The Extremely Enchanting, Totally Perplexing, Possibly Never-Ending Quest for the Golden Owl

For 30 years, this labyrinthine treasure hunt has had thousands of players cracking codes and digging up the French countryside. After a sudden death and bitter disputes, will the prize ever be found?

(Update: The owl has been found, according to BBC, CNN, and other news outlets. While the location was not disclosed, official owl channels confirmed it was unearthed on Oct. 3.)

This story was originally published on Narratively. Subscribe to their newsletter here.

Months after he buried it in darkness, Régis Hauser still dreamt of “the beast.” Of the hole he dug at 3:30 a.m. on April 24, 1993, three feet deep somewhere in France. How he lugged the hunk of metal from his car trunk and placed it in the dirt. When he told his tale to the French newspaper Libération, he made the entombment sound faintly gothic: “I hadn’t even finished, and my hands were bloody. When it was done, I went far away, to get breakfast. I looked at myself in the mirror at the cafe. I was barely recognizable, disheveled, covered in earth.” No one had seen him in the act, or so Hauser hoped. Years later, he recounted seeing just one person during his whole expedition: a dog walker looking for his animal. How could he forget the hound’s name: Dracula.

The object Hauser buried that night was a bronze sculpture of an owl. He had promised that whoever found it could exchange it for an identical owl cast in gold, silver, onyx, diamonds, and rubies, worth about one million francs (around €235,000, or $257,000 today, adjusted for inflation). Its location could be divined by solving 11 puzzles, a combination of riddles and illustrations, published shortly afterward in a book he wrote called On the Trail of the Golden Owl.

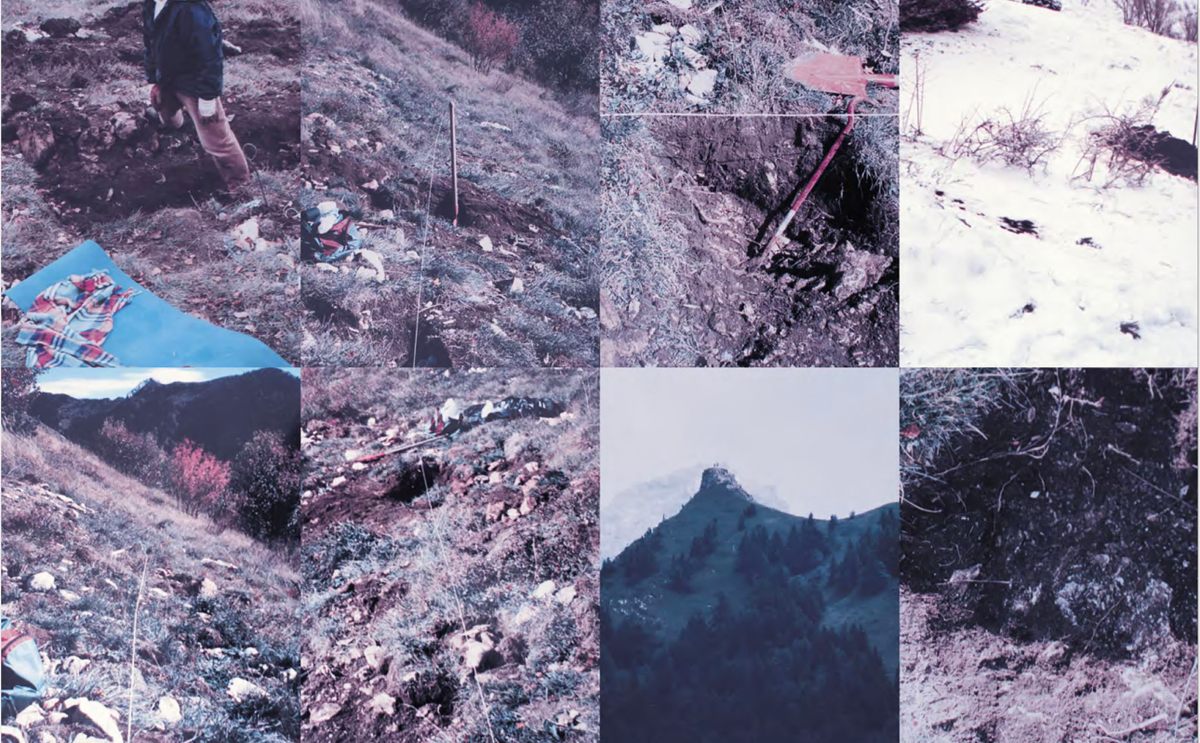

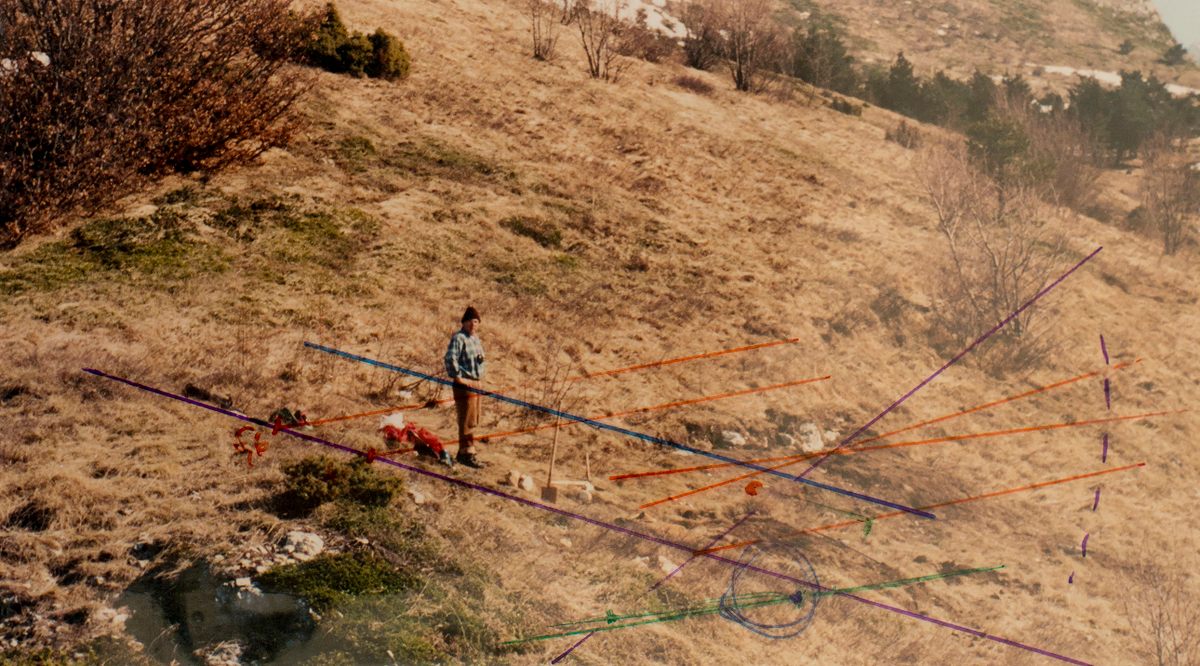

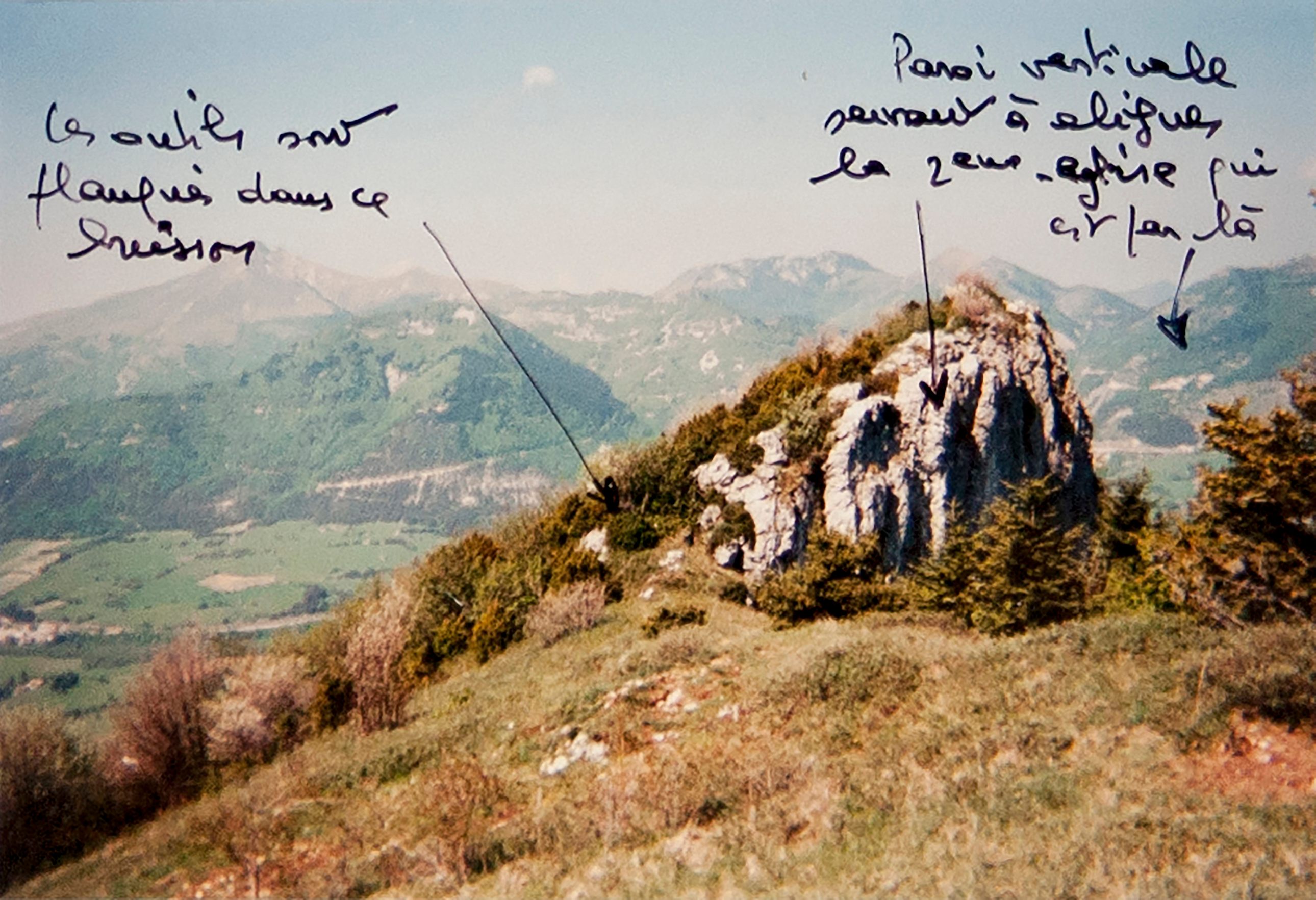

Nearly 30 years later, the artist who conceived of both birds, Michel Becker, hacked at the dirt on the same spot where Hauser had buried it. With thousands of people still searching in what is now the world’s longest completely unsolved armchair treasure hunt, Becker wanted to assure everyone it was still locatable and intact. He had been digging for nearly three hours when his pickax chinked on metal; he dropped to his knees and gouged soil with his bare hands. “I knew my owl, its dimensions, its weight, and I started scraping around what I thought was the edge of a wing. I was on an emotional rollercoaster.” But when he pulled off its plastic shroud, he swore loudly: It was just a tawdry rusted metal bird, not his beautiful owl.

What had happened? It was October 2021, and Hauser couldn’t tell him; he had died 12 years earlier. “Walking with rage-filled steps, I muttered, grumbled and fulminated inside, vowing to drag [Hauser] off to the stocks.” The trail, and his collaborator’s tale, had spun him around in circles.

Three decades after the owl was first buried, Michel Becker is riding high again in April 2023. A checked flat cap on his head, an ashtray overflowing with butts at his elbow on the bar, he greets every one of a long line of acolytes with a delighted grin. These are the chouetteurs (owl hunters), and this is the Festi’Chouette, the 30th anniversary celebration of the hunt he co-created, in the town of Rochefort in western France. We are in the high-vaulted spaces of the Lingot d’Art, a former 19th-century water tower Becker has converted into an upscale bar and museum devoted to treasure hunting, where the golden owl prize is held. The atmosphere is festive: People are racking up pints, tinkling on the piano, speculating about where in France the golden owl’s bronze twin could be hiding—less a parliament of chouetteurs than a hoot.

Becker finally acquired the solutions to the 11 puzzles at the start of 2021 from the late Régis Hauser’s family. Never privy to them before, even though he had created the hunt’s visual identity, he was from that moment on, finally its gamemaster. After verifying the cache site, he relaunched the book On the Trail of the Golden Owl from a publishing company he set up. The race to solve the riddles and find the owl is still on—the big rumor is that he is going to hand out an additional clue tonight. “Only on the condition that you dance later!” he says to the crowd.

At the start of the weekend, the first arrivals convene in a ring of garden chairs outside a bar-tabac opposite the water tower. “So you’re Exalastro!” “Oxymore!” “Palestrina!” Most have never met before; they’re hailing each other by the handles they use on the On the Trail of the Chouette d’Or channel on the social platform Discord, where they have been discussing the puzzles since Becker took over the game.

The majority are members of AOC (Association Officielle de Chouetteurs), a club set up a little more than a year ago by associates of Becker to rival A2CO (Association des Chercheurs de la Chouette d’Or), the original organization established in 2003 on the game’s 10th anniversary.

“Protestant versus Catholic—that’s where we’re at,” says Palestrina, a sharp-eyed 39-year-old from Arras. “All religions follow God, but not in the same way,” observes Gringos, 40, apparently AOC’s resident jester.

The general consensus here among the AOC faithful is that Michel Becker—who replaced the rusted substitute with a second bronze replica of the owl when he checked the cache in October 2021—has put the hunt on the correct course once again. “The fact that he verified the cache with a sworn-in bailiff changes everything,” says Largo, a chouetteur from Bordeaux, cradling a glass of La Chouffe beer. (French huissiers, or bailiffs, are legal officials mandated to execute court orders and establish due process. Becker hired his own bailiff, who took over from the multiple sets of bailiffs originally charged with overseeing the game.) “We know it’s there and that it can be found.”

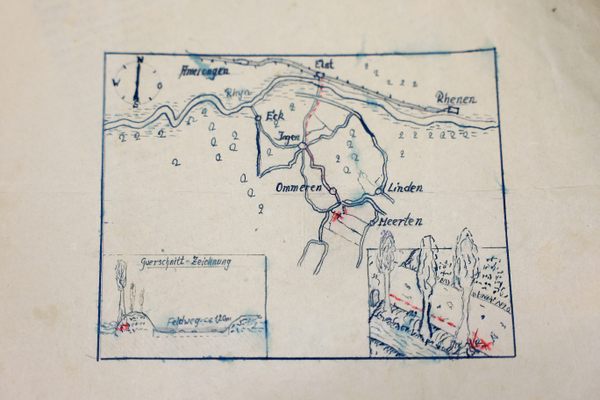

Hang around with some chouetteurs for longer than 10 seconds, and snatches of arcane lexicon fill the air: “le Mega,” (short for mega-astuce, or super-solution) “la flèche d’Apollon” (Apollo’s arrow), le “NNP” (navire noir perché, or perching black ship). Such is the terminology of the 11 puzzles written by Régis Hauser that, in tandem with Becker’s illustrations, pinpoint the dig site; a Dan Brown–esque compendium of word games, mathematical ciphers, historical allusions, cartographical exegesis and plain old mindfuckery.

The first few have definitively been solved, and thereafter the treasure hunters quickly disagree about almost everything (including about at which point in the puzzles they start disagreeing). One particularly important schism in the community is whether you are “daboist” or “anti-daboist,” depending on whether you insist that Dabo—a village near the border with Germany—is a key locus for the game, even perhaps the dig zone. This has a certain emotional logic, given that Hauser was born a few dozen kilometers to the north.

If you fancy a head start as a chouetteur: The book’s fifth riddle gives the running order of the other 10, which are printed out of sequence. Then, the next riddle is an octet that is a charade spelling out the seven letters of Bourges, the central French city that is the starting point of the hunt. The subsequent puzzles send the chouetteurs identifying different places and triangulating trajectories on the map of France until they have zeroed in on a dig zone where they will go and hunt in the field. The book specified that the owl was buried on public land; Hauser confirmed early on, on a TV panel show, that it was not within 100 kilometers of the French coastline. In 1994, he also revealed the existence of a hidden “super-solution” that incorporated elements of the 11 printed riddles into a key that zeroed in on the exact location of the owl within the zone. He estimated the hunt would be solved between eight and 14 months.

But in Rochefort, 30 years later, the chouetteurs—whetted by the first sips of lager—are still hard at it. Overwhelmingly male (female chouetteuses are a small minority) and predominantly early middle-aged, the throng gives off an almost virile buzz, with everyone trading ideas and solutions. There are around 3,000 active searchers in the Golden Owl hunt—a handful abroad, but predominantly in France—and maybe as many as 200,000 since it started. A fresh influx has come in with Becker’s renewal of the game, but many are hardened veterans.

The treasure hunters come in all character and personality types: lone rangers, organized teams, precise rationalists, visionaries prone to imaginative epiphany. Vehement as everyone is in arguing their particular route through the puzzles, at some point in the discussions a veil of coy silence descends. If the reasoning is sound enough to be worth the bother of digging, then it has to remain confidential. “It’s like mushroom hunters with their secret spots,” Mazibra and MH, a husband-and-wife chouetteur outfit tell me.

At the end of the day, the intellectual reasoning required, and the decision to keep going, are personal concerns. Mblond is a soft-smiling 67-year-old stalwart of the hunt, a member of both AOC and A2CO, who has a way of welcoming you like an old friend. He no longer believes he will be the one to find the owl, though he seems utterly at ease with that. But he warns of a dangerous obsessiveness the hunt can induce. Cattia17, in a blue puffer jacket with a curious Egyptian-style pendant round her neck, can testify to that. She has been involved on and off since the game’s first year in 1993. (She declines to disclose her age, saying, “Between chouetteurs, there are no age differences.”) Her son wants her to stop because he thinks it has become an addiction. In any case, she is out of leads: “I’ve had enough. After 30 years, you start to turn in circles.” She plans to go cold turkey at the end of the month. Plus, it’s an expensive pursuit in the long run: The average weekend field trip can run to several hundred euros. Many eager chouetteurs make multiple trips a year, but there are circumspect veterans who, uncertain of their solutions, have never dug in the field.

On the second day of the Rochefort meetup, the believers get their glimpse of the True Cross. The hallowed golden owl is downstairs in the crypt of the Lingot d’Art, held in safekeeping as one of the exhibits—until someone finds the dig site. At 10 a.m., AOC club secretary Surf—or Sébastien Malkic, a 46-year-old who works at Disneyland Paris—is standing guard outside the entrance to the crypt, letting people down in groups of 15. “I haven’t even seen it yet,” he says. “I want other people to see it first.”

Down in a low-ceilinged sepulchre lined with fake flaming torches is Becker’s “beast”: the golden owl itself, one-foot tall, perched in an alcove on a marble, reliquary-style base.

“Fucking hell!” “Ooh la la!” our group coos. The bird’s wings are aloft like the Winged Victory sculpture, a coruscant gold sweep with an ethereal silvery sheen of miniature diamonds; its quartz eyes are downcast with tristesse. It has the same furtive look, as if it knows it cannot be captured, as the Maltese Falcon. “You can almost touch it,” says Gringos. Our guide quickly reprimands him: “That will set off the lasers, and the police will be here in five minutes.”

Upstairs, people file rowdily around a long space lined with Becker’s original paintings for the illustrations in the Golden Owl book. Five feet or so high, they are far more vibrant in the flesh. “It’s like seeing the Joconde in real life. It’s strange,” says Gringos. There’s an air of the barbarians at the gates of Rome; people seem almost cowed in their presence. Later, Surf is struggling to keep his feelings in check after finally seeing the owl in the flesh: “When I was in front of it, I saw 30 years of my life flash before me. I had to be strong.”

Signing On the Trail of the Golden Owl books for the pilgrims in the evening, Michel Becker is lapping up his moment of triumph. But days earlier, he had confessed that he wasn’t even sure he was going to be there: “The problem is that the chouetteurs can’t control themselves in my presence,” he said. “Which means I’ll get eight hours of nonstop questions.” This explains his often stern, headmasterly way with them on the Discord group audio chats—which sometimes run to several hours (one user could be heard snoring in the background of a recent one). But the 73-year-old Becker is a smooth operator too, stooped, but still with an angular face and pert mouth that are somehow redolent of his abbreviated art style. Mellifluous-voiced, he is a front man who knows how to say all the right things: “The history of the hunt is still being written. But now it’s the chouetteurs who are writing it.”

Becker was already a successful exhibited artist when the Golden Owl project was gestating in the early 1990s. Moving between homes in the south of France, he had a certain aristocratic bearing (he traces his ancestors back to French pretender king Henri d’Artois, the last remaining male heir of the French Bourbon dynasty ousted in the revolution). In L’Isle-sur-la-Sorgue, the Provençal town where he lived, he liked to help the postman deliver the mail in his vintage Rolls-Royce.

The artist was introduced to Régis Hauser by his childhood friend Hervé Schick, a businessman looking to start his own brand of luxury jewelry. Schick had hired the 45-year-old Hauser, a freelance marketing consultant who lived on the outskirts of Paris, for publicity advice; the latter suggested a treasure hunt as a way of building buzz for the jewelry brand. Hauser was inspired by the original “armchair treasure hunt,” Kit Williams’s Masquerade—a 32-page book launched in the United Kingdom in 1979, setting players on a quest to find an 18-carat golden hare. As the game was promoted in part on airlines, Hauser may have encountered it on flights back from the U.K., where he worked as marketing director for cosmetics giant Avon.

Becker’s vaunted heritage provided the inspiration: Clandestine royalist rebels who supported the disinherited monarchy during the French Revolution, the chouans, used the cries of the tawny owl as their call sign. So the treasure became a chouette (owl), despite Hauser’s initial misgivings. “It’s a very negative symbol to some people—the peasantry thought it brought bad fortune when it hooted,” Becker says. “But we pointed out that in other cultures it was a symbol of wisdom, like Athena.”

Then, with puzzles and paintings completed, and the planned burial only weeks away, Schick pulled out. Other deluxe jewelry brands he worked with frowned on the idea of him starting his own line. Becker, eager to continue a project that would publicize his work, wanted to press on—to the point of financing the creation of the golden owl sculpture out of his own pocket. He didn’t know Hauser well enough to speak about his motivations, but the artist recognized his collaborator’s qualities: “He was what I would call a hawker. He was a guy who was, above all, a seller who had a good command of the French language, a good writing technique because he passed his time writing copy for sale by mail. He wanted to sell his stuff.”

There was one snag in the last-minute preparations. Hauser initially wanted to bury the golden owl itself—but Becker and Manya, the book’s publisher, were reluctant to actually put the million-franc treasure underground. In any case, the finished statuette was not ready on April 23, 1993, the planned launch date, and Manya insisted that Hauser bury the bronze copy instead. So, this was what the author put in the ground in the small hours of the 24th, like a furtive corpse dump, or at least that’s the way he recounted it. The 44-page book was published in late May, containing Hauser’s puzzles, Becker’s illustrations and an introductory spiel by the former fluffing up the artist’s chouan heritage to add an additional allure to their creation. The book was credited to Becker and “Max Valentin,” the PI-ish pseudonym Hauser had concocted for himself, pulling the surname out of the phone book. He wanted the cover of anonymity to shield himself from rabid treasure seekers.

This, says Becker, is where the problems started. In the preface to the relaunched 2021 book, he writes: “Solicited constantly by his fans, [he had] become accustomed to the widespread fascination with this character, and to the mystery engendered by his anonymity.” As the game got underway in the mid-1990s, Hauser invested in the fiction of Max Valentin, always hiding his face for TV appearances, and, dialoguing with the players about the riddles, became the omniscient gamemaster. But in doing so, Becker believes, his personality changed: “From then onward, the tone was no longer the same—he became a lot harsher with me.” Questioned about it further, his narrative line is more incendiary: “Régis Hauser manipulated the game from the shadows—and used Max Valentin as cover.”

One night 13 years later, Becker received a phone call from Hauser—in a panic. “Pitiful, melting, he began each of his phrases with: ‘I’ve got nothing to do with this,’ ‘It’s not my fault,’ ‘I don’t understand,’” the artist later wrote.

It was September 2006, and the golden owl had been seized in bankruptcy proceedings against what was the book’s third set of publishers. To be precise, the bird—worth thousands of euros of Becker’s money—had, unbeknown to the artist, been confiscated nearly two years earlier in October 2004. Hauser had been unsuccessfully trying to appeal the decision since. With the prize still in the liquidator’s hands, Hauser was freaking out about the legal viability of the game should someone unearth the bronze copy. He hadn’t wanted to alarm his collaborator before, but now he needed his help. Becker was livid.

Since the start of the hunt, the gold statuette was legally supposed to be held in the vault of a bank outside Paris. Becker claims that he only learned in 2006 that, following the bankruptcy of the book’s first publisher, Manya, in 1994, Hauser had left the owl in the hands of a new publisher, Bonnier-Dora. This may have been as security against the costs of setting up a Minitel server, a French precursor to the internet that Hauser used to answer chouetteurs’ questions. (Surviving Bonnier-Dora staff did not reply to requests for information.) When this publishing agreement broke down in 1997, the owl was stowed in a new location in a bank near the Arc de Triomphe, in a vault rented by a company Hauser set up to co-publish the book’s third edition, which later merged with another company to become a new publisher, In Folio. The owl’s change of location happened again, by Becker’s telling, without his knowledge. Upon finding the safety-box keys in In Folio’s offices after they in turn went under in 2004, the liquidator expropriated the bird.

All this behind-the-scenes improvisation and shoring up was in contrast to the figure of Max Valentin, consummate master of ceremonies. Becker was generally sent out for early TV promotional spots, while “Valentin”—when he appeared—wore a balaclava. But he became the point of liaison with the players, dialoguing with them over Minitel throughout the 1990s.

Hauser would sit on the stairs in his family home in Bois D’Arcy with the Minitel machine on his lap, tapping out messages for hours. Taking 6,000 queries in the first three months alone, he later claimed to have answered nearly 100,000 in total. He was a deft gamesmaster: tantalizing with hints, teasing over the “fausses pistes” (red herrings) he’d set in the puzzles, but always a reassuring omniscient presence. Known as “Madits” (a contraction of Max m’a dit, or “Max told me”), his oracular pronouncements—on the specific puzzles, which maps to use, whether metal detectors were cheating—became a Talmudic annex to be pored over. As the decade wore on and he launched many other parallel hunts, Max Valentin became the affable éminence grise of France’s treasure seekers. His personal mystique only accrued the longer the owl remained underground (all of his other hunts were solved within the year or so time frame originally planned for the Golden Owl hunt).

But this cordial bond with the players was also a source of revenue for Hauser: They paid to use the Minitel, around 500 francs ($80) an hour, according to Becker. (Becker says Hauser took 50 percent of the revenue, against the artist’s 5 percent—though the latter never touched a Minitel keyboard. Becker, meanwhile, enjoyed a more favorable two-thirds share of the royalties, to recognize his financial investment in the owl.)

When they were conceiving the hunt, Becker had been surprised to find that Hauser’s “European marketing operation” consisted of rented premises in a tatty business center in the Paris outskirts: “Clearly he wasn’t rolling in it. He’d obviously seen better days. Had he had professional or financial difficulties? I don’t know. But when we met him, he was addicted to money.” (Chouetteurs close to Hauser dispute this.)

The owl’s movements may indeed have been hasty arrangements in the changeover between publishers, but Becker claims that Hauser certainly duped him in order to secure financial advantages for himself. The artist says that when the agreement was signed with the original stakeholder, Manya, Hauser hadn’t mentioned that he held a 2 percent stake in the company. So Hauser, likely aware of Manya’s financial difficulties, seemed to have steered Becker into signing for a leaky ship, hoping the Golden Owl hunt would bail it out. With Manya sinking financially at the end of 1993, he arranged for the company he part-owned to sign over all exploitation rights for the hunt to him alone.

With Hauser no longer around to defend himself, his family unwilling to talk and Manya’s two key directors now deceased, it is unclear if these arrangements were the result of sloppy business, communication issues, or, as Becker insists, duplicity intentionally designed to sideline him.

As for the changes to the owl’s home and the contractual shifts happening without his consent, Becker simply says: “I was naïve, I trusted [Hauser and Manya]. I was totally deficient on that score.” His lack of oversight seems odd given what he had invested in the sculpture. It came despite the fact that Hauser had phoned him in December 1993 to warn him about Manya’s imminent bankruptcy, even if the author did not fully disclose his tight-knit relationship with the company. Becker’s signature also appears on the contract they signed with the book’s third publisher in 1997, which restituted the rights supposedly hijacked by Hauser back to the publishers.

Then there were the solutions to the puzzles, which were legally supposed to remain in the guard of the same bailiff who also kept the keys to the vault containing the owl. This was in order to guarantee that they hadn’t been tampered with at a later date by the organizers, or seen by anyone inclined to cheating. Pointing to a bailiff’s June 1994 report—which states that Hauser only deposited the rules, not the solutions—Becker speculates that his partner kept sole control of the solutions from the launch of the book’s second edition onward. No one knows why, but his actions compromised the integrity of the game and encouraged suspicions that it could have been altered post-launch.

The owl’s seizure was made public in October 2006 by Elessar, a longtime chouetteur. The gamemaster, in messages on the A2CO forum, said that he kept the situation secret because he thought it would be easy enough to prove that the sculpture was not an In Folio asset. He also hadn’t wanted to disrupt the game.

But the months of deception took their toll on Hauser, according to Monglane, a one-time chouetteur who was also Hauser’s neighbor in Bois d’Arcy. He wrote on his blog: “I can bear witness to the unbearable nervous tension that this dissimulation provoked in him, the duplicity—being contrary to his nature—wracking him with guilt all the while.”

The artist channeled his anger toward Hauser by taking charge of the legal case the writer had already launched to reclaim the bird. His partner had no choice but to allow this—he needed Becker’s financial backing to continue the appeal. The latter was finally reunited with his avian trophy in January 2009. Ruling that the golden owl had never been an In Folio asset, the Versailles court of appeal ordered it returned to the bailiff originally charged with ensuring that the statuette was held in security. But they refused to take it—probably because, with no legal precedent for a prize in a treasure hunt, its ownership had become so controversial. Given their reluctance, the fact that there was no active publisher and no one had found its bronze twin yet, there only seemed one logical choice: The court returned it to Becker. Just as well for the fractious relationship between the collaborators—“Otherwise, it would’ve been war between him and me, that’s for sure,” Becker says.

But they never got to make up. With a puzzle-setter’s precision, the writer died of a heart attack on the 16th anniversary of the game, on April 23, 2009, at age 62. The stress of the initially hush-hush legal case and then three years of hearings may have impacted his health; he was also a heavy smoker who had been undergoing hospital treatment for a pulmonary edema in the months prior.

Hauser’s death was a seismic shock for the chouetteurs, especially those who’d had personal dealings with him. But it must have been unbearably bitter for his wife and two daughters, who were 31 and 21. He had been a workaholic who often slept only five hours a night and calculated that he had worked 4,444 hours in 2000 (averaging over 12 hours a day, seven days a week); not just on his various treasure hunts but also other marketing jobs and a budding writing career. As the hunt, formally known as On the Trail of the Golden Owl, dragged on, it in part deprived them of a husband and father—and then, if it really was the pressure from the trial that caused Hauser’s heart attack, finally robbed them of him completely.

Despite the tragedy, Becker decided, in a May 2009 blog post on a chouetteur forum, that it was the moment to let his feelings be known: “Without the owl, and dare I say it without me … his puzzles would have stayed in the box. That’s why he did everything to push me aside from the game and finished off by thinking he could do whatever he liked with the owl, without asking me. I feel a great sadness knowing he’s gone, but at the same time, I’m frustrated to not have him in front of me, with the trial over, so I can tell him how furious his ‘antics’ made me.”

Do Hauser’s actions add up the Machiavellian “stick-up” Becker claims it to be? You’d have to have an owl on the shoulder of Athena herself to get a clear enough view to judge. The reality is no doubt somewhere between the artist and the writer, with the chouetteurs scrambling around in the middle as usual.

You have to work in three dimensions—it’s obvious!” Geed up by a couple of glasses of genièvre liquor, veteran chouetteur Flytox reckons his calculations are superior. “Most people only think in two dimensions,” he says of the puzzles’ late-stage orientations using large-scale maps. A strapping 60-something who resembles Martin Sheen, he has natural authority in matters of elevation as a retired commercial pilot. “Why stop there,” I ask? “Why not hit up the fourth dimension—time—too?”

“I’m not there yet. But I think when the game ends, the fourth dimension will come into it.” He leans conspiratorially over the dinner table. He’s messing with me. I think.

Two weeks after the shindig at Rochefort, the A2CO annual convention—hosted at a former military hospital near the city of Bourges, the game’s point of departure—is underway. In a high-ceilinged function room, the members weave between the tables, offering around delicacies from their region: suppurating hunks of Roquefort and Saint-Nectaire cheese, truncheon-like saucissons, eau de vies in unmarked bottles.

Nearly 70 in number, the chouetteurs here are on average 20 years older than the AOC crowd, drawn largely from the original generation who picked up the game in the 1990s. A2CO is the Shi’ite faction who cleave to the faith of the original prophet, Hauser, and snub Becker’s new caliphate. The artist’s inopportune broadside after Hauser’s death in 2009 caused widespread rage; his relationship with the A2CO club has never recovered. “I’m the big villain to them,” Becker says.

The Golden Owl had been flying blind between 2009 and 2014, with no gamemaster and the books out of print. Ground down by the court trials, Becker was wound up further by fruitless negotiations with Hauser’s heirs to obtain the solutions to the puzzles and ensure the game’s future. But the talks always petered out. So Becker doubled down in his iconoclasm, making a bombshell announcement on June 2, 2014: The trophy was being put up for auction a fortnight later, he said, effectively bringing On the Trail of the Golden Owl to an abrupt end.

The chouetteurs quickly mobilized, both lobbying auction house Drouot, the Parisian equivalent of Christie’s, to prevent the sale from going ahead, and launching a legal attempt to seize the statue. In the face of the argument that, according to the game’s rules, the statue should have been held in security, the auctioneers quickly ceded and pulled the sale. But A2CO ultimately failed in its bid to wrest the owl from the artist; moving at glacial French legal speed, the Paris court of appeal finally ruled in January 2017 that the statuette was legally Becker’s, at least until its replica was unearthed. Soon after, Becker tried to bring the game under his wing, launching a fourth, partly crowdfunded edition of the book in 2019. But without the solutions until 2021, the game essentially continued leaderless in the interim.

The late gamemaster, meanwhile, is much missed. Several A2CO stalwarts were close to the man they knew as Max Valentin, meeting him socially as well as on the Minitel (always under the condition that they didn’t discuss the Golden Owl hunt during any of these private meetings); he seems to have been a loyal and protective friend. The rare photographs of him show a blond-haired, bearded man with big spectacles and a melancholic, distant expression.

One A2CO member, Mickey, recalls sprawling email exchanges with Hauser; his address was gacvq@ … , a mordant wisecrack (rendered phonetically it is j’ai assez vécu, or “I’ve lived long enough”). The pair would dip in their exchanges into a curiosity shop of subjects, from popular tropes of cinema to Hauser’s dislike of Apple computers to badger calls, which he once mistook for a woman being attacked in the woods near where he lived in England. Hauser spoke Francique, a dialect of northeastern France. He liked to rock too: He’d played guitar in Les Tigres, a 1960s rock group, and shared a fascination of Phil Spector with Richard Branson, for whom he’d done recording work on his houseboat in London.

Despite this worldliness, Hauser “was not the kind of person who’d talk loudly while gesticulating, or boastful. I always appreciated his immense learning,” Mickey says. One soft spot for him was animals: In an email, he recounted to Mickey how he had stepped in at Avon to stop cosmetics testing on rabbits across the whole company. He suggested they pay nuns (who, after all, could choose to take part) to do it instead; having never worn makeup, their skin was not desensitized to its chemical components. “It’s without doubt the only thing I’m really proud of in my life,” he wrote. This sensitive intellectual forager and friend of animals is disturbingly out of sync with the picture painted by Becker, though of course people can have contradictory facets.

No one in Bourges seems to hold the golden owl’s elusiveness against Hauser. (For his part, he said in an interview filmed for the 10th anniversary that holding the record for the world’s longest-running hunt was an accolade he never wanted. ) Many chouetteurs observe that he simply set the difficulty level too high in his first hunt. He agreed, saying he would have done the puzzles differently “in the sense of going easier on the red herrings—I overdid it a bit.”

Several A2CO veterans admit that they no longer believe they can solve all the puzzles; having grown old together seeking the beast, they are just here for the camaraderie. The owl, a symbol of wisdom, has so far outwitted the chouetteurs and in some cases separated them from their wits completely. Many people tell me they can only search in bursts and have to take breaks—in case they get too obsessive. Hauser at one point in the 1990s started receiving letters from a man who was convinced the prize was booby-trapped, and the author was meaning to kill him.

A certain tolerance for confusion is a requirement in the treasure-hunting game. In the shadow of Bourges Cathedral, a UNESCO-protected hulk of High Gothic architecture, Xipehus, a squat veteran treasure seeker with a side-parted lick of white hair and wine-stained lips, has a last-gasp hunch for the mini hunt organized by A2CO as the day’s entertainment. He reckons he saw a fountain a few streets away with features that might correspond to the “four heroes” cited in one of the decrypted final puzzles. So he, alongside a younger hunter who goes by the moniker N4907, and I charge off down Bourges’s warren of half-timbered houses in pursuit. Halfway there, we pass a man on a bachelor party weekend dressed as a giant bottle. “We’ve seen three golden owls,” he jokes; he’s obviously spoken to other chouetteurs. “We said ‘Twit-twoo’ to them.”

When we reach the drinking fountain, there is no sign or token or anything else. Either someone beat us to it, or it is just a piece of humdrum daily life, not part of a treasure hunt. Xipehus is sweating and rattled looking. A black cat darts by—“It’s the guardian of the treasure,” N4907 says, by way of a consolatory joke. Maybe the bottle guy knew more than he was letting on. In front of the cathedral portico on our way back, Méteor—an elite chouetteur who has won multiple hunts—is clutching the puzzles for today’s hunt, looking harassed. A glider draws a mute line in the sky over the cathedral; is it some kind of sign?

Our brief rush of hope is a window into how these hunts suddenly transfigure reality, turning the most ordinary of places into a hermeneutic playground. Before escape rooms and augmented reality, they were the original immersive fictions, skillfully entwining their participants in their intellectual tendrils. Masquerade kicked off the craze of the “armchair” treasure hunt—for leisure purposes, with specially crafted treasures, as opposed to the genuine kind with pirates and the like. But that hunt came to an ignominious close in 1982 when someone located the cache using insider information. (Creator Kit Williams himself was not involved.) In the United States, Byron Preiss’s The Secret, launched in 1982, remains technically the longest running example in the world; only three of its 12 treasure boxes have been found. (On the Trail of the Golden Owl is the longest-running completely unsolved hunt.) The Forrest Fenn hunt, launched in 2010, became another infamous quest, resulting in the deaths of five people searching in various locations in the Rocky Mountains. It was solved a decade later by medical student Jack Stuef—though, out of respect for what he deemed to be Fenn’s wishes, he has refused to divulge the spot where he found the treasure.

On the Trail of the Golden Owl was the first French example of the genre, but it coincided with a grander expansion in interactive and role-playing fictions. Not only was video gaming beginning to leave its bedroom-programming origins behind and expand into more ambitious forms, but TV gameshows in which players solved puzzles and undertook physical challenges became numerous, such as France’s Fort Boyard and the U.K.’s The Crystal Maze, both devised by Frenchman Jacques Antoine.

As this field has grown in the years since, armchair treasure hunting has become the quaint, squint-eyed uncle of geocaching, Punchdrunk-style interactive theater, escape rooms, Pokémon GO, and others. But it maintains a certain analogue-era rigor. It’s no accident the hunts so often have historical narratives and thrive in heritage locations like Bourges: They’re modern pastiches of medieval quests, whose encounters and challenges are symbolic, and where the true treasure is metaphysical and moral illumination. They might ostensibly be in it for the companionship and the picnics, but what really lies behind the glint in many a chouetteur’s eye? The secret promise of divining history’s hidden order, maybe; or if they haven’t read too much Da Vinci Code, a more private consolation: that behind the arbitrary flotsam of reality lies a set, rational and comprehendible scheme. Maybe that’s the reassurance sought by the depressive personality types many players say feature heavily among their ranks.

That makes it all the more important who creates the scheme, of course. The need for a benevolent and reliable narrator explains the intense partisanship regarding the Golden Owl’s two creators: Who is most worthy of the players’ trust? Many players think the conflict has led the hunt down the wrong path. A2CO secretary Danielle Levasseur is the oldest chouetteur, as she was given the book in 1993 by her neighbor Becker, a day before its official publication—her husband was the postman the artist drove around in his Rolls. Becker was “very excited” by the hunt back then, long before it turned confrontational with Hauser. “The game became too personalized—it’s not healthy. It would have been better if the creators had remained unknown. Then they would have been an abstraction, and the attention would have stayed on the game,” Levasseur says.

Becker seems the obvious choice to ensure the game’s continuity and integrity. He has denounced Hauser’s penchant for red herrings and says the puzzles are coherent and solvable. He claims that, unlike his predecessor’s Madits, he is consistent in his “Midits” (Michel m’a dit—“Michel told me”) on the Discord channel. But he still cannot unite the community into getting behind him as a reliable authority for the hunt. Significant questions remain: about the legal basis for his current ownership of the game and about the provenance of the solutions. But he refuses to comment further on specifics.

Then there is the question of his intentions moving forward. He is launching another hunt, The Treasure of the Entente Cordiale, with two treasure-chest keys, hidden in England and France, respectively. But does he really want to bring his most famous creation, as he publicly claims, to a prompt close? A2CO president Garp is doubtful: “I would say he’s got an interest in prolonging the game because he’s selling books, he’s trying to gather the chouetteurs around him. So, if he stops, he’s going to disappoint everyone.”

In between the Rochefort and Bourges conventions, I receive an email: “By now, you’ll understand that the game is entering its final stages. So I’m proposing to you that you play the role of investigative journalist like the one in Three Days of the Condor.” It is from Yvon Crolet, a notorious former chouetteur who is currently suing not only Becker but also A2CO and Hauser’s family. He alleges, and has for months been publishing on his blogs, that On the Trail of the Golden Owl was a deliberate fraud from the outset. Becker, of course, completely rejects this. Most of the community regards Crolet as a zealot, if not an outright crank. We arrange to meet in mid-May in a hotel next to the grand staircase of the Marseille train station, where he promises to share crucial information. Is he reliable? Can he solve the mystery of the rusted bird? Should I disguise myself on a park bench behind a copy of the International Herald Tribune? I am, I can see, getting sucked irretrievably into my own hunt.

A fortnight later, we are sitting opposite each other in a window booth in Marseille, sipping pints of lager. Crolet is a retired 79-year-old engineer with cropped white hair and wire-frame glasses, tidily dressed in a gray blazer and a checked blue shirt. His mouth is grave, but the tip of his nose is pinched impertinently upward. His son, François—at 50, a slighter version of Yvon—is sitting next to him.

It was François who bought Crolet the book for his 50th birthday in 1994. The son cracked the first puzzle, but it was the father who got hooked. Crolet’s decryptions of Hauser’s puzzles led him to the village of Lus-la-Croix Haute in the mountains of the Vercors national park in southeastern France. As part of a now-defunct chouetteur group called the Conspirators of Hernani (a nod to Victor Hugo’s swashbuckling bandit), he bored into the slopes there on several successive trips in the early 2010s—but found nothing.

“It’s terrible, terrible, the state we were in,” Crolet says.

“Total depression,” follows up François, who put a sign in the countryside around Lus that read “Triste Mont” (Sad Hill, the name of the cemetery where the treasure is buried in The Good, The Bad and the Ugly).

Convinced his reading of the puzzles was precise to the meter, Crolet could come to only one conclusion for the fact that he had dug up nothing: Nothing had originally been buried. Or if it had, the bronze replica had been moved later to prolong the hunt. In 2017, he launched a civil action against Becker and Hauser’s inheritors, trying to force them to reveal the solutions of the game. It is still being considered by a court in Avignon, with the possibility of a criminal trial to follow, Crolet tells me, if the hearings establish some form of wrongdoing. It’s not about the owl, he says, but defending the intellectual integrity of the game—so it doesn’t finish like Masquerade. Given his certainty in his own solution, it follows that he doesn’t buy Becker’s claims of wanting to certify the game after verifying the cache: “Don’t kid yourself. He’s put nothing in order. He wants to get hold of the money Hauser didn’t give him.” But he will say this about the artist: “He could sell stripes to a zebra.”

Becker replies in kind about Crolet, whom he calls a “fouille-merde” (shit-digger). He believes the bitterness caused by Crolet’s failed searches has warped his judgment—“and now he can’t admit that he did all that for nothing. I don’t understand how someone so intelligent, unless they’ve gone off the rails, can maintain that kind of position and insult people.”

Crolet worked as a court researcher after he retired and has fastidiously combed the Golden Owl dossier. His accusations are based on his view that the 1993 book was in effect a binding contract with the players that Becker—as the only living signatory of the Manya agreement—must honor. Chief among the infractions of this accord alleged by Crolet is the fact that, at some point, the solutions escaped the control of the bailiff assigned to legally guarantee them (Becker says he was unaware of this). Perhaps most significantly for the current pack of chouetteurs invested in the game, Crolet believes the Hauser family’s 2021 sale of the game to Becker to be invalid: He claims that they failed to legally declare these rights as part of their inheritance when the writer died in 2009, so he thinks they weren’t theirs to sell. (The family has never commented on this claim.)

Becker admits that the 1990s contracts and books contained ambiguities, such as to whom the rights to the game reverted in the event of bankruptcy, or the fact that the third edition was the first to stipulate that only a bronze copy had been buried, not the gold original. But he believes, despite these discrepancies, the judges will accept the “spirit” in which they, and the post-2021 iterations, were drawn up: to enable the fair continuation of the game.

Where Crolet is in line with many members of A2CO is that he believes Becker’s attempt to verify the cache in October 2021—when he discovered a rusted metal bird instead of his bronze replica—opened up more questions than it answered. The artist had finally acquired the solutions to the puzzles from Hauser’s family in April of that year. With their longstanding antipathy to the hunt and Crolet also on the legal warpath, they were likely glad to be rid of it. (The family did not respond to requests for an interview.)

The spot marked X was specified on a white 3.5-inch floppy disk in a file called SOLUTION.SAM. But had Becker understood the solutions correctly and dug in the correct place? In his written account, the artist said the file—an old Lotus word-processing format—produced 43 pages of mostly gibberish when opened. But there were legible phrases, which he copied and combined into 10 pages that specified the bird’s location. Assuming he correctly transcribed it, isn’t it possible the encrypted text contained important elements? (Becker refuses to elaborate on this.) Then there was the matter of the rusted bird. Becker currently theorizes that Hauser, in his mid-2000s panic when the gold statuette was seized, swapped out the bronze replica in order to prevent a prospective finder from being able to claim the prize. But if so, why leave a token there to mark his transgression?

And were the solutions even the ones originally deposited with the bailiff in May 1993? After his death in 2009, Hauser’s family found the disk and a red envelope in the vault of Hauser’s own bank, not under independent bailiff control. According to the original bailiff’s deed, there should have been an envelope containing a paper copy of the solutions, as well as the disk. But the red envelope delivered to Becker in 2021 only held a card with a poem congratulating a prospective winner. What had happened to the first envelope? Could the secret have found its way into someone else’s hands? With the disk out of bailiff scrutiny for a number of years, no one could be certain that the solutions on it hadn’t been altered—or that they even corresponded to the ones in the AWOL envelope. Becker, in a 2010 open letter to the chouetteurs, acknowledged this possibility: “I continue to believe that in withdrawing the solutions from the bailiff and entrusting them to third parties, Régis Hauser took the risk of definitively compromising the game.”

Becker insists he has done his utmost to rectify these ambiguities—including replacing the rusted bird with a bronze replica. But if he has misinterpreted the solutions, or Hauser deliberately misled everyone, it is possible two bronze replicas are buried out there now. “In football, when there’s a second ball on the pitch the referee stops the game immediately,” Garp notes. He believes Hauser, for the sake of the game, to have been well capable of obfuscation. “He was very, very cautious. [Fellow treasure hunt author] Phil d’Euck used to say all the time that he would never confide the solutions in their entirety to a bailiff or anyone else.” So it’s possible that the rusted bird Becker found was another Hauser red herring to tease treasure hunters at the wrong spot—and that the real bronze (the first one) is buried somewhere else entirely.

Crolet has some tricky questions for Becker too, asking why it took him six months from decrypting the disk to checking the site. (Becker doesn’t explain the six-month gap, but in the preface of the latest addition of the Golden Owl book, he does detail a series of preparations necessary before he successfully checked the cache site. And of course he has strongly denied tampering with the solutions.) Crolet also points to what appears to be a startling impropriety: In 2006, in a fit of pique during the furor over the statuette seizure, Becker proposed to two seasoned treasure hunters, Argos and Paco, that they team up to search in their preferred Auvergne dig zone. He gave them exclusive access to the instructions Hauser had given him to make the illustrations for the book and ensure that they corresponded with the riddles. Those guidelines didn’t contain the full solutions but might help them bridge the gap. He searched with them again on two separate occasions, in 2018 and 2019. How can he not have realized how damaging this favoritism was for the game’s credibility? (He refused to discuss these searches, but claimed on the Discord channel that he had not unduly influenced the game.)

A brainiac whirlwind of pedantry, Crolet was born to keep legal officials on their toes. His black-and-white outlook and intransigence remind me of Rorschach, the vigilante in the graphic novel Watchmen, willing to sacrifice himself to maintain moral absolutes. His strategy is dangerous. If Crolet loses the trial, Becker has said he will probably bring a defamation suit, because of the slurs and sarcastic broadsides Crolet has let loose on his blog. Crolet is the game’s ultimate player, totally convinced of his reading and just as invested in his narrative of a grand conspiracy as he was in the fiction of the game.

But it’s notable that Crolet reserves all his enmity for Becker, when Hauser appears to have been responsible for the early disarray miring the Golden Owl hunt. “It’s a question of feeling an intellectual proximity, because [Hauser] conceived a great game,” says the chouetteur. “Hats off to him! All the rest, the little schemes he did around that—I would explain by saying he wanted to make easy money. We can forgive him that.”

Despite it all, Crolet retains a bruised faith in the cult of Max Valentin—and in the presiding order of the game. He believes the puzzles to be coherent, and the first bronze owl to be out there somewhere. But for his son François, none of it means anything anymore: “The thing is there is no solution.”

Crolet cocks his head: “That’s where I don’t agree with you.”

In one place everything begins / At one point everything ends. / Going from one to the other, clasped between her hands / Pierrette’s rose, Valentin’s gift / Has sown its petals, like little white pebbles / While hesitating, measured, rhythmic, / To the end of the road her steps had carried her, / As in another world of which she would be the center, / Diligent and zealous, Pierrette came to understand … / By the golden owl, finally, she would be surprised.”

The throng at the AOC gathering in Rochefort is avidly leant in, listening to a recording of Becker—in alternately punctilious and cozy storybook tones—read out this tantalizing, chouetteur-baiting poem, entitled “Pierrette et le Pot-Aux-Roses.” Then they erupt in cheers, as the artist basks in the adulation. Just like one of the clue drops in the Steven Spielberg film Ready Player One, it is intended by Becker to induce the “déclic” (lightbulb) that will permit someone to understand the super-solution and finally unearth the owl. Within seconds, the chouetteur hive mind around me is already in overdrive.

The pot-aux-roses is a reference to a medieval custom in which women hid letters or other love tokens in flowerpots; secrets to be discovered. Pierrette, derived from the French for rock, could be a pointer regarding the sentinels in the puzzle. Or is, as some internet commentators later point out, Pierrette’s rose alluding to the Pierre de Rosette (Rosetta Stone), hinting that a further decipherment was needed? The week after the drop, so many people go and dig holes around Dabo that the village’s mayor issues a complaint to Becker about the damage. The Discord channel is fervid with debate. The artist has everyone on tenterhooks: A few people are close to the shift in thinking required, he confirms, even if they don’t know it.

Dabo is not the only zone of interest. Someone has decided to send Crolet on his own personal treasure hunt. Two days after the Rochefort bash, he receives an anonymous letter containing a photograph of the red envelope bequeathed to Becker from Hauser’s family, confirming for the first time that its wax seals had been broken. Printed beneath the photograph is the message: “The key is hidden in Argentat.” (This is the Dordogne village where the bailiff who certified the golden owl cache site for Becker is based—presumably a nod to the fact that vital information concerning the Golden Owl hunt is kept there).

After Crolet publishes the photograph on his blog, Becker responds on YouTube days later to quash speculation that the envelope contained the solutions, potentially exposed to third parties. At the end of an orotund 46-minute video reeling off a long parable, he discloses footage of the opening of the red envelope and its contents: simply, the message for the winner. Seemingly targeting you-know-who, he takes the opportunity to denounce “the unhealthy covetousness of the jealous, the embittered, and other conspirators.”

Crolet’s mysterious whistleblower felt the chouetteurs were owed more. His next missive contains a sheaf of documents that, if authentic, includes the full unredacted versions of emails and other documents submitted by Becker at the Avignon hearings. On one, an email confirming the Hausers’ first appointment to meet with the artist to discuss rights to the game, is marked: “The key is hidden in Rueil” (a western suburb of Paris). On another document, the interloper appends a set of GPS coordinates.

In early May, days before our Marseille meeting, Crolet follows them to a chunk of national forest on the south edge of Rueil, where he finds a flayed-out tree stump. There is an owl sculpted at the top: “Things were starting to smell good,” he chuckles. In a crack at the base of the stump, he spies a flash of color. Prying the object out, he discovers it is a USB key in the form of Batman’s nemesis, the Joker. When he accesses its contents at home, he finds a cache of documents totaling two gigabytes, including purportedly confidential emails that, originating with Becker’s bailiff, were held in a special secure mailbox for officials of the legal system.

Another encrypted clue soon arrives on a vintage 1930s postcard. When Crolet gets to the house depicted on it, in ruins in more woodland northwest of the capital, he is confronted on the outside wall with a graffitied mural of a vast leering Joker. Nearby, Crolet and other chouetteurs he’s enlisted in the search find a geocache: a roll of paper with a list of meridian and altitude coordinates that appear to correspond to solutions for the first 10 puzzles. At the bottom is the message: “These 10 pages are hidden on the 43 pages hidden on the key hidden in Argentat.”

There the trail stops. There has been no revelation of intentional fraud so far. But more cracks are appearing in the Golden Owl’s carapace. The video of the envelope opening was not dated, and Becker now refuses to confirm when this took place. The Joker’s documents suggest Becker opened it in 2021. But did he? He won’t now say. It seems he only revealed he’d broken the seals when forced to do so by the Joker’s photograph. Why hadn’t he declared that earlier? As late as July 2022, with the introduction to the fifth edition of the Golden Owl book, Becker gives the impression it had remained intact: “Vexed, I had to resist my desire to unseal the envelope.”

But were they still intact then? Becker will not clarify this, nor any other details about his verification of the cache, the solutions, documents that substantiate his account of the game’s history, or the recent leaks. After initially cooperating with me for this article, Becker abruptly withdrew in early May; later, when I sent him a list of questions regarding these things, he said he did not wish to stoke “controversy.” In an email to Narratively, Becker called my questions “a mass of rumors and gossip,” which he is refusing to answer “because they relate to information collected from people who have no proof of what they are saying and refers to documents which were provided to him by someone who has them illegally and whom my lawyers are going to take to court.” When asked again to comment in more detail to each of Crolet’s allegations prior to publication, Becker replied that “most of Mr. Crolet’s assertions are false.” Becker has tried hard to establish the narrative of his stable custodianship of the game. He quickly shuts down people who probe into the gray areas, saying he alone is in possession of the facts. But as the envelope episode shows, there are questions over whether he has always been fully transparent. It is natural to begin to wonder about other semi-knowns: Becker’s account of his partner’s alleged untrustworthiness and the precautions taken over the solutions down the years. How reliable a narrator is he? One striking thing is how much his characterization of Hauser’s past has served to bolster himself. In one Discord, he condescends toward Hauser as “no scholar” but rather as someone who “manipulated language well” to “draw on popular culture.” Which is not entirely fair: Hauser was Jesuit-schooled in the classics and, according to his friends, was an uncommon storehouse of cultural knowledge.

Possibly Becker didn’t know him well enough, but he permits himself to speak for him all the same: Hauser was the lowly panhandling salesman, desperate for money, in contrast to him, the roving aesthete. But he is currently monetizing the Golden Owl hunt (with some justification, if what he says about Hauser hoarding the profits is true). The Chouette d’Or museum and Lingot d’Art bar in the former Rochefort water tower are tied up with Becker’s myriad real estate ventures. Down in the crypt, it’s notable how the 30th anniversary chouetteurs are forbidden from photographing the golden owl (which he has registered as a trademark), presumably for commercial reasons.

The bronze owl remains underground after more than 11,000 days. Becker’s AOC clique remain valiantly on its trail, with many people feverishly speculating it will be found anytime now; the A2CO internet forum, like a school of medieval monks, beavers away as diligently as ever on the minutiae of the solutions. Rare are the players who will give the apostate Crolet any credence, but even they are too caught up in the game to really examine the substance of what he says. The game is still running, and that’s what counts.

Perhaps Becker’s true faux pas in the eyes of the older chouetteurs is having failed to live up to the mythical master of ceremonies that was Max Valentin, by being too expedient with the game. Trying to take the game in hand, he turned on his late collaborator, attempted to sell the owl and was perhaps prepared to go further by privileging certain players.

The more Becker plays the unflappable gamemaster, the more Max Valentin looms behind him. The perfect fictional construct must disguise its inner workings. But, even more persistently since Hauser’s death, the Golden Owl’s own constructs have popped out as painfully as hernias: the attempted auctioning, the bitter partisanship, the endless speculation over the cache and the solutions. Becker might have found his rhythm now, intent on leading the chouetteurs forward. But always insistently, drawing attention to himself. Not like Valentin, directing from the shadows, getting everyone a little lost, all the better to find themselves. With so many stumbles en route on his watch, that all-important illusion is gone: that the chouetteurs are uncovering the story themselves. Becker may say they are writing the hunt now—but he certainly likes reminding them that they’ve borrowed his pen.

Régis Hauser could still give him lessons in the art of the tease. On his blog, Hauser’s former neighbor Monglane remembers one of many evening tête-à-têtes with his friend. Perhaps they were on chaise longues in his garden on one of those endless summer nights, or cradling whiskeys by the fireplace in winter—he no longer recalls. But he does remember Hauser dropping a bombshell: that, given how he felt a moral duty to answer every Minitel inquiry he received, he had devised a set of questions that, if posed in correct order, would force him to reveal the owl’s location. Seven of them, to be exact. On the spot, Monglane couldn’t come up with a single one. “I was too stunned for my brain to produce anything useful that evening … especially opposite that little smile of Max’s, who knew perfectly well what was going on inside my head.” All you ever had to do to find the golden owl, it turns out, was ask.

This story was originally published on Narratively, an award-winning storytelling platform that celebrates humanity through the most authentic, unexpected, and extraordinary true narratives. To read more from Narratively and to support their independent journalism, subscribe to their newsletter.

This story originally ran in 2023; it has been updated for 2024.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook