Timbuktu Is Just a Postcard Away

Years of political unrest have halted tourism in the Malian city, so local guides are bringing Timbuktu to the world—through the mail.

Timbuktu, for many, evokes images of sand dunes and men in robes—a mysterious, illusory place. On the edge of the Sahara Desert, the city served as a center of trade and Islamic learning in the 15th and 16th centuries before entering a period of decline after being captured by Morocco in 1591. In time, it gained its reputation as far-off and inaccessible. By the turn of the 21st century, this was mostly legend—tourists flocked to Timbuktu for the Festival in the Desert every year, and the city was a highlight for the hundreds of thousands of tourists who visited Mali annually.

But in 2012 the city was ensnared in the Islamist takeover of northern Mali. Though the French army intervened in 2013, conflict continues, and insecurity and violence have only become more widespread. Over the last decade, the age-old myth has come true: Timbuktu is a town one can only dream of visiting. Many Timbuktu residents themselves have fled and others don’t dare to take the road between Mali’s capital and the fabled city, a stretch of which is controlled by jihadists. A trip to Timbuktu as a tourist now would be, as Ali Nialy, a former tour guide from Timbuktu put it, “impossible.”

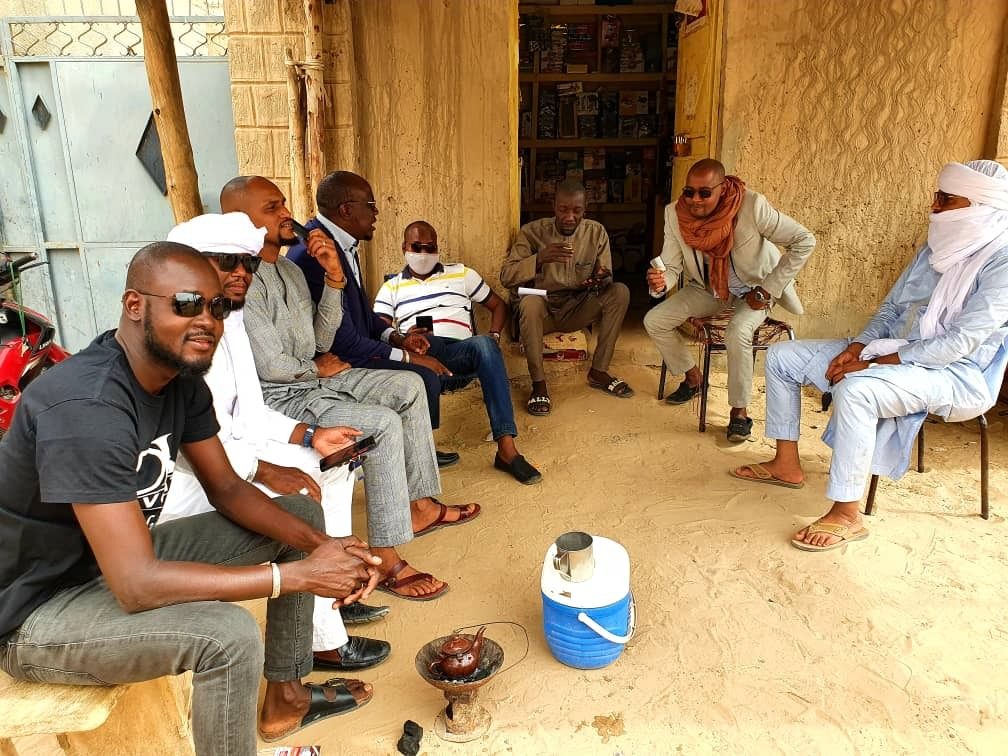

Nialy is part of a team of former tour guides and couriers who make up Postcards from Timbuktu, a project that Nialy and Phil Paoletta, an American hostel owner, started together in 2016. The idea was to give people a chance to send a postcard from one of the farthest ends of the earth to wherever they choose. Postcards have been sent to welcome a new baby into the world, to resolve old disputes with estranged family members, and to profess love: “I love you to Timbuktu and back.” Each is stamped at the Timbuktu post office before passing through the belly of a UN plane, a pack on a courier’s motorbike, and finally the Bamako post office, on a journey that is at the whim of the latest developments in Mali’s ever-evolving crisis.

In 2016, Paoletta received a postcard from a friend back home in the U.S. It was the first piece of mail he had received in his six years of living in Mali, and it reminded him of the joy of receiving a letter. Postcards from Timbuktu was a way to make some income for the guides in Timbuktu who had their livelihoods abruptly taken away a few years earlier.

Nialy was one of them. During the Islamist takeover of Timbuktu, he fled with his family to Bamako. They returned after the liberation in 2013. “I cried a lot. I saw a lot of changes; I saw a lot of things that were destroyed. I didn’t see the same image of Timbuktu that I left. The people of Timbuktu weren’t there. I was walking alone in the street,” he says.

The events of 2012 set off Mali’s ongoing decade-long conflict, or what many in the country refer to in French simply as “les problèmes.” As years passed, insecurity moved further south. Official jihadist rule was over, but to this day control of large areas outside of big cities escapes the state.

Bamako has seen its fair share of unrest, too. In 2020, young people began protesting Mali’s mostly French-aligned government on the streets of the city. The protests were large and frequent, and state security forces shot and killed dozens of young Malians in July of 2020. The state’s violent response to the July protests set the stage for the August 2020 coup d’état. An interim president and prime minister were installed before being arrested in May of 2021, and Mali has been under military rule since.

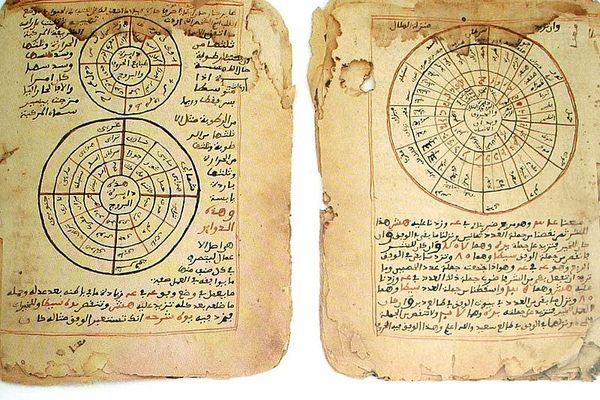

It’s in Bamako that you’ll find one of the last vestiges of perhaps Timbuktu’s most famous and prized piece of history–the Timbuktu manuscripts. A collection of poems and writings on astronomy, law, and religion from the city’s golden age, written and copied by skilled calligraphers. Mali’s last master calligrapher, Boubacar Sadeck, lives in Bamako too. He now creates personalized calligraphy cards for Postcards from Timbuktu in a sparsely furnished room that holds his workshop and some of these manuscripts, which his family has passed down for generations.

Much of Sadeck’s income in Timbuktu came from tourists who took part in his calligraphy workshops. Not knowing how the jihadists would react to his calligraphy, which includes poems and stories that extremists might consider un-Islamic, Sadeck shut his workshop and hid his materials. “All my calligraphy things, I put them in a case. I was afraid to take these on the road. So I negotiated with a truck driver, and he hid my things under his seat. This is how they arrived in Bamako,” he says.

The political situation remains fraught. In December, Mali’s military government announced it would delay elections until 2026 and nine years after receiving a warm welcome in newly liberated Timbuktu, France announced its troops would be leaving Mali.

Meanwhile, prices on food staples have been rising since last year, fuel prices have increased, and sanctions imposed by a bloc of West African countries in response to the delayed elections and backed by France have to a certain degree cut landlocked Mali off from its neighbors. Sadeck says he can no longer source the glass he uses to frame his calligraphy works, and for a time, Air France flights to Bamako were suspended, temporarily preventing mail—including postcards—from leaving the country.

A postcard’s journey begins in Timbuktu, where Nialy and his team of guides transcribe the messages and bring the cards to the post office to be stamped. Then they are put in the luggage of a UN flight bound for Bamako. This is not the Mali postal service’s official route: with all the insecurity between Timbuktu to Bamako, the post office workers advised the team that it was the surest way to get the postcards to the capital.

After arriving in Bamako, the postcards are picked up from the airport and transferred to The Sleeping Camel, Paoletta’s hostel, so he can confirm the addresses. Paoletta is part owner of the hostel, whose clientele pre-2012 was almost entirely made up of tourists. He says they barely pass through anymore, and thus far in 2022 he hasn’t had a single tourist visit.

Then the postcards are taken by motorbike to the Bamako post office, where they leave Mali for good, and their fate is out of the team’s hands.

At the post office, Amara Diarra, unofficial assistant, smiles often. He refuses to speak on anything without adding an optimistic note at the end, usually in the form of “mais, ça va,” implying in French that, well, everything is okay. But of the troubles that sanctions have brought to Malians, he says candidly, “it was a little…catastrophic.”

This can be felt around the country, and Timbuktu is no exception. Nialy says rising prices along with the slowdown of postcard orders after the stoppage of mail have made things difficult. For the time being, he’s taken per diem work as a construction worker.

In his workshop, Sadeck laments the struggles he’s faced in Bamako in recent months. “We’ve asked the landlord to be patient. This month we can’t pay. The economy is bad. Everything is expensive. Food is expensive, oil is expensive, everything.”

He speaks longingly of his time in Timbuktu, boasting that there were dozens of visitors to his workshop every day, with tourists waiting in line to enter the small space. Coming back to present day Bamako, he says all he wants is some return to normalcy.

This is his message from Mali: “If there is a problem in a city, everyone feels it. If there’s peace, everyone feels that, too…everyone is happy, everyone goes out as they like, because they can feel that peace is here. We just want peace.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook