The Vintage Japanese Copy Machine Enjoying an Artistic Renaissance

Launched in the 1950s, the Risograph has been repurposed.

At a New York storage space some time in 2010, printmaker Pan Terzis was left alone with a friend’s Risograph machine. The friend “told me he got this machine that was like a screen printing machine, but automated,” Terzis says. “I see this weird old copy machine and was like: ‘Where’s the Riso?’ And he said, ‘This is the Riso!’”

Within 24 hours, Terzis had used the machine to print a 50-page book, joining the ranks of 21st-century artists and publishers who are using old technology to make new creations.

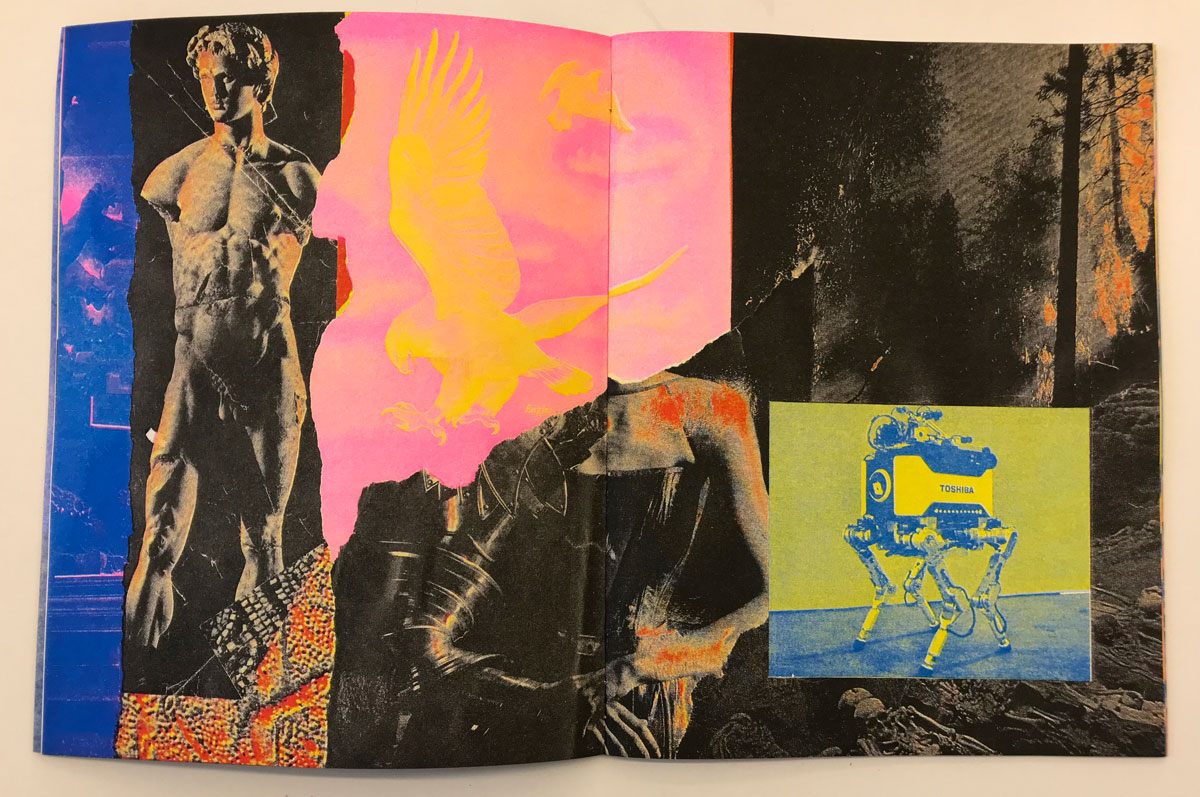

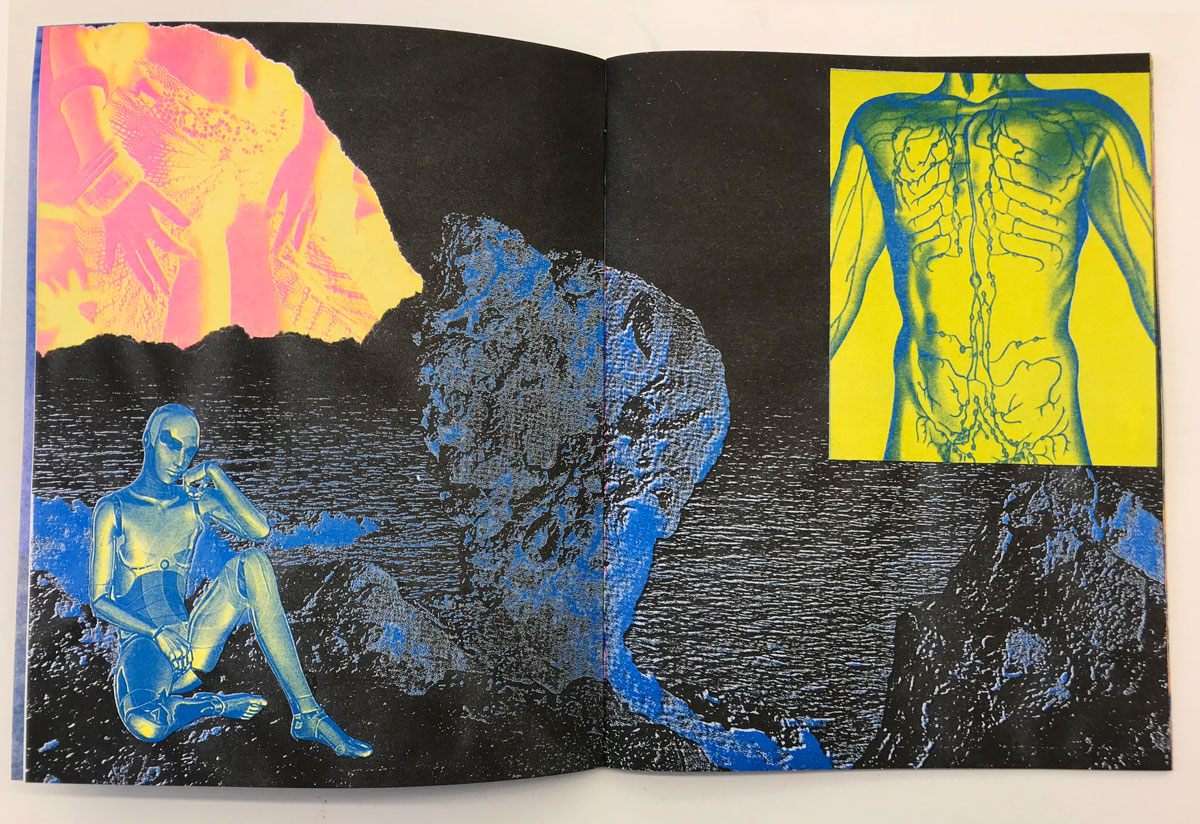

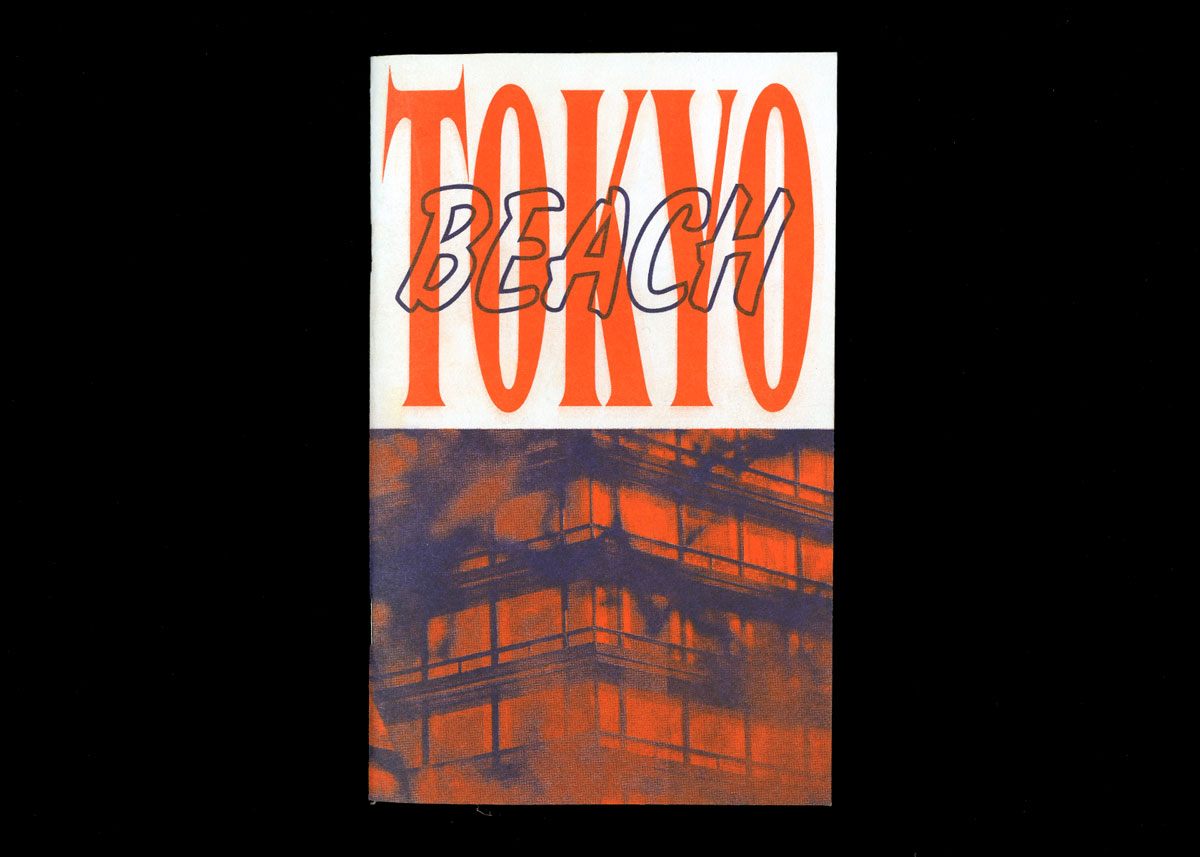

The Risograph, a machine that duplicates like a mimeograph but dispels ink like a screen printer, has come a long way from its humble 1958 beginnings in a small home in Tokyo. Originally intended as more of a courtesy to Japanese businesses than a printmaking phenomenon, this ordinary, grey machine’s bulky exterior belies the innovation within. Around the world, the Risograph is now used by independent artists and publishers to create unique, high-quality zines and art prints. Aside from the vibrant ink it uses and the relatively low overhead costs it demands, it insists on the use of both digital and analog printing methods (it prints computer-generated designs but the ink drums must be handled manually), which makes for an equally modern and nostalgic experience.

The Risograph’s automated efficiency is what made it a hit amongst Japanese offices initially, to be sure. But the speed with which it can spit out prints is only a small part of why the machine is having its renaissance.

On the School of Visual Art’s campus in New York City, there’s a printing lab dedicated exclusively to the Risograph; an interdisciplinary space for printing, publishing and the production of Risograph-based printed works. The walls are lined with posters, whose faded ink could be mischaracterized as “vintage” if not for the mechanical murmur of the two machines shooting them out in real time. Some of the students are designing their prints on surprisingly smudge-free computer screens, while their counterparts wield industrial-size staplers around the room, waiting for their zines to dry before binding. In a smaller room that sits just off the larger one, the oldest (yet fully functional) Risograph is occupied by a student soaking up her last minutes of scheduled time with it, watching patiently as the “warm red” ink drum presses her design into life.

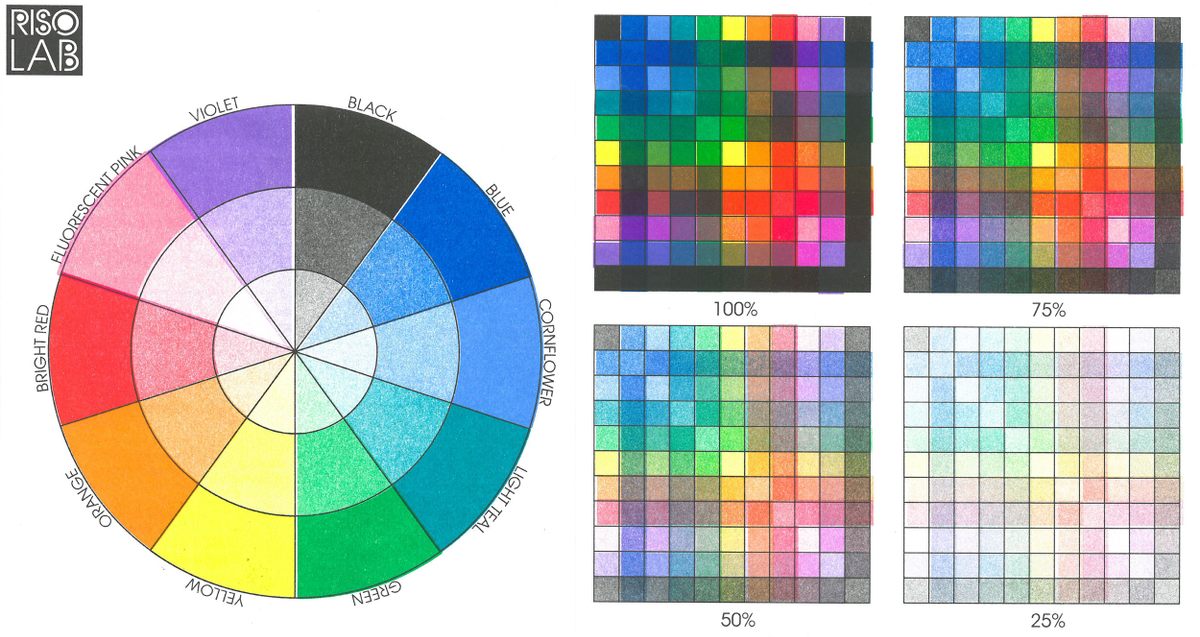

The Risograph machine operates by burning a stencil of an image into a fiber-based master, which is then wrapped around a color drum that pushes the ink onto the paper, thus creating a print. Similar to silk-screening, the stencil duplicator only prints one color at a time; to create a duotone image, the paper is run through the machine again, this time against a different color drum. The RisoLab recently got its third, and most modern, Risograph which allows for two color drums to run at the same time. Terzis says the most common color combination is pink and blue. The ink brings vivid saturation to the page, and is just unwieldy enough to give indie publications an imperfect, handmade feel.

Before the Risograph was an artist’s printmaking tool, it was a machine born out of necessity. Following the end of World War II, emulsion ink was only available in Japan through an expensive importing process that relied on unreliable trading channels. This was a direct result of Japan’s strategy to use high tariffs on American and European industrial products, thus limiting money spent on outside materials as a way to recover from their period of economic depression. On a quest to bring a cheaper alternative to the market, Noboru Hayama devised “Riso,” a soy-based ink ideal for high-quality color printing at an affordable price.

The Risograph machine Hayama developed in tandem with his new ink promised to be a more efficient and environmentally friendly duplicator than its competitor, the photocopier. When this offset-laser-screen-printer hybrid finally entered the American marketplace as the company’s first overseas sales subsidiary in 1986, it revolutionized short-run prints for places like schools, churches, and businesses; for anyone looking to print duplicates between 50 to 10,000 copies, the Risograph was their answer.

Matt Davis, the owner and operator of Chicago’s Perfectly Acceptable publishing house, thinks the relatively short lifespan of Risographs is what allowed them to move from utilitarian quasi-photocopier to a tool for artists. “As far as photocopying technology, [Risographs] don’t age very well,” he says. “So they ended up on the aftermarket for very cheap, which was great for artists who snapped them all up.”

Davis, who got his first Riso for free from a post office in Ohio, says the underground Riso world felt like “the Wild West” when he started his print studio in 2013. As Nichole Shinn, one-fourth of Brooklyn-based publishing collective TXTbooks, notes, the Risograph “was never intended to function as an artistic exploration, but that’s what makes it so interesting to a lot of people … trying to navigate different ways the printer can be used creatively.”

Independent publishing houses like Perfectly Acceptable and TXTbooks are helping turn the grainy likability of Risograph printing into a global aesthetic. The myriad color combinations that are possible (Davis’ favorite being “mint and sunflower, 100 percent,” and Terzis celebrating the mix of “any of the complementary colors, because when you put them together they really vibrate”) makes it seem like the Risograph was destined for artistic flourish all along. But Issue Press founder George Wietor challenges the idea of the Riso’s “look” overshadowing its intended purpose: “The simplicity of the Riso brings a specific kind of arts publishing within reach and allows me to work with ink and paper in a way that I would otherwise have difficulty achieving,” he says, “but I am (only very mildly) concerned about elevating the Riso to something more than it is or, I believe, should be—which is a means of production rather than a specific style.”

Today, you can buy a Riso on eBay for just under $1,500. But the much-beloved machine is not without its limitations. Uncoated paper absorbs the nontoxic inks best, so printing on luxe, glossy paper is generally discouraged. And ink color choice is limited, though several, Venn diagram-style overlapping print runs can create colors (albeit occasionally muddy) outside of the traditional CMYK color spectrum we’re used to.

“My fear has been that artists using Riso in this way is an unsustainable fad,” says Terzis, “but I think [the Riso] needs to become less precious so that we notice that something is Riso printed, and that’s great, but what did [that person] do with this medium? Because at the end of the day the medium is neutral.”

There’s a whole atlas, organized by country, dedicated to Risograph publishers, print shops, and design studios using the duplicators. Created by Wietor, this directory is just one part of a larger Risography database and illustrates how widespread this printing machine’s impact has become, particularly in the United States, Canada, and Europe. “The Atlas of Modern Risography … actually came out of a kind of loneliness,” says Wietor. “When I first started I only knew of a handful of friendly presses in Europe, so I started the Atlas as a method of learning about other presses with the thought that we couldn’t have a community if we didn’t know that each other existed.”

It’s clear that community is at the center of the RisoLab’s mission.“It’s a beautiful thing, publishing and printing is all about communication and community,” says Terzis. “You can’t just work in isolation, we’re all in a social context. We can’t survive alone, we need other people. I think printmaking reminds you of that, especially Riso printing.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook