For Sale: A Poisoner’s Lab Secreted in a Beautiful Book

Another reminder that covers can’t be trusted.

If you need a place to hide a secret stash, you have a few options. There’s the standard subterranean vault, protected by stairs, bolts, and darkness. Or maybe a hole somewhere remote and untrammeled, insulated by both vegetation and inconvenience. If you want to easy access—a secret in plain sight, with a bit of a wink—there’s the classic piece of spycraft, the hollowed-out book.

These sneaky little treasuries go by many names, including “book safes.” They’re easy enough to buy, or even make, and they’re useful for all kinds of things besides holding a secret: corralling cords and remote controls, storing a little cash for a rainy day, or keeping a treasured memento.

Unsurprisingly, not-quite-books have sometimes served nefarious aims. In the 1960s, two kids in New Haven, Connecticut, took a razor blade to a 400-page tome and then wandered in and out of shops, stowing little stolen items along the way. The following decade, a man tucked a gun inside a hollowed copy of The Rich Are Different, and used it to rob a bank in Mount Vernon, New York. (Bond villain Red Grant did something similar in the 1963 film From Russia With Love, slyly hiding a gun inside a copy of War and Peace.) And for one creative person in 19th-century Germany, a book safe may have been perfect place for an arsenal of “poisons.”

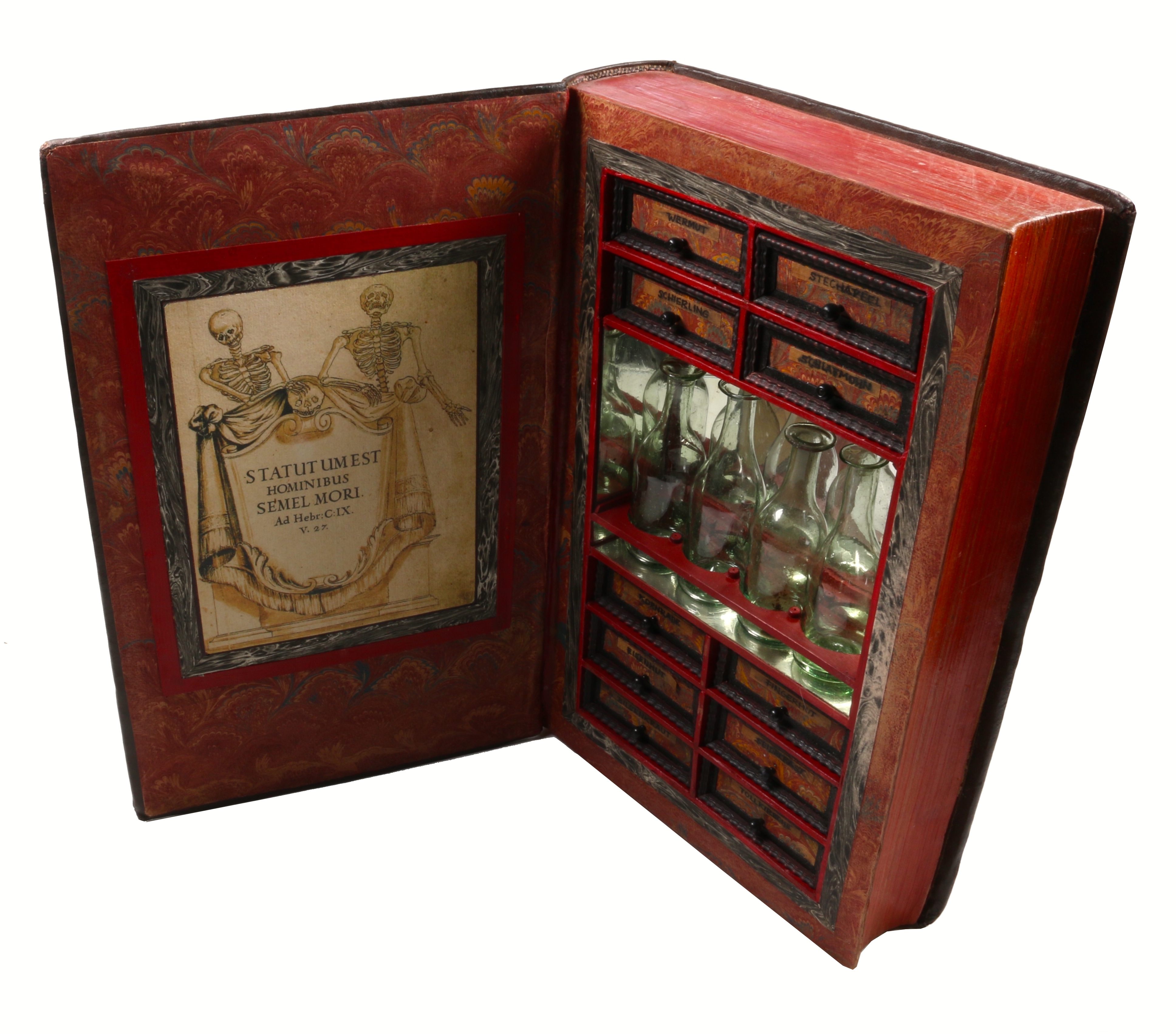

At first glance, this object would be right at home on any shelf, with the binding and block that appears to be from a volume by Portuguese theologian Sebastião Barradas, published posthumously in 1640, according to INLIBRIS, an antique bookseller based in Vienna. But crack it open, and things look quite different—and extremely macabre.

It is lined with red, marbled paper. On the inside cover, two skeletons hold a banner reading: “Statutum est hominibus semel mori,” or “All people are destined to die once.” It’s Hebrews 9:27, and it wouldn’t be nearly as ominous if it wasn’t next to 10 little drawers labeled with names of poisonous plants, and a mirrored shelf holding several little glass bottles.

The compartments bear the German names for hemlock, wolfsbane, foxglove, and more—all lethal, properly administered—and the suggestion seems to be that the little vials are there for a would-be poisoner to mix up their own deadly cocktails.

The team at INLIBRIS is currently offering this morbid curio via AbeBooks. The truth behind it might be less exciting than the appearance, as the sellers believe it was likely a 19th-century prank that used 17th-century supplies. Putting a precise date on these types of assembled objects can be tricky, because “they’re all meant to look old,” says book conservator Mindell Dubansky, author of an actual book called Blook: The Art of Books That Aren’t. This item may have been a novelty or a souvenir, reaching for an older aesthetic to boost its cachet. In any event, there’s no indication that the fake book ever really killed anyone.

While book-like objects with a medical bent or a whiff of the wunderkammer aren’t total anomalies—Dubansky has seen old bloodletting kits and microscope slides stored this way—this particular take on the concept is “a real curiosity,” says Timothy Young, curator of modern books and manuscripts at the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale University, in an email. “I’ve not seen anything like it.” If you can part with nearly $11,000, this grim little wonder can sit on your bookshelf. Please use it responsibly.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook