Why an English Museum Has a Collection of Magic Potatoes

Touch of the rheumatiz? Try carrying around a purloined spud.

Rheumatism, the historical catch-all term for a number of inflammatory joint and muscle conditions, is a painful diagnosis. Before the advent of painkillers and the specialized field of rheumatology, there was little sufferers could do. So many people turned to magic, superstition, and folks remedies to ease their pain. Many of them turned to potatoes.

According to this British and American tradition, sufferers of joint pain could simply slip uncooked spuds into their pockets. This would ease aches, it was said, so long as the potato remained in place. The Victorian-era cure had a critical caveat, though: The potato had to have been stolen.

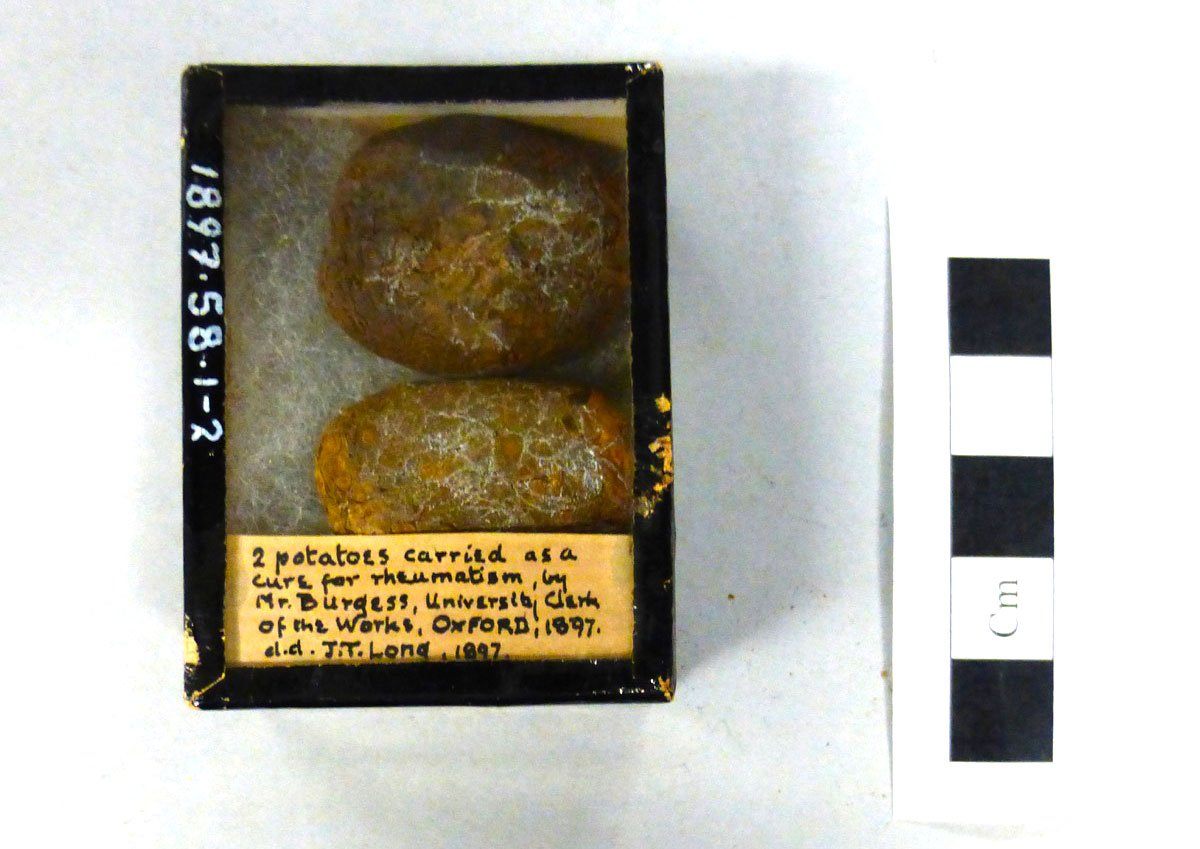

Desperate sufferers ill-got their potatoes in myriad ways. In the countryside, people illicitly dug up potatoes from fields. In cities, they distracted greengrocers to slip away a spud. Often, these potatoes were carried in specially made bags or pockets, and people hauled them for years as the tubers “absorbed” the rheumatism. “It was expected that as the potato shrank the pains would diminish,” one chronicler in 1896 noted in the scholarly journal Notes and Queries.

There’s little use in modern medicine for magical stolen potatoes, but some of the originals still exist. According to Dan Hicks, who specializes in contemporary archaeology at the University of Oxford, the university’s Pitt Rivers Museum has a varied collection of shrunken, withered, therapeutic potatoes as part of its extensive folkloric holdings. Many of the potatoes were acquired at the end of the 19th century, as scholarly interest in both local and global folklore grew. One of them was donated by a Mr. Henry Lister, who had carried it for more than eight years—along with three other potatoes. The practice was an example, Hicks says, of how “people sought to cure themselves of everyday ailments.”

Contemporary observers have been baffled about the origin of the potato charm, but there are theories. Folk tale collector Andrew Lang posited that the potato could be a stand-in for mandrake root, a lauded curative that is also in the nightshade family. Others pointed out that the belief couldn’t be all that old in England, since potatoes were a relatively recent transplant to Europe from the Americas. Accounts exist in the United States as well. One convert to the potato cure, a Commodore Phillips, pilfered a potato from a barrel in Charleston, South Carolina, and defied a doctor who told him it couldn’t possibly bring him any pain relief. An 1897 medical journal quoted him: “I do not believe in it, but I have a potato and I have no rheumatism.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook