The Radical Reference Librarians Who Use Info to Challenge Authority

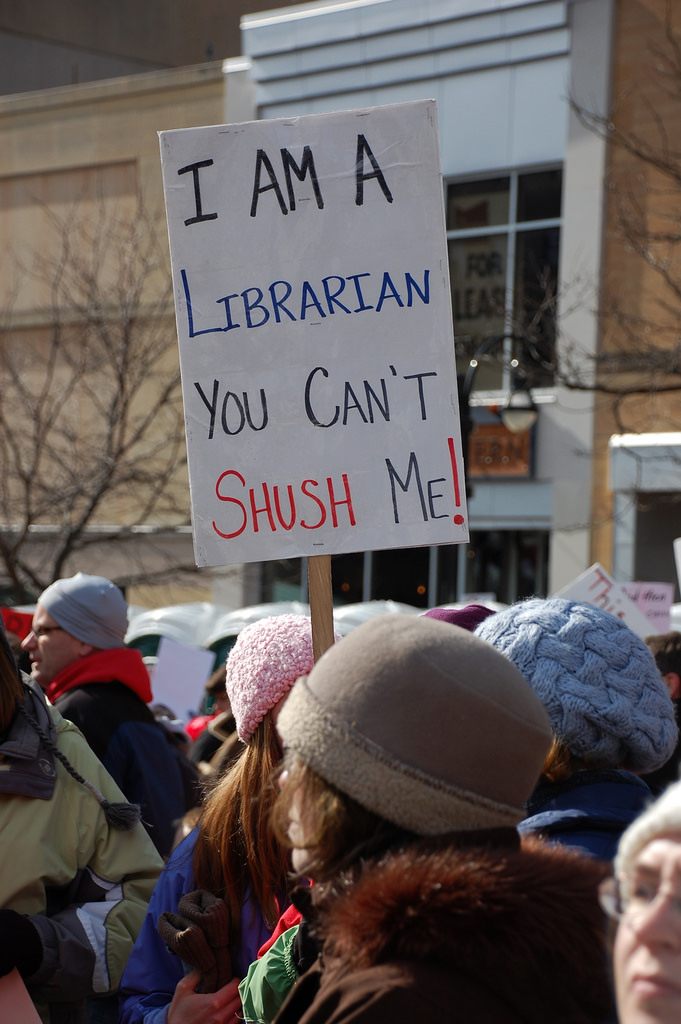

An unshushable social movement is afoot.

From August 29 through September 2, 2004, a series of protests erupted in New York in response to the 2004 Republican National Convention and the nomination of George W. Bush for the impending election. Nearly 1,800 protesters were arrested during the convention, and later filed a civil rights suit, citing violation of their constitutional rights.

During the protests, a steady team provided support to anyone who needed information amid the confusion: a modest group of socially conscious librarians from around the United States, armed with folders of facts ranging from legal rights in dealing with police to the locations of open bathrooms.

“We wanted to operate as if we were bringing a reference desk to the streets,” explains Lia Friedman, Director of Learning Services at University of California San Diego, who was at one of the protest marches in 2004. At the time, fewer people had smartphones, making this service both new and important. When someone asked a question that wasn’t included in their traveling reference desk folders, other librarians waiting at their home computers were poised to research and deliver information by phone.

The group of librarians soon formed into the first-ever chapter of the Radical Reference Collective, a non-hierarchal volunteer collective who believe in supporting social justice, independent journalists, and activist causes. Since the group’s first action at the Republican National Convention of 2004, the group, originally based in New York, has spread across the United States as a collection of individual local chapters. New collectives formed via library listservs, the Rad Ref’s website, and word of mouth.

Because the organization is non-hierarchical, there is no consensus on exactly what the “radical” in Radical Reference really means, nor what kind of work it might imply. Members come from different backgrounds; one New York City Rad Ref member is personally involved with a group that provides street medics training to help people medically during protests; other members are from academia or are involved in work with prisoners or science archives. The website for Rad Ref points out that in no way does the word “radical” specifically denote a political affiliation of any kind; the word “radical” is used to challenge “mainstream meaning which largely marginalizes the term and along with it certain groups.” But, members do form their own opinions on the matter.

“In my opinion, using the word ‘radical’ means advocating for change, whether that is political, societal,” says Friedman. Audrey Lorberfeld, Digital Technical Specialist at The New York Academy of Medicine and longtime member of the New York Rad Ref group, says that this inherent politicization of information is apparent to librarians regardless of their specialty: in the introductory information sciences courses for those pursuing a Masters of Library Sciences in the U.S., librarians-to-be become well-versed in the American Librarians Association code of ethics, which includes intellectual and informational freedom. According to both Lorberfeld and Friedman, who were interviewed separately for this article, to many librarians, the idea that information is neutral is a myth.

Now, amid a divisive political climate in the U.S., the original New York group is continuing to provide open-access information for all, be it about a specific historical fact, civil rights infringement statistic, or the complex laws regarding immigration. Often this support is lended to social justice organizations, independent journalists, and, as their website states, “anyone who questions authority.”

Some of the Rad Ref groups use social media to communicate and promote events, talks, and workshops with the public and activist organizations, while others meet face-to-face. The topics vary wildly; some events may concern more local issues, like planning support for a library worker strike, while others could involve “creating or using a resource guide on a relevant issue, i.e. Black Lives Matter, Critical Librarianship, Fact Checking basics” says Friedman.

Rad Ref has sizzled in the background of protests, local workshops and activist groups across the U.S. since its inception, although participation varies, and each local group is unique. Friedman spent years providing information through the Rad Ref website, which formerly acted as a virtual reference question desk. More recently she has participated on a smaller scale within the San Diego group, which sometimes has only a few members; both Friedman and Lorberfeld noted that since librarians tend to be involved in multiple projects and membership is voluntary, the numbers of a group can fluctuate. Occasionally, the groups have gone on hiatus, as the New York group’s online reference presence did in 2013, when its members didn’t have time to devote to the struggles of running a volunteer-based organization.

That hiatus hasn’t lasted, though: New York City’s Rad Ref was reinvigorated after President Donald Trump took his oath of office in early 2017. And these librarians are ready to radicalize their role as information champions. During their first meeting post-hiatus, the room was overflowing with activists and librarians who deeply cared about organizing to preserve information. “It was an amazing feeling,” says Lorberfeld.

Right now, the New York group’s goal is to build a community of knowledgeable experts on the art of finding and delivering information, which can become a resource for librarians and activist organizations alike. “We’re trying to look inward and educate ourselves, from anything from immigration rights to grassroots organizing best practices,” says Lorberfeld. “One member is making a guide about Unions in New York City; what they are, how to join them,” and another is creating a map of available free meeting places for organizations throughout the city.

Friedman and other Rad Ref volunteers once helped a writer who was working on research for a nonfiction book on resistance and struggle within women’s prisons, for example, and needed access to statistics and facts that were not easy to find, such as the amount of prisoners in a specific county in a specific year. Through the website, Rad Ref librarians were able to provide specific numbers she used throughout her book by pooling their skills in data research and law. While the reference service aspect of the website has been inactive since the hiatus, the website is still available as an archive, and librarians will still answer the occasional question in the Rad Ref inbox.

It might seem like information is open to everyone today: the internet is common and most people know how to type a sentence into Google. But as Friedman and Lorberfeld explain, there’s often more to it than that when trying to find specific and often very meaningful details and information. Sometimes, the only thing keeping data from, say, a government website like that of the Environmental Protection Agency from being removed or tampered with by politicians may be the librarians, working behind the scenes to preserve that information—something that actually happened earlier this year.

“We used to teach that a .gov site was trusted. And that’s a little bit more challenging to do now,” Friedman says. A Google search often isn’t curated or necessarily fact-checked, and doesn’t always provide multiple and balanced sources. Sometimes key information is behind an academic journal’s steep paywall, or buried in government documents under specialized lingo. “We really wanted to support independent journalists and activists, and really wanted to give people access to information, which is a pretty librarian thing to do,” says Friedman.

It really is a pretty librarian thing to do. Despite librarians’ public image of glasses-clad women hushing pesky kids, library workers around the world, from South Africa to Sweden, have formed similar organizations to Rad Ref, according to Alfred Kagan in his book Progressive Library Organizations: A Worldwide History. Since the 1960s in the United States, many library workers have committed to “social responsibility,” the democratic giving of information to the public and to free speech. Kagan writes that progressive groups have used their independence from the American Librarians Association (ALA), the major national librarian group in the U.S., “to take radical stances.”

A subunit of the ALA includes the Social Responsibilities Round Table, which has, according to its website, worked to democratize the ALA with human and economic rights in mind since 1969. Similar groups exist around the United States, such as the Progressive Librarians Guild, which aims toward an international agenda. Rad Ref participates in this tradition, though it differs in that it’s comprised of local librarian groups who work within their individual volunteer base’s skills and goals, without a central governance.

“We all sort of have a really core sentimental belief of information access as a human right, and I feel like that really governs what we do within the group,” Lorberfeld says. By using their diverse backgrounds and talents, Rad Ref is now readying itself to help activist groups by promoting information that aids in furthering social equality.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook