In Buenos Aires, Queer Tango Takes a Revolutionary Dance Back to Its Roots

In traditional tango, men lead and women follow. Queer tango is creating a new paradigm.

Two decades ago, when Mariana Docampo was in her twenties, she went looking for somewhere she could dance tango with another woman. Buenos Aires, where she lived, was a dance capital and the home of countless milongas, or gatherings of Argentinian tango dancers. But as she learned to dance the leading role, she realized that she was looking for something that didn’t exist. “I had loved tango from the first time I discovered it, but milongas were a place you could go only if you played a certain role and certain identity,” she says. “That was the beginning.”

For many, the word “tango” comes with certain expectations: charming men dancing with women in high heels, tables ordered around a dimly-lit dance floor, wine bottles over here, candles over there. That classic milonga, which developed around the turn of the 20th century, has not changed much in a hundred years. But in recent years, queer milongas have slowly transformed the roles and dress codes of traditional tango.

In 2001, a group of German dancers organized a Queer Tango Festival in Hamburg, and Argentina was quick to follow. In Buenos Aires, Augusto Balizano founded the first gay milonga, La Marshàll. In 2005, Docampo opened Argentina’s first permanent lesbian milonga: Tango Queer. These milongas aimed to serve specific communities, but were open to people of all genders, and have broadened their aims over time.

In the years that followed, the Argentinian government passed laws that enshrined the civil rights of LGBTQ people, from marriage equality to gender expression. “Queer dancing was a social need,” says Balizano, an internationally known tango dancer who has performed in Germany, France, Denmark and even Russia, which is not known for LGBTQ rights. “When La Marshàll started, it was revolutionary, and existed long before those laws, so I think the fact spaces like ours existed was a big contribution.” Together, Docampo and Balizano founded the International Queer Tango Festival, an annual event that is now in its 14th year, and that attracts dancers from all over the world.

Sofìa Ceccioni, a sociologist at the University of Buenos Aires, has researched how queer tango is challenging old power structures. In a 2009 paper called “Tango Queer: Territory and Performances,” Ceccioni argued that classic tango conceived “the masculine as the active, the dynamic,” while the feminine “was associated with the passive and sacrificed.” The leading role reserved for men, the author went on, expresses a “socially passive position” for women. Queer tango has the power to move past this binary framework.

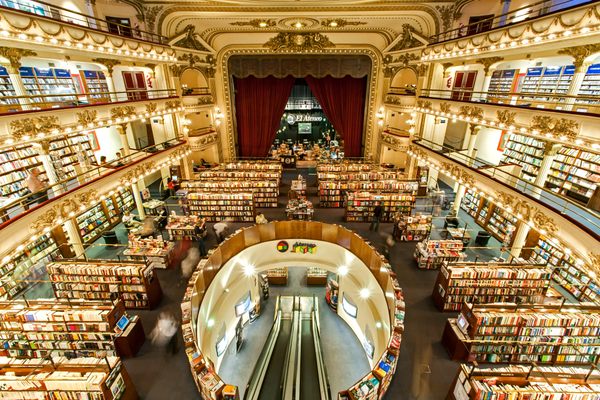

When she first stepped into tango, the singer Fifí Real did not expect to find a fully accepting space for her music. After the passage of Argentina’s civil rights laws, she exercised her right to affirm her gender identity on her government ID card. Since then, she has performed across the city, in spaces such as Tango Queer and the Maipo, one of the most glamorous theaters in the city. “For maricas, it was necessary to access traditional and popular music and tell our stories and realities there,” explains the 32-year-old artist, using a Spanish word for “queer” that was once derogatory, but has been reclaimed by LGBTQ communities. “I understood we could enter our popular music through tango, and that was critical for us.”

Milongas are always about more than just dance, and queer milongas are no different. “Many couples were formed here, many broke up,” Balizano says. “I found a partner in La Marshàll, and we broke up because of La Marshàll too! Our anniversaries are very touching.” The dance floor of Tango Queer was also a setting for romance. “We have had a lot of couples that ended in marriages,” Docampo says. “Some even came to marry at the milonga! There was a guy who asked for the other’s hand in front of all the people.”

Tango first emerged on the outskirts of the city, as the perfect poetic and musical medium for the outcast and marginalized to tell their stories. With this in mind, perhaps queer tango is just a new way of living up to the dance’s traditional roots. “The fact that we had shown we existed made many people understand: Tango cannot be conceived in a single way,” says Balizano. “In my opinion, this is the last great revolution made by tango.”

Recently, a 27-year-old tango lover named Martina Berardi tried to explain what the queer milonga La Furiosa means for her. “There’s no other place where I can feel what I feel when I dance here. It is like being myself, but being it in such a beautiful way,” she says. “Tango is a passion you could only understand when dancing, and dancing it in full freedom is a way of reaching the best expression of myself.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook