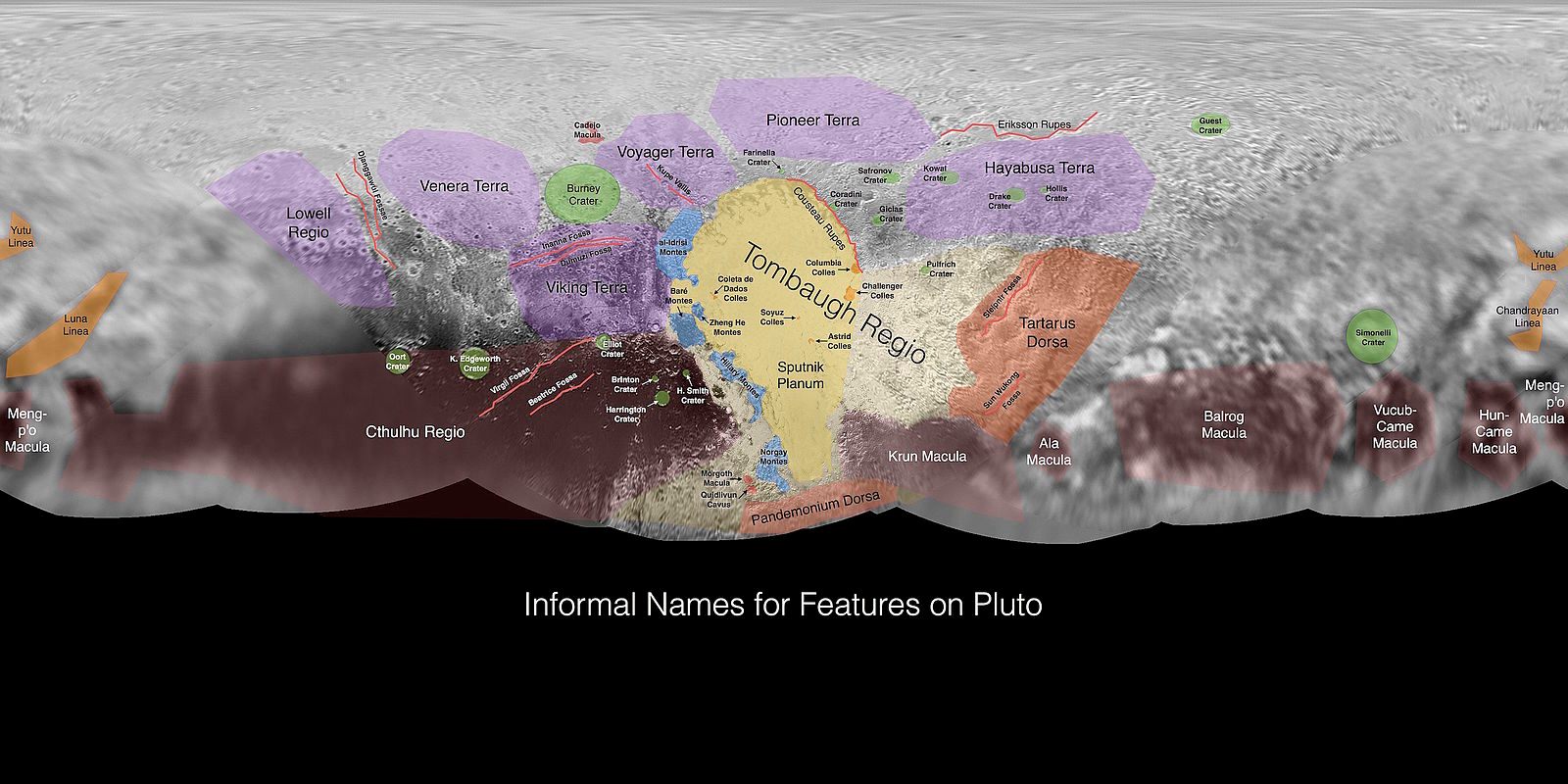

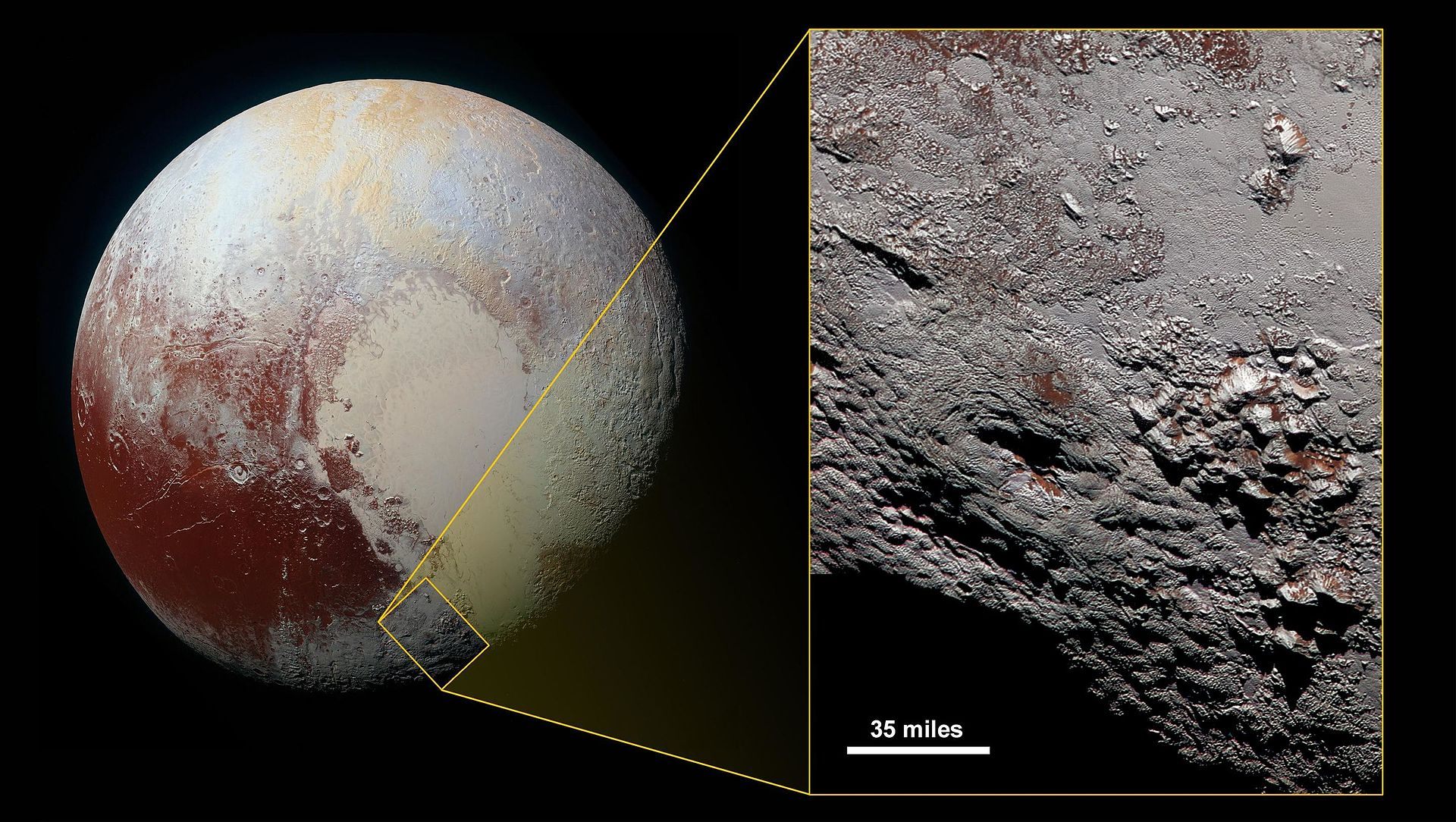

Pluto’s heart—also known as the Tombaugh Regio, after the man who first spotted it—is a wide, smooth swath that covers about 990 miles of the dwarf planet’s surface. We Earthlings first saw it clearly in July of 2015, when NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft beamed back a set of up-close Pluto portraits. As interplanetary messaging, this was nearly as romantic as Saturn’s rings. “Pluto has sent a ‘love note’ back to Earth,” NASA reported. Memes proliferated, showing the planet holding its heart out to Earth, begging for acceptance back into the planetary ranks.

But the heart meant even more to astronomers and geologists—it was proof that Pluto was, in a sense, “alive.” “In your worst nightmare, you’d have convinced NASA to go all the way to the end of the solar system and you’d have a cratered ball,” New Horizons team member Bill McKinnon told New Scientist in 2015. Although Pluto has its share of pockmarked, dead-looking surface area, the Tombaugh Regio is anything but.

Its western lobe, called the Sputnik Planitia, is a massive basin covered in nitrogen ice—a dense, volatile material that, at Pluto’s temperature of 40 degrees Kelvin, is prone to forming slowly shifting glaciers. These glacial plains are strewn with strangely shaped columns, which might indicate a cycle of nitrogen snowfall. Two large, scoop-topped cones just off the southern tip of the heart may even be ice volcanoes.

Overall, the region’s lack of craters indicates that it smoothed itself over sometime within the last 10 million years, a brief tick in solar-system time. New research suggests that we’ll be able to see the glaciers flowing out and retracting over the next few decades—it will look, one scientist said, like a heartbeat.

Astronomers continue to investigate just what makes Pluto’s heart tick. Some, though, are also taking it as a prod to venture even farther afield. The Kuiper belt—the huge scattering of ice chunks and space detritus where Pluto lives—is home to at least three more dwarf planets, called Haumea, Makemake, and Eris. Previous wisdom held that they were just too frozen to be dynamic, but the findings about Pluto’s heart—cold, but still beating—are overturning this assumption. “There’s no reason that many of the others, maybe all of the others, shouldn’t do the same,” New Horizons team leader Alan Stern told New Scientist.

Eighty years ago, Pluto’s shiny heart beckoned us out to the edges of the solar system. Now, closer examination of it might inspire us to look even farther.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook