The Singular Queerness of Old Coney Island

Drag kings, queer burlesque, and bathhouses abounded.

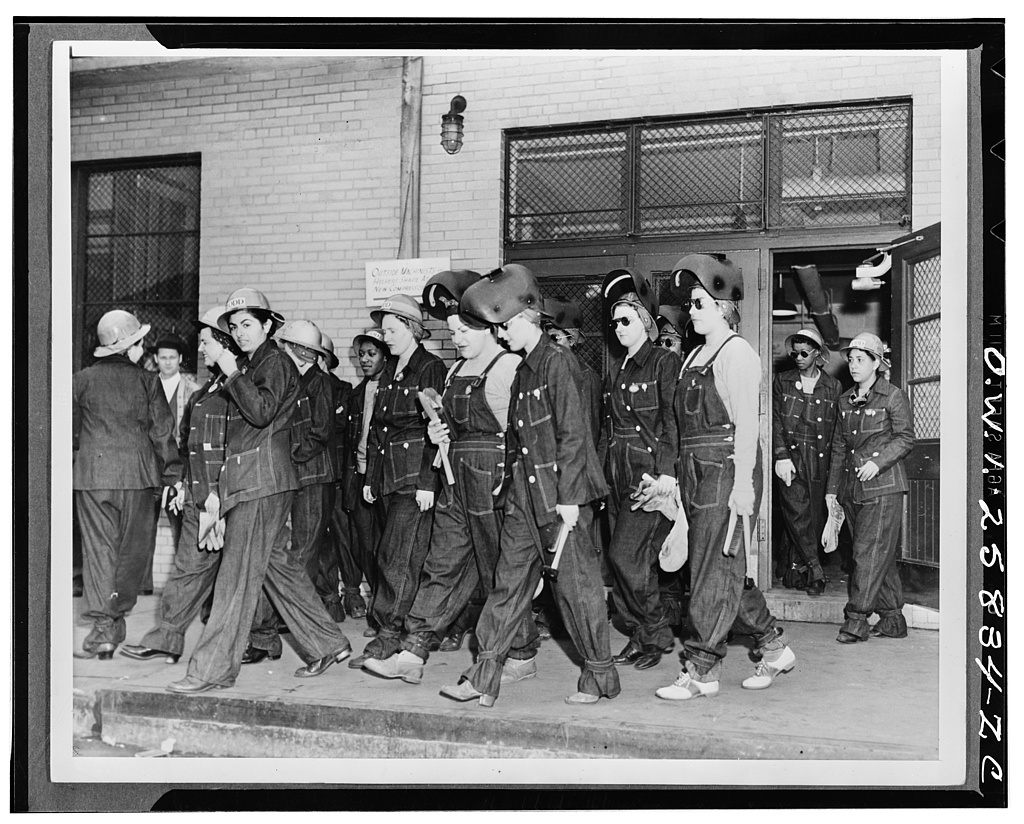

When World War II ended, Rusty Brown knew she was fired. She had been working as a machinist at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, a job that she liked and felt comfortable doing. But with the war effort winding down, the Navy Yard would soon cut 65,000 workers, with no clear alternative employment for the women who’d been hired to do jobs previously held by men now home from war. So Brown, who identified as a butch lesbian, used her grandfather’s name and ID, disguised herself as a boy, and got another factory job to support herself. Brown passed so well as a boy that she realized she could parlay this talent into something a little more lucrative. So she went to one of the only places in Brooklyn where she knew she could perform as a drag king: Coney Island.

To most, the prevailing narrative of queer history in 20th-century New York exists in Manhattan. Decades of private anger and repression culminated in a tipping point on June 28, 1969, when the explosive Stonewall Riots made a stab at some kind of liberation. Manhattan was known for its thriving populations of urban gay men, documented by the historian George Chauncey in 1994’s Gay New York. This is the limited geography the historian Hugh Ryan had always known as the queer history of New York, until one day, he wondered, what about Brooklyn? “Either there is a history that has not been recorded in a way that I’m able to find it, or gay people are like vampires and we can’t cross moving water and therefore we’re stuck in Manhattan,” Ryan said in an interview with the New York Public Library. After trying in vain to acquire a book on the queer history of Brooklyn, Ryan realized he needed to write one himself.

Ryan’s five-year research project began as The Pop-Up Museum of Queer History, a traveling museum celebrating the lives of historical queer people in various cities across America. Eventually, the project came to Brooklyn, and in March 2019, Ryan published When Brooklyn Was Queer. In the early 20th century, many residents of Manhattan were seen as sophisticated and urban, whereas Brooklyn abounded with working-class people. While the documented queer life of Manhattan happened in apartments, speakeasies, and at drag balls, Ryan learned the queer history of Brooklyn took place along the borough’s waterfronts, a space where, thanks to a high volume of commercial activity, strangers often came to congregate in relative anonymity for the day before disappearing back to their private homes. One of the most prominent of these spaces was Coney Island.

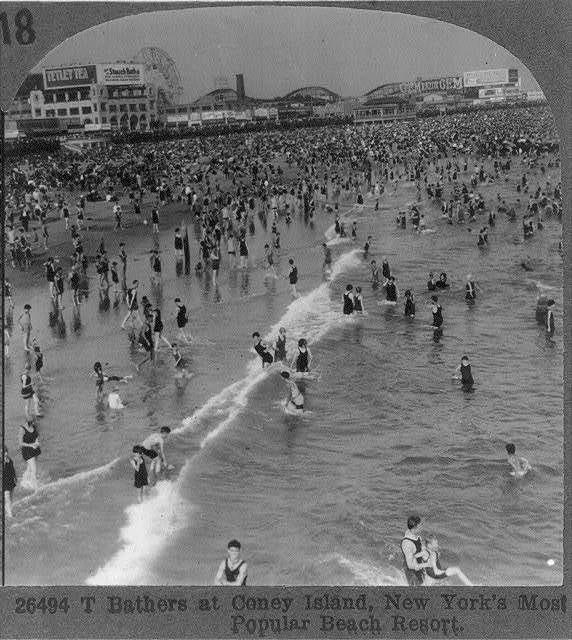

In the mid-1800s, Coney Island was a place for the wealthy. But in 1920, the MTA lowered the price of a subway ride to Coney Island from ten cents to five, giving the neighborhood its famous nickname, the “nickel empire.” Suddenly, anyone could visit Coney Island. By its very nature—so far removed from the city and brimming with scantily clad adults—Coney Island possessed a distinct atmosphere charged with sex, an ambience that helped many people explore their queer desires, Ryan says. “You have this place steeped in sexuality and gender play, and then you pack a third of the population of New York City in it.”

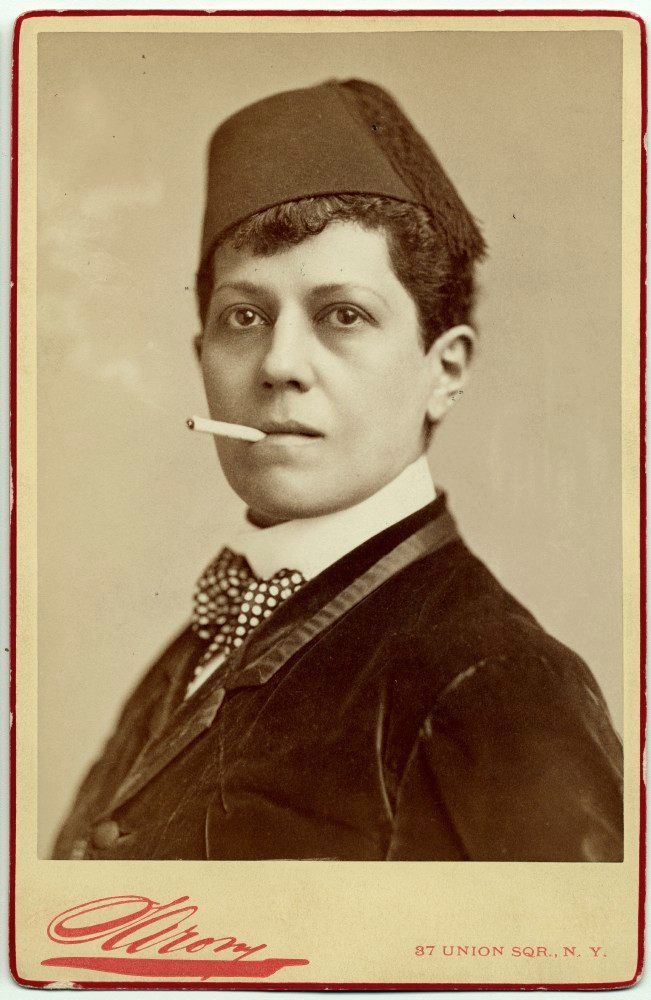

Coney Island’s early affiliation with the circus also made it somewhat queer by design. The boardwalk hosted a number of freak shows spotlighting people who were born outside the confines of an acceptable heterosexual body. There were gender-nonconforming people, intersex people, and people who explicitly played with gender in their acts, including those who claimed to be half-woman, half-man.

Among the most common performers were the bearded ladies, both celebrated and exploited. Bearded women of color were often branded by freak shows as “missing links,” in a racist reference to Darwin’s “missing link” between the evolution of humans and apes. According to Ryan, many performers who played with gender, such as the bearded ladies, were not queer and did not see themselves as connected to queer people. But their rejection of traditional gender norms created a space where queerness was made possible, he says.

But Coney Island’s arsenal entertainment was far from confined to the circus. There was also vaudeville and burlesque. As a newly minted drag king, Brown made the most of the new stage on the Coney Island strip. Though Brown performed what we would now call drag, back then it was called male or female impersonation, the latter term strongly implying it was just a costume, not a latent expression of another gender identity. Brown performed a show that parodied Ginger Rogers and Fred Astaire, with Brown playing the part of Astaire. In the midst of this particularly queer line of work, she happened to spot her soulmate. Brown was sitting in the front row of Madam Tirza’s Wine Bath, a burlesque show where a performer took a shower in 40 gallons of what appeared to be wine, when she spotted a dancer named Terry, who Brown assumed must have been straight. But Terry noticed Brown, too. The two would remain together for 28 years, until Terry died.

Madam Tirza—the stage name of one Leona Duval—was another local queer celebrity on Coney Island. Tirza’s burlesque act consisted of her dancing in pasties under a fountain of water dyed red to look like wine, before a panel of mirrors that multiplied her form. To maintain her custom wine-showering contraption and take it on the road, Tirza got her license as a union plumber and a trucker. She was a known bisexual. Dancers in her show frequently referred to her as a “he-she,” a term that was then often used to describe someone who dated both men and women.

In 1906, a doctor met with a 24-year-old sex worker named Loop-the-Loop, who arrived clad in petticoats and a wide hat fastened with gaudy red flowers, according to an issue of the American Journal of Urology and Sexology. Loop, who was assigned male at birth, called themselves a “fairy” (the word “transgender” would not appear until the last quarter of the 20th century). Loop named themselves after the popular ride at Coney Island, a dual-tracked steel roller coaster that operated from 1901 to 1910.

In his research, Ryan found little public record of queer women living in Brooklyn—though they certainly did—until the writer and illustrator Mary Hallock Foote moved to Brooklyn Heights in the 1860s. Similarly, queer people of color do not enter the historical record until the 1890s. From the mid-1800s until around 1940, Brooklyn was over 97 percent white. So while Coney Island was a queer space, it was a decidedly white queer space.

But some queer people of color managed to make a name for themselves on the beachfront. In the early 1920s, a lesbian named Mabel Hampton began her career as a Coney Island performer in an all-black female ensemble. Only in this troupe did Hampton learn of the word “lesbian,” Ryan writes. “There was one woman in Coney Island—I can’t right now recall her name—but she was the beginning of me being a lesbian,” Hampton said in an interview in 1979. Hampton soon left the stages of Coney Island to grander theaters in Harlem, where she became acquainted with prominent black queer women, including the entertainer Gladys Bentley, the singer Ethel Waters, and the heiress A’Lelia Walker.* In 1985, Hampton was named Grand Marshall of the city’s pride parade. She would go on to become a member of the Lesbian Herstory Archives, a mini-museum in a home on the Upper West Side that can still be visited today.**

Another of Coney Island’s queer hotspots were its bathhouses, particularly the Washington Baths and Stauch’s. At the time, it was illegal to wear a bathing suit on the streets of New York, and most people rented their suits from the bathhouses. So everyone changed clothes in the same place. “There were men naked with other men and women naked with other women,” Ryan says. “And anywhere you create those spaces, you see queer sex.” In 1929, Coney Island held an all-male beauty pageant. “The bathhouse and the judges were shocked when only gay guys showed up,” Ryan says. “But the people who came to watch the pageant were pleasantly surprised.”

There are some clear reasons why Brooklyn’s waterfront accommodated certain kinds of queer life. As Ryan discovered, queer life during this time could flourish only where queer people could have jobs. Life around the docks ran on the shipping business, which ran on sailors who, in turn, relied on the services of sex workers and entertainers, jobs accessible to queer people.

In 1942, Brooklyn Navy Yard began hiring women to work in industrial jobs, such as the one held by Brown before her stint in drag. Anne Moses was the first woman hired to work as a welder by the Todd Shipyards in Red Hook, where she welded twenty-two-gauge galvanized steel to repair aircraft carriers weighing over 20,000 tons. Moses kept a scrapbook of her years working during the war that document a tight-knit group of butch-appearing women, hair shorn short with high-cut trousers and collared shirts. On their days off, the women would go to Coney Island.

But at the end of World War II, Coney Island and the rest of Brooklyn’s waterfront lost the value they once held for the American military. Butch welders like Anne Moses lost their jobs to the many male soldiers returning from war, and the already motley queer communities splintered as these neighborhoods sunk into economic instability.

Coney Island’s queer culture ultimately crumbled in the hands of Robert Moses (not related to Anne). The public official who became well-known as the “master builder” of much of 20th-century New York City, Moses had a very different vision for Coney Island, one with far less amusement. “Such beaches as the Rockaways and those on Long Island and Coney Island lend themselves to summer exploitation, to honky-tonk catchpenny amusement resorts, shacks built without reference to health, sanitation, safety and decent living,” Moses once wrote in a report to the Rockaway Chamber of Commerce, as recounted in Lawrence and Carol P. Kaplan’s Between Ocean and City: The Transformation of Rockaway, New York.

Moses took advantage of slum-clearance laws to seize shops and land at Coney Island, and then kept them empty, effectively driving people away from the boardwalk. He also rezoned the surrounding land for residential public housing and built overpasses too low for city buses to trespass, ensuring only people who owned cars could make their way to these spaces. In the first half of 1946, over 6,000 people were ticketed for crimes that included “ball-playing,” “peddling,” and “undressing on the beach.” Inspectors shut down the bathhouses on sanitary citations. “There was one free municipal bathhouse, used by 150,000 people,” Ryan says, referring to McLochlin’s baths. “And Moses turned it into equipment storage for the parks.” As businesses disappeared and visitors came less often, crime skyrocketed. Soon, the “nickel empire” became the “Devil’s playpen.”

Coney Island’s stalwart but scrappy queer communities buckled under this new municipal pressure. In 1952, the License Commission shut down Madame Tirza’s show. Too afraid to reopen, Tirza married a man from Coney Island named Joe Boston and they struck out on the road. In 1949, someone with the pen name Swasarnt Nerf published “The Gay Girl’s Guide” to New York and only included two places in Brooklyn, noting Coney Island as a place of last resort for a beach party. “All the queer narratives in the 1950s said the same thing: ‘Coney Island is dead. You can no longer be queer and go there,’” Ryan said.

In the 21st century, Brooklyn has reclaimed its past and is queerer than ever, with queens defining the future of drag and LGBTQ+ chefs cooking soup to foster community. Each June, the Coney Island Mermaid Parade pays homage to the neighborhood’s queer, kitschy, and costumed past. But Ryan hopes his work will help 21st-century queer people living in Brooklyn, on the waterfront or elsewhere, reconnect with their forebearers who hooked up in bathhouses and welded airplanes before Stonewall. The next time you’re in Coney Island, pour some wine—or wine-colored water—out for Madam Tirza.

* Correction: This story was updated to make it clearer that A’Lelia Walker was not herself a performer.

** Correction: The story was also updated to make it clear that Mabel Hampton was not a founding member of the Lesbian Herstory Archives.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook