You Can Still Die From World War I Dangers in France’s Red Zones

The Great War never ended in some old battlegrounds.

In some parts of France, World War I has never ended. These are the Zones rouges—an archipelago of former battlegrounds so pockmarked and polluted by war that, more than a century after the end of hostilities, they remain unfit to live or even farm on.

WWI was the first industrial war and a laboratory for all kinds of military innovations, including the first use of tanks and poison gas. Both the German and the Allied war machines belched out deadly explosives and lethal chemicals on a massive scale. It is estimated that around 60 million shells rained down near Verdun during the fierce battles over that city in 1916—of which 15 million didn’t explode upon impact.

Four years of war stripped a zone on either side of the largely immobile frontline of any sign of life. Roads and bridges, canals and railways were destroyed. Cities were pummeled into dust. Entire villages “died for France” and were wiped off the map for good.

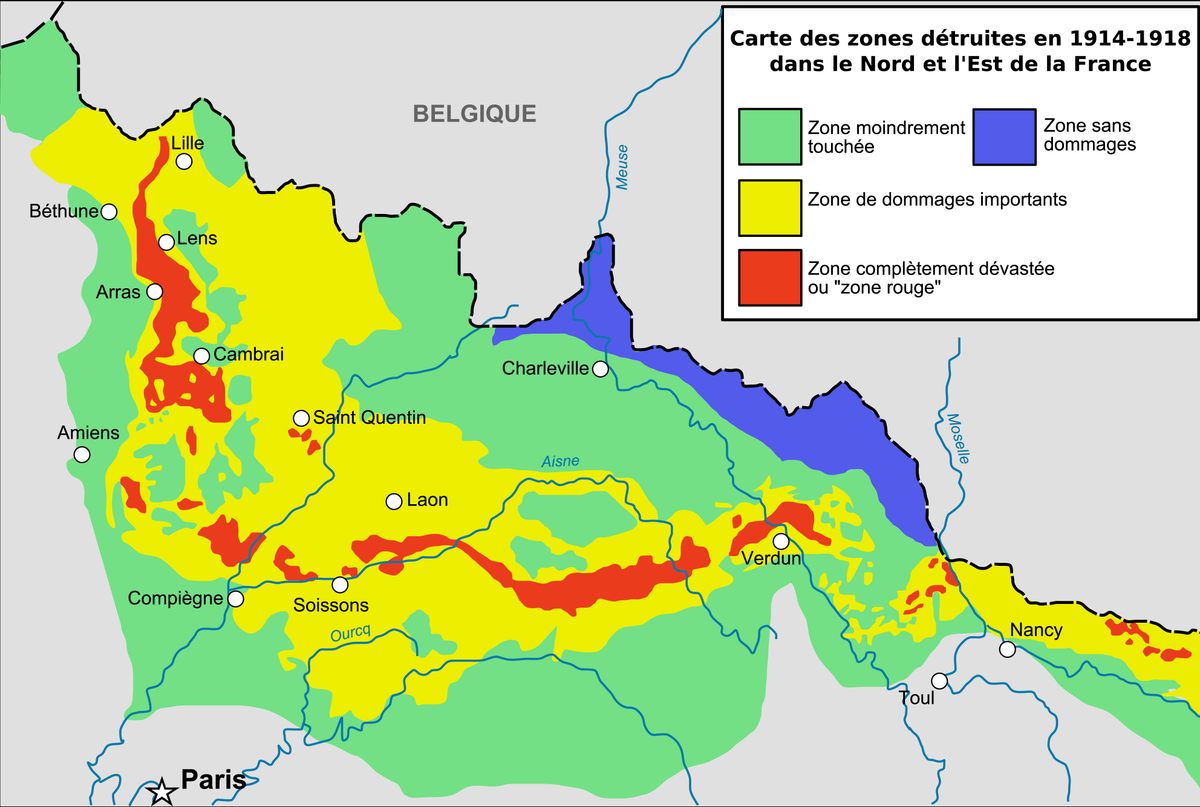

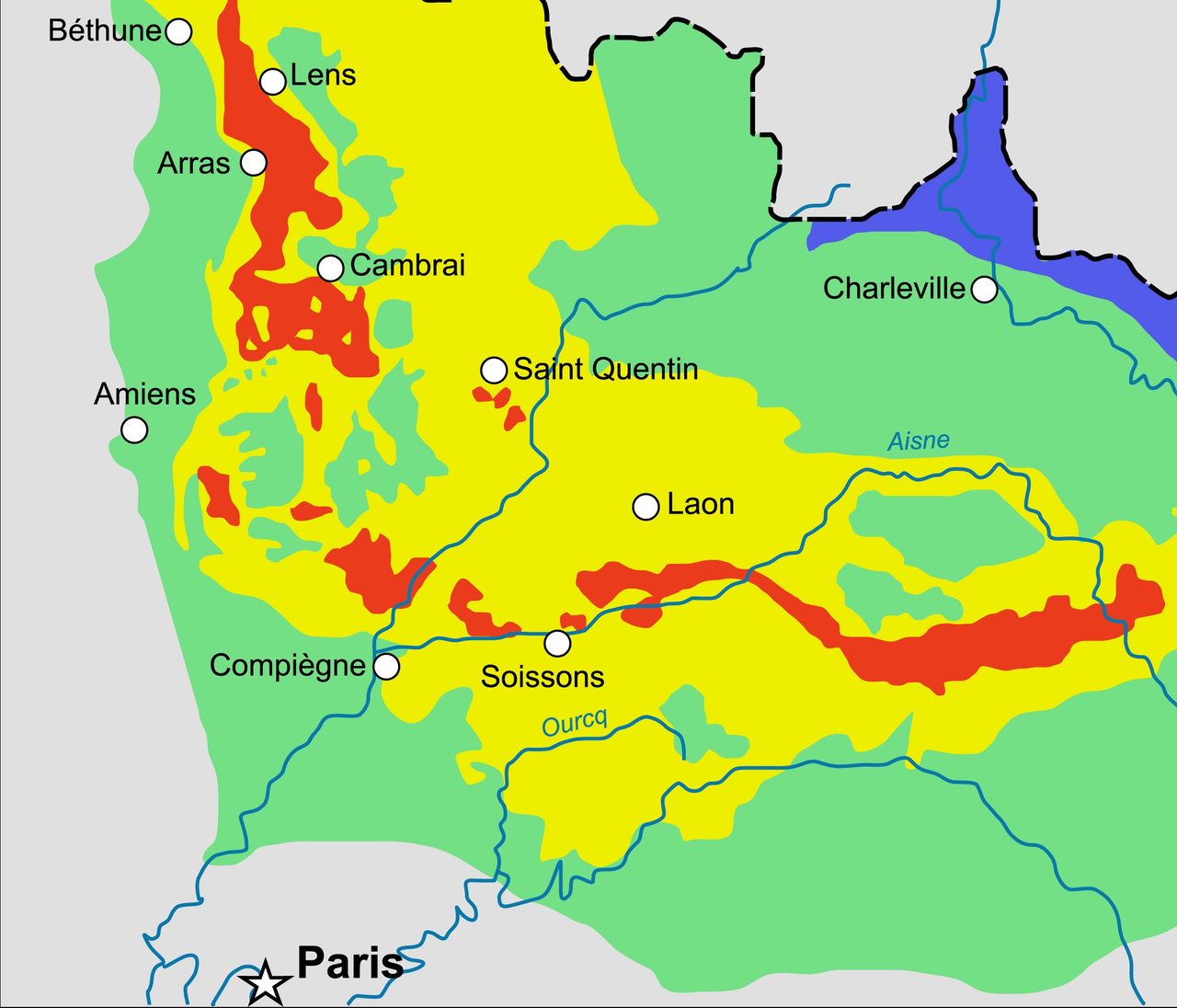

Bombardments were so thorough that even grass and trees disappeared. When the war ended in November 1918, a large swathe of northern to eastern France was so cratered up and chewed out that it looked like a moonscape. In all, about 7 percent of French territory was destroyed during the war, in a zone stretching over 4,000 municipalities across 13 departments, from the Nord at the coast to the Bas-Rhin on the Swiss border.

By 1919, the French Ministry for the Liberated Territories had divided the afflicted areas into three zones, depending on the degree of destruction:

- Zones vertes (“Green Zones”), with minimal damage;

- Zones jaunes (“Yellow Zones”), with heavy but limited damage; and

- Zones rouges (“Red Zones”), usually closest to the former front lines, which were completely destroyed.

The primary task was to clear the affected areas of ammunition and corpses. This involved the efforts of German PoWs, foreign workers from as far afield as China, and Quaker volunteers, among others.

Massive amounts of unidentified human remains were gathered in places like the Douaumont Ossuary, the last resting place of 130,000 German and French soldiers who fell at Verdun. Soldier bones continue to turn up. As recently as April 2012, authorities were able to identify the remains of a French soldier named Albert Dadure.

The green and yellow zones were returned to civilian use relatively early. The red zones were different. They were, in the words of one official post-war report, “completely devastated. Damage to properties: 100%. Damage to agriculture: 100%. Impossible to clean. Human life impossible.” Red zones were cleared only superficially, and mostly just closed off.

In 1919, these red zones covered around 690 square miles (1,800 kilometers squared). Here, the ground remained saturated with unexploded ordnance. High concentrations of heavy metals and chemicals in the soil further increased the risk to life and limb. For reasons of safety and sanitation, these areas were strictly off-limits for housing, farming, and even forestry.

By 1927, the red zones had been reduced by 70 percent to around 190 square miles (490 kilometers squared), in part due to pressure from local farmers, who wanted to return their fields and pastures to productivity and profit.

Today, the red zone archipelago has shrunk to about 40 square miles (100 kilometers squared), about the size of Paris. Yet it’s unlikely that these islands will disappear soon. They are the most tenacious residue of a long-lasting environmental problem.

Each year, farmers in former red zones plough up an “iron harvest” of close to 900 tons of unexploded ordnance. Near Verdun, road signs point to dumping grounds where they can leave these shells for the authorities to collect.

France’s Sécurité Civile, which is charged with removing them, estimates that at current rates, it could take up to 700 years to completely clear all remaining WWI shells and grenades from France’s soil.

And then there are the gases, acids, and other chemicals polluting the soil—in some parts, the ground still contains so much arsenic that nothing will grow. In less affected areas, biologists still note the lack of floral and faunal diversity related to the pollution, which some estimate may take about 10,000 years to clear.

WWI was supposed to be the “War to End All War.” That went… less well than could have been hoped for. One of the lessons not learned from that conflict is that modern wars have long-lasting impacts on health and the environment. The issue has remained largely dormant, resurfacing only in the 1990s, when more than one in three U.S. veterans of the First Gulf War reported a range of symptoms ascribed to exposure to toxic substances.

Even in France itself, not much thought is given to the lingering effects of WWI, or to the remaining Zones rouges—perhaps because so much of the affected areas were left to the trees, becoming so-called forêts de guerre (war forests), notably in the Champagne region. Yet the invisible environmental legacy of the Great War has very real consequences.

- In 2012, the consumption of locally sourced drinking water was prohibited in 544 municipalities, due to high levels of perchlorate, which was used to make WWI ammo. All of those municipalities are located close to former battlefield zones.

- Experts warn that mushrooms, game meat, and even food cooked over wood collected in red zones or former red zones might be a source of toxins.

- It has been established that the livers of wild boars roaming the forests around Verdun contain abnormally high levels of lead.

- And the relatively elevated levels of lead in certain French wines may result from the wood of the barrels in which they matured, from oak harvested in former red zones.

This article originally appeared on Big Think, home of the brightest minds and biggest ideas of all time. Sign up for Big Think’s newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook