The Endlessly Adaptable Skeletons of José Guadalupe Posada

Calaveras created by the Mexican artist have been repurposed for generations, with wildly varying intent.

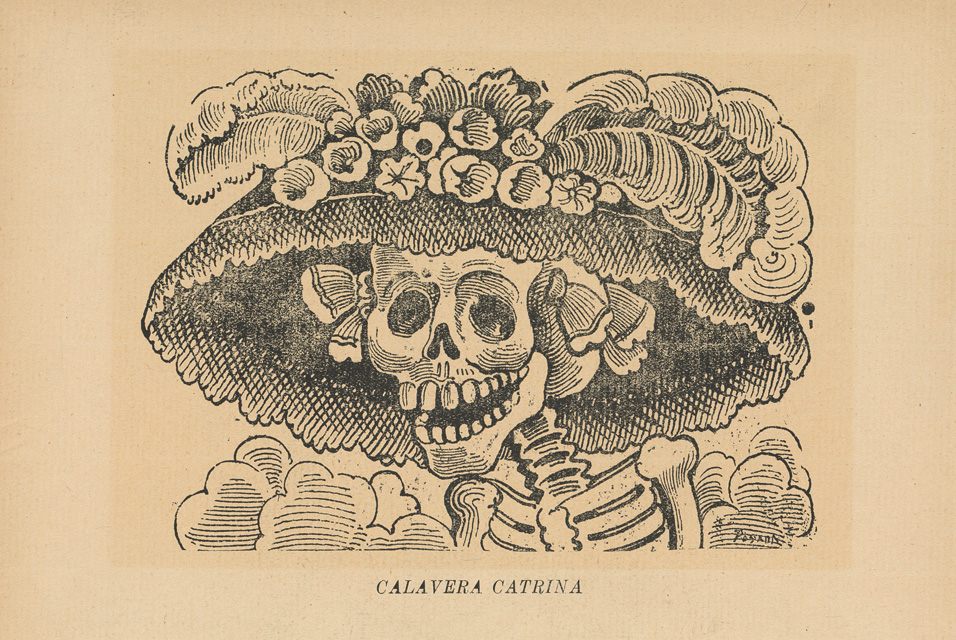

You may recognize the image above. It’s a difficult one to forget: a laughing skeleton in a flowery hat. You might have seen her in Diego Rivera’s iconic mural, Sueño de una Tarde Dominical en la Alameda Central (Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in the Alameda Central). There, she links arms with a likeness of her creator, José Guadalupe Posada. Or you might have spotted her in the Disney/Pixar film Coco, taking the hand of the main character in order to guide him into the Land of the Dead.

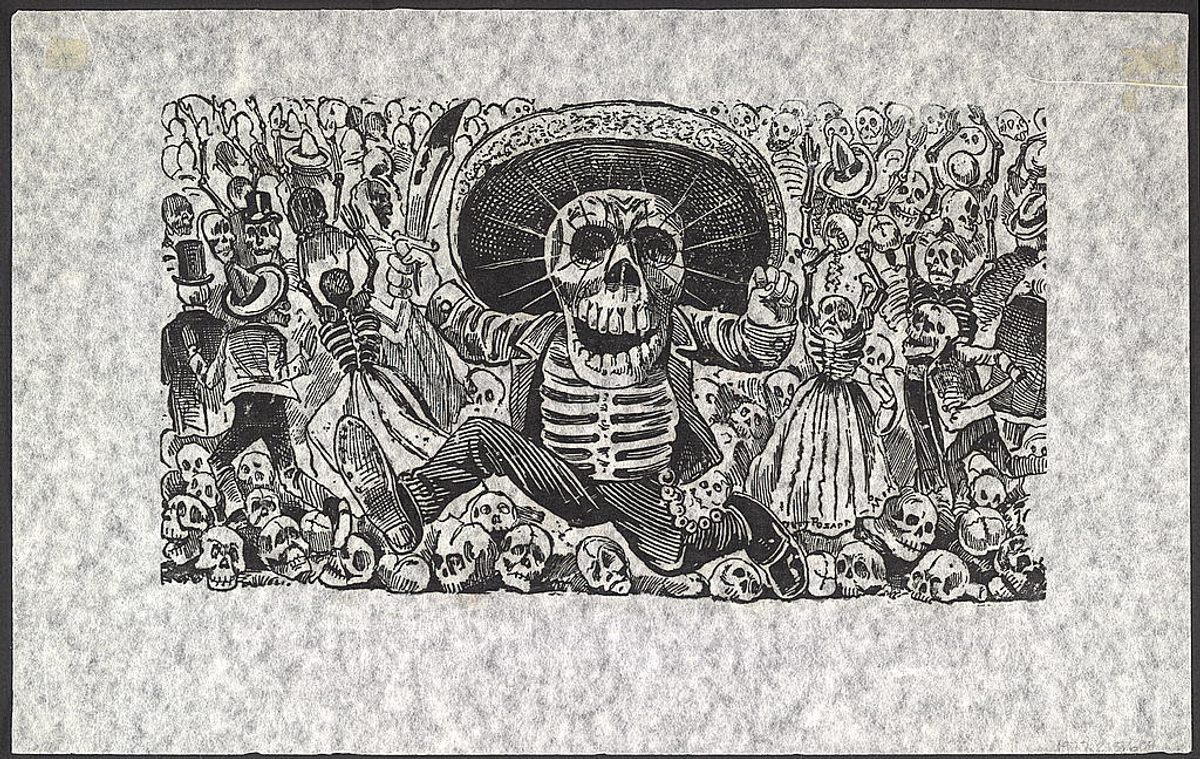

This skeleton, known as “La Catrina,” is one of Posada’s best-known calaveras: illustrations of skeletons, boldly drawn and thickly inked, and much more energetic and expressive than you’d expect, given their biological state. Although the figures have become closely associated with the holiday Dia de Muertos (Day of the Dead), Posada originally drew his calaveras as political cartoons, commenting on various issues of the day. (“La Catrina,” for instance, was meant to poke fun at early 20th century Mexican women who imitated European fashions.)

Over the century or so since they were first created, though, these calaveras have thrown off the shackles of their initial context. They’ve been repurposed by artists to express ideas and opinions across the political spectrum, as well as by advertisers, animators, and activists. For skeletons, they live a whole lot of different lives.

Although he is the most famous illustrator of them, “Posada did not invent the calavera,” says the cartoonist and activist Rafael Barajas Durán. As Regina Marchi writes in Day of the Dead in the USA, images of skulls and skeletons have long been a part of Mexican culture, particularly in the context of Day of the Dead celebrations. (The decorative sugar skulls and darkly funny poems associated with the holiday are both also called “calaveras,” which is Spanish for “skulls.”)

As Durán explains, the skeleton drawings that now go under that name first began appearing regularly in Mexican publications in the 19th century, particularly in journals like La Orquesta, which was known for its biting political satire. “They celebrate the moment when [the country] opened the civil cemeteries,” Durán says. “Before that, all cemeteries in Mexico were the property of the church.” Marchi also points out a connection to the the Danse Macabre, a European motif in which skeletal figures demonstrate various intense, sometimes comical emotions while dancing to their graves. Other scholars trace them even further back, to Aztec depictions of gods and goddesses of the dead.

Like his creations, Posada himself has a complicated and multi-layered legacy. He was born in 1852 in Aguascalientes, Mexico. Not much is known about his early life, although experts think he was first exposed to design work at his uncle’s ceramics studio and a local drawing school. By the 1880s, when he began working as an illustrator at La Patria Ilustrada—run at the time by Ireneo Paz, Octavio Paz’s grandfather—it wasn’t unusual to see skeletons cavorting across newspaper pages.

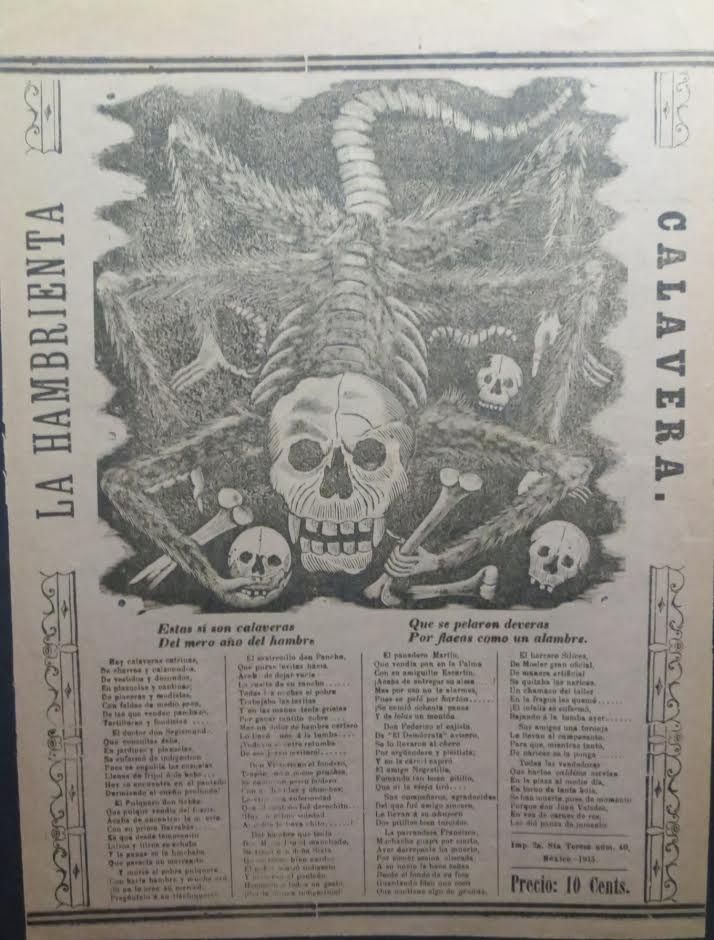

Over the next few decades, Posada worked for a number of publications, making lithographs and woodblock prints. As a hired illustrator, he was prolific by necessity. “There were little publications all around Mexico City at that time,” says Jim Nikas of the Posada Art Foundation. “They would say, ‘Hey, could you make this?’ And he’d have a deadline, and he’d sketch it and make it, and it would go to press.”

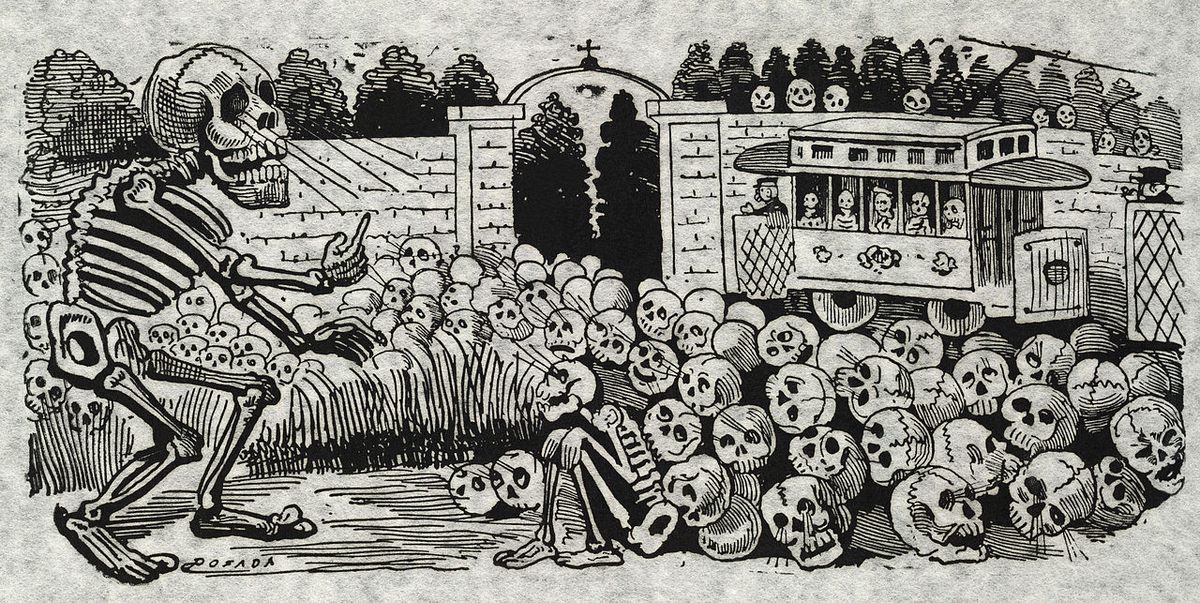

Influenced by his fellow artist Manuel Manilla, he developed a distinct style, bold and high-energy, that set him apart. (“His calaveras are wonderful,” says Durán.) He eventually became the head illustrator for Antonio Vanegas Arroyo’s print shop in Mexico City. Often, his illustrations appeared on one-sheet broadsides, accompanied by playful verses that connected them to the issues of the day.

Although Posada’s work spread far and wide, he did not find fame during his lifetime. He died in 1913, “practically alone,” says Durán. “He was not a very well-known artist. He was a popular phenomenon, but he was not acknowledged by … other cartoonists.”

It wasn’t until about a decade later, in the 1920s, that tastemaking artists like Jean Charlot and Diego Rivera began to promote his work. “Since nobody knew about Posada’s life, they made it up,” says Durán. “They made up the idea that he was a revolutionary,” which was likely not true. In a way, they did for Posada what Posada had done for calaveras: they took him, changed him a bit, and cemented him into the popular consciousness.

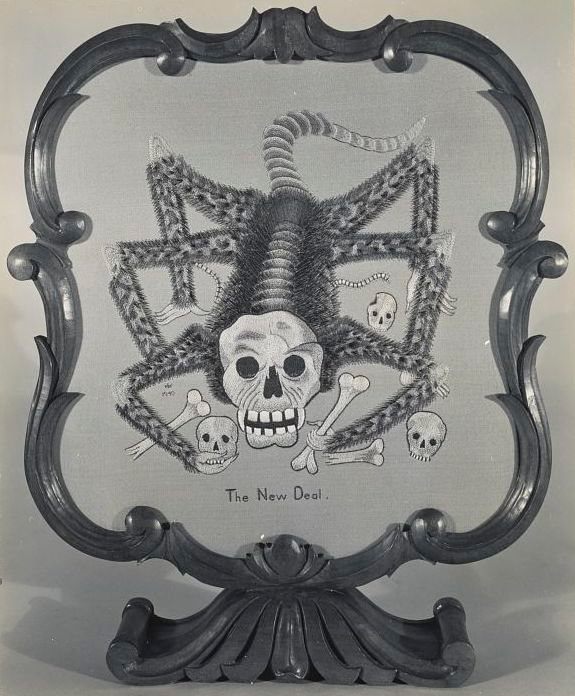

Meanwhile, other artists were still making calaveras. Many of these were stylistically inspired by Posada, sometimes so much so that they were mistakenly attributed to him. (One of these is La Calavera Huertista, a drawing of a many-legged, skull-headed creature surrounded by the wreckage of other, half-devoured calaveras. Named for Victoriano Huerta, a general who helped overthrow the Mexican President, the drawing referred to events that happened after Posada’s death.)

In the late 1930s, an artist’s collective called The People’s Workshop formed in Mexico City. “They used calaveras left right and center,” to promote communism, antifascism, and other political ideas, says Nikas.

As time went on, calaveras spread further, and began showing up in unlikely places. One fan was Eleanor B. Roosevelt, a photojournalist and seamstress and the wife of Teddy Roosevelt’s son, Theodore Roosevelt, Jr. As described in an earlier Atlas Obscura article, during the Republican National Convention, Roosevelt began stitching a version of La Calavera Huertista. She eventually labeled the scorpion creature “The New Deal,” after the Democratic legislation she and her husband disagreed with.

To all appearances, Roosevelt was drawn to the aesthetic and form of the calavera, separate from its history and message. In her memoir, Day Before Yesterday, Roosevelt describes herself as having a “taste for the unearthly and the macabre.” She also apparently made a habit of borrowing and recontextualizing imagery in this way: In the same memoir, Roosevelt describes basing her embroidery on everything from “Chinese paintings” to “such ancient and modern artists as Bosch, Brueghel, Artzybasheff, and Charles Baskerville.” There is at one other case where she appended a current events-related caption to an unrelated image, stitching “Recognition of U.S.S.R. 1933” beneath a Russian market scene.

It’s unclear where Roosevelt came across La Calavera Huertista, or got a copy to study. Durán and Nikas both suspect she might have seen the Monografia, a compilation of sketches attributed to Posada that was put together in 1930 by the press Mexican Folkways, and which found some popularity in the United States. (Because the image was originally attributed to Posada, it was featured in the book.) It’s also unclear why Roosevelt told the International News Service that she had “devised” the scorpion image, rather than appropriating it from an existing work.

But purposefully or not, Roosevelt was taking advantage of another vital aspect of calaveras: their malleability. Over the years, these images have constantly been repurposed for various means. “[Posada] himself used to do that quite often,” says Durán, citing another famous design: the “Calavera Madero,” which depicts the former Mexican President as a straw-hatted skeleton with a blanket thrown over his shoulder. “It was printed several times for different purposes,” he says—first with a text that criticized him, and then, after he won the Mexican Revolution and became President, with one that praised him. The drawings were so adaptable that “he published them at different times, with different intentions.”

After Posada died, other artists at the printing house reused his blocks, too. “If the image was neutral enough, you could change the text and use it as an illustration for any story,” as a time- and cost-cutting measure, says Nikas. “To this day, that goes on,” as new generations repurpose, remix, and riff off of Posada’s work.

Take Rivera’s Sueño de una Tarde Dominical en la Alameda Central, which went up at the Hotel Prado in Mexico City in 1947. In it, La Catrina is transformed from a figure of fun into the centerpiece of a complex, surreal retelling of Mexican history. This sparked a kind of rebranding, and helped La Catrina take her current place as a symbol of cultural pride. (Some say Rivera even rechristened the image, which used to be called “La Calavera Garbancera.”) In the present, as Marchi writes, the image is “endlessly reproduced on Day of the Dead promotional flyers and T-shirts,” and “the original social commentary [has been] largely lost on the general public.”

Or take pioneering Chicana artist Ester Hernández’s 1982 screenprint Sun Mad, made to protest the overuse of pesticides endangering Mexican-American farm workers in California. It looks just a red Sun-Maid raisin box, but the slogan reads “Unnaturally Grown With Insecticides, Miticides, Herbicides, Fungicides,” and the smiling face of the Sun-Maid Girl has been replaced with the skeletal head of La Catrina. (In a 2012 version, Sun Raid, the calavera wears a monitoring bracelet, and the box advertises “Guaranteed Deportation” instead.)

In 2001, Nikas himself remixed a canonical calavera, La Calavera de Don Quixote, along with the artists Art Hazelwood and Marsha Shaw. In the original, a calavera Don Quixote on an equally bony horse charges through a crowd of smaller skeletons, knocking them left and right. Nikas, Hazelwood and Shaw’s 2011 version was made during Occupy Wall Street. In it, the Quixote skeleton trails a banner reading “We are the 99%,” and the tossed-around victims bear the names of various major banks.

“We are the 99 percent, and we are laying havoc to this 1 percent that control so much of the wealth in the country,” Nikas explains, saying they chose this particular image for its freneticism. Nearly a century after it was first made, the calavera remains visually identical, its message smoothly swapped out for a more contemporary one. It jumps entire genres with equal efficacy—La Calavera de Don Quixote also shows up on the label for Espolon Tequila Blanca, this time riding a giant chicken. There, it’s not political art at all, but branding.

What accounts for this boundary-crossing appeal? David Lozeau, a U.S.-based painter who combines calavera imagery with motifs from other cultures, thinks it has something to do with the fact that the calaveras are specific enough to spark recognition, but general enough that they don’t really offend. “They’re so cheeky,” he says. “He [could] do things with skulls that you can’t with people.” Jazmin Velasco-Moore, an artist working in the U.K., calls his style “endearing and clever.” Although she avoids depicting skeletons herself, she says she is particularly inspired by his bold, strong compositions and his limited color palette.

In America, as Day of the Dead becomes more widely celebrated, “everyone knows the traditional image of ’La Catrina,’ but [many] don’t know it’s [Posada],” let alone its original meaning, says Lozeau, who points out that folk artists and non-Europeans tend to get short shrift in the United States. In Mexico, it is the opposite situation: “Posada is everywhere, omnipresent, like God,” says Velasco-Moore. “We grow up with [him] in our subconsciousness.”

In both of these cases, the man has been overtaken by the art. Because his images have been used so many times, Nikas says, “we’ll never really know Posada’s real [political] leanings.” As Durán puts it, “he became a myth.” But his work transcends these concerns—it wears all different skins by wearing no skin at all. “We all have a skeleton inside of us,” Nikas says. “So we can all relate.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook