The Historic Pub That Holds Its Own Olympics

Rohman’s Inn is the last relic of a buried-and-gone amusement park.

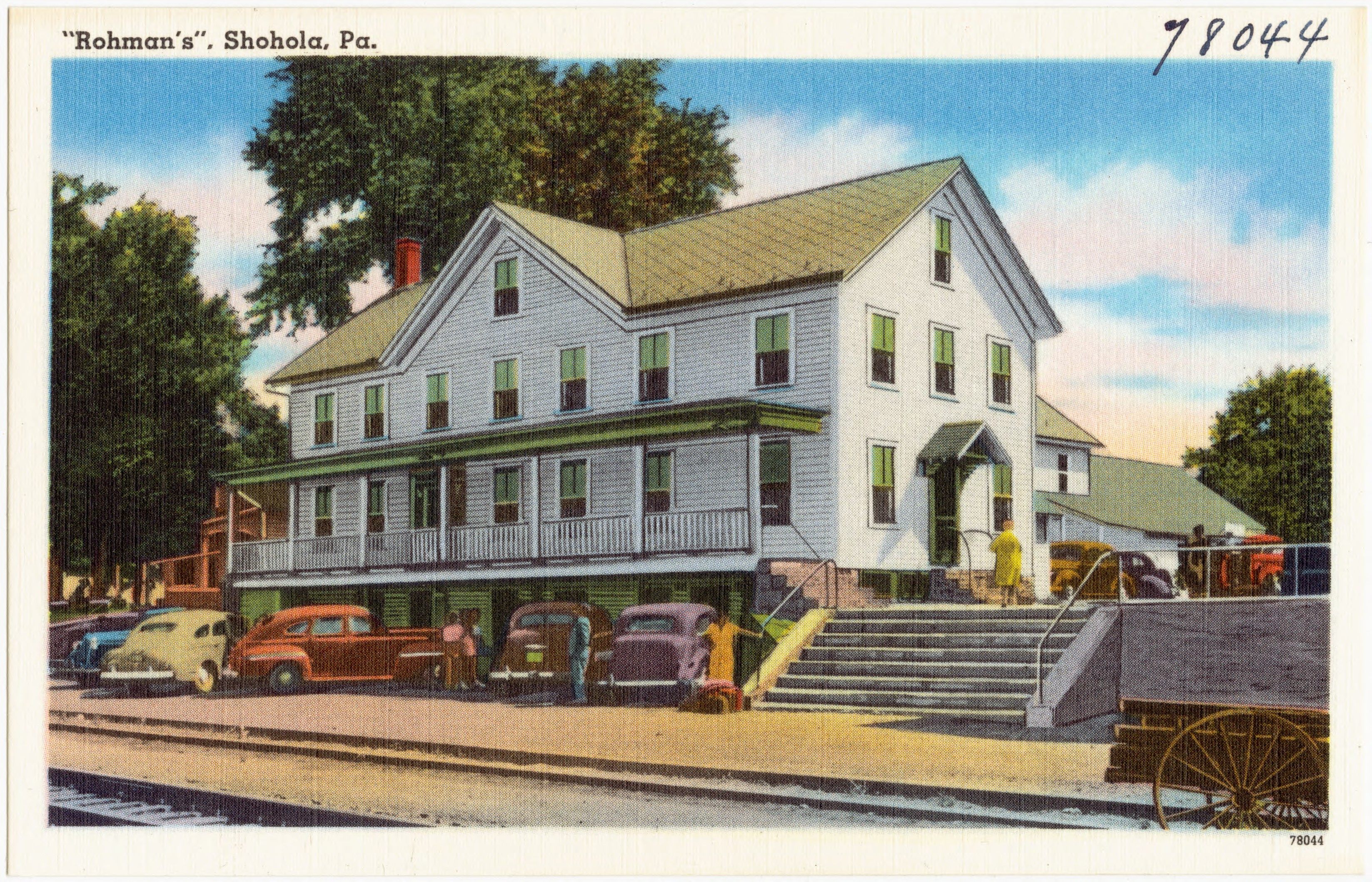

The seven-bay porch of Rohman’s Inn and Pub faces away from the rest of the unincorporated village of Shohola—its handful of homes; its post office, bank, and church; and its 25 or so other buildings. It’s as if the grand old hotel realizes how poorly it fits into this remote area in northeast Pennsylvania. Originally built in 1849, the two-and-a-half-story wood-frame building stopped functioning as an inn at least 40 years ago. But Rohman’s Pub, on the first, basement-level floor, is still a fixture for contractors and retirees who come to play pool, use the jukebox, and order freshly-squeezed screwdrivers at the 54-foot wooden Brunswick bar. “We have a good local base, anywhere from regular beer drinkers to shot drinkers,” a bartender tells me on a winter day. “Nothing too fancy schmancy.”

When the weather’s nice, the bar attracts weekend bikers from New Jersey or even New York City, 100 miles away. Some of them will rent a lane upstairs in one of the country’s most unique bowling alleys, where you have to set your own pins and follow your ball down the lane. Some will grab a beer, stand out front on Rohman Road, and smoke cigarettes all day. A placard behind the bar captures the Rohman’s spirit: “Everyone can bring happiness into this room,” it reads. “Some by coming in, others by going out.”

For more than 100 years, through different owners, iterations, and major fires, Rohman’s has somehow survived in Shohola. It was once one of dozens of hotels and boarding houses that served visitors of a long-disappeared tourist attraction called Shohola Glen, where New Yorkers came to ride the incredible Gravity Railroad and explore Hell Gate, Terror Grotto, and other natural attractions. Some of America’s most important cultural icons stayed as guests; so did survivors of a great Civil War train wreck. But today almost everything that once drew hundreds of thousands of people to Shohola is buried by forest and flood, abandoned to the elements. Only Rohman’s remains, and I was there for its 32nd Olympics.

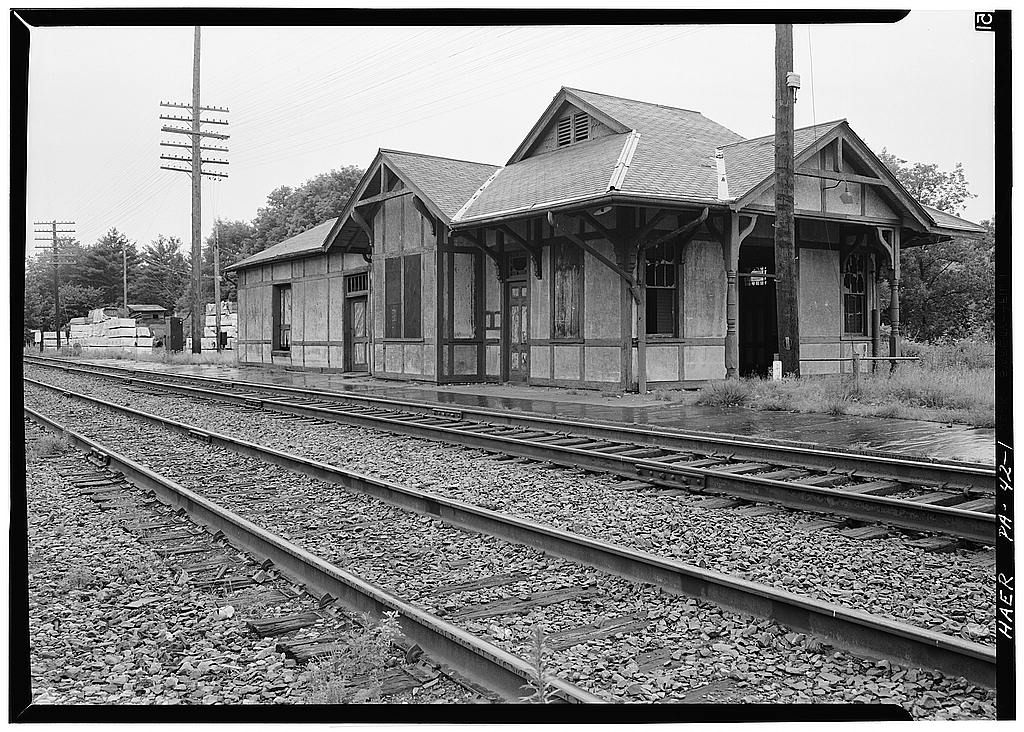

Rather than towards Shohola, Rohman’s faces New York state, the Delaware River, and, just across the street, the train tracks that once brought as many as 10,000 passengers a day to Shohola. A mile or so down those tracks, two trains crashed head-on during the Civil War in one of the worst collisions in American history. Nowadays, the tracks are where the kegs are tossed.

For the past 32 years, Rohman’s has hosted its own men’s Olympics each winter. On a recent gray and drizzly February afternoon, around 350 people assembled to watch or participate. There were many locals, but most traveled for the event. A yellow school bus showed up filled with firemen from Long Island, many of whom have been coming to Rohman’s Olympics for years. After a low-key torch lighting in which an approximately four-year-old girl declared, “Let the games begin,” the emcees announced that horseshoes and target shooting with a .22 rifle would be the day’s first events. But the first event that anyone cared about started 30 minutes later: the keg toss.

Twenty burly men stepped onto the train tracks, lifted a dented half-barrel keg weighing approximately 35 pounds, and, after a couple between-the-leg swings, tossed it overhead. The first man—wearing untied steel toe boots and a t-shirt that read, “You’re killing me, Smalls!”—threw somewhat casually. His keg landed about 15 feet behind him. Not too bad. The next man up—a skinny vet with a Harley cap—landed his keg about two ties shorter. Several competitors later, an intimidating, bald fireman from Long Island about matched Smalls. Then Bubba Fountain stepped up to the tracks.

Shohola’s first act, which established the remote woodlands as a place of interest worthy of a grand hotel, was as a rich source of natural resources. I learned this from George Fluhr, who, an hour before the Olympics started, said he wouldn’t go because of traffic.

Fluhr is both the Shohola Township and Pike County historian and a foremost expert on the area. He lives two turns and 500 feet up a steep hill from Rohman’s. During the Olympics, parking spaces run out, so people put their cars wherever the heck they want, and Fluhr didn’t want to deal with that. He’d recently had a toe amputated and was walking with a cane. “I can’t walk any distance,” he says. “I’m also very sensitive with a crowd if somebody’s going to step on my toe that’s not even there.”

Fluhr likes to tell New Yorkers that Shohola Township—in which the village of Shohola is just a tiny speck—is roughly the same size as the Bronx, the 40-square-mile New York City borough that holds about a million and a half people. “Shohola Township has 2,000,” says Fluhr, “So we’ve got lots of room.”

European settlers first came to Shohola in the 1700s because of its enormous trees. They were centuries old, four feet in diameter, a couple hundred feet high, and they covered the area. Loggers dragged the giant trunks to the river with horses and shipped them down the Delaware to be used for sailing ship masts, among other things. Workers came from New York City and sometimes straight from the immigration station at Ellis Island, and eventually they felled all the largest trees. The wood built houses between Shohola and Philadelphia and New York City. And in 1848, bluestone was discovered, and hundreds of quarries opened up. Bluestone quarried in Pike County, and adjacent Wayne County, helped construct the campuses of Princeton, Yale, and West Point. “It was the place to make a fortune,” says Fluhr.

In 1849, building off the area’s growing industry, the Erie Railroad started coming through Shohola—offering an easy way for pollution-saturated city folk to get to the fresh air of the river valley. That same year, Chauncey Thomas, a businessman with local lumber interests, built what was called the Thomas Tavern House in Shohola. Decades later, it would become known as Rohman’s. A guidebook called The Thomas Tavern House “a neat little hotel” where you could find “a clean bed and a private room.” It soon became known as the Shohola Hotel, and during the Civil War, it played an important role in a tragic train crash in 1864.

Just a mile or so from the village, an eastbound train pulling 50 coal cars met at a blind curve with a westbound Erie Railroad train carrying more than 800 captured Confederate soldiers. The first prison car, which contained 38 prisoners, was reduced to a length of only six feet—all but one soldier died. A survivor of the great prison train disaster described the terrible embrace of the two locomotives as “like giants grappling.” Overall, at least 60 prisoners, guards, and railroad staff were killed, and most were buried alongside the track in a 75-foot trench.

Shohola residents brought survivors east to the Shohola Hotel. Locals donated clothing and food, and Thomas provided shelter at the hotel, plus ham and pork shoulders. Local legend has it that one Confederate prisoner escaped after the crash, but was found dead in the attic of an unoccupied house that is still haunted by his ghost. Other stories tell of Confederate escapees shaving their beards and starting new lives near the Delaware.

When Bubba Fountain stepped onto those same tracks, at the 2018 Olympics, and took hold of the keg, it quieted the onlookers. Earlier that morning, I was told by Mary Herbert, whose mother Sheila Farrell owns Rohman’s, that Bubba usually wins every event. It was not difficult to see why. Six foot four and a deceptively lean 280 pounds (heavier than Lebron James), Bubba swung the keg expertly overhead and between his legs three times before tossing it five rungs further than anyone else would that day. Tossed it so far, a witness 70 feet down the tracks had to jump out of the way of the bouncing metal cannonball. Thus confirmed the legend of Bubba.

In 1872, under new ownership, the hotel caught fire and burned to the ground. But this seeming disaster ultimately spurred the golden age of the inn and coincided with Shohola becoming a major vacation destination.

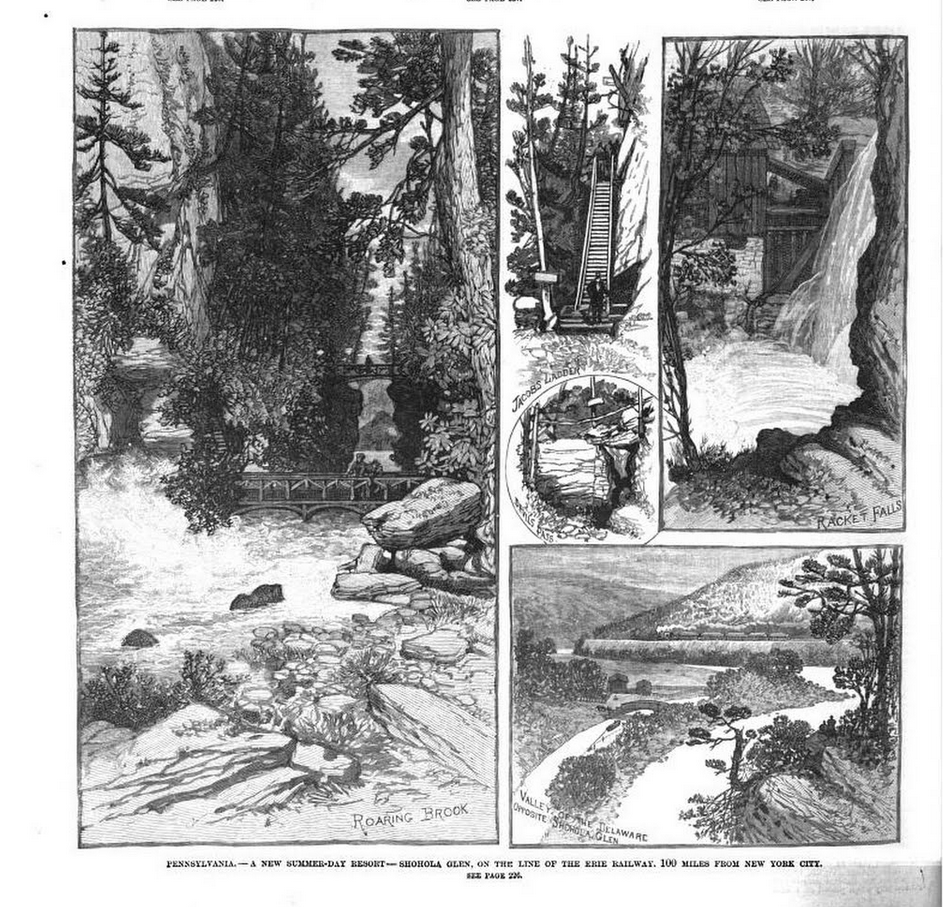

A new owner rebuilt the hotel in 1875, and then sold it to a bluestone baron named John Fletcher Kilgour 10 years later. Before his death, Chauncey Thomas had an idea to turn Shohola into a great tourist attraction. Kilgour turned Thomas’s dream into reality. He transformed Shohola into Shohola Glen and deemed it “The Queen of Summer Resorts.” At its peak, Shohola Glen drew more than 100,000 people each year, many of whom took one-dollar “excursion” trains from New York City to Shohola Station. The renamed and expanded Shohola Glen Hotel, which held 50 guests, was just one of dozens of hotels and boarding houses serving overnight guests for $4 to $7 a week.

The Glen took advantage of the area’s natural beauty. Kilgour built walking paths, scenic overlooks, and romantic seclusions with names like “Fairy Bower” and “Solitude Rest.” There was “Lover’s Walk” for couples and a wishing pond called “Wood Nymph Grotto.” Natural formations were given dark titles like “Satan’s Nose” and the “Spirit of Dark Waters.” Underneath a railroad bridge, Kilgour built a roller rink and dancing platform, and refreshment stands sold frankfurters and soda. The Glen also had a merry-go-round, picnic areas, and a natural bathhouse. Five cents bought a ride on a water-powered switchback Gravity Railroad, an early thrill ride and precursor to the roller coaster.

In 1907, the Erie stopped the inexpensive trains to Shohola, which spelled the end of the Glen, too. A lumbering operation bought the land, and the attractions were ignored. In 1955, Hurricane Diane caused massive flooding that buried or destroyed much of what remained of the amusement park. Fluhr says a few archaeological remnants of the Glen can be found by those in the know and willing to trespass. In 1997, Fluhr helped get Rohman’s into the National Register of Historic Places. The application states that the building “is all that remains of the busiest tourist destination that ever operated in the Upper Delaware Valley.”

One of the stranger Olympic events at Rohman’s is called Polish skiing. As the crowd watches, four men tied by their feet to a single pair of wooden planks coordinate around a corner. Surprisingly, I didn’t witness any major spills.

“We’re not supposed to call it Polish skiing, to be politically correct,” says Sheila Farrell, the 72-year-old owner. When I ask where it originated, Farrell says, “Somebody told us about it. Probably somebody from Scranton, where they have all the Polacks.”

There’s also the bed race, in which four men push a wheeled, iron-framed bed complete with a mattress and supine teammate. Women help judge the cooking contests, but don’t compete. (A younger patron tells me she once secretly signed up for an event, but another woman ratted on her. Farrell says they’ve tried to hold a women’s Olympics, but it’s never worked out.)

Although Rohman’s unorthodox games began several decades ago, their spiritual origins are the next stage in Rohman’s history. It’s unclear exactly how he raised the money at age 22, but in 1909, a local named Arthur Rohman bought the hotel, renamed it after himself, and kept it alive through pure force of personality.

Rohman ran the inn for 64 years—through Prohibition, the Great Depression, another fire in 1941, the rise of the automobile, and two world wars—and he was no ordinary innkeep. George Fluhr knew Rohman and says he rarely left the building. He lived upstairs, came down to the bar first thing in the morning, and left when the last customer did. “He was a landmark himself,” says Fluhr. Rohman’s first patrons were lumberjacks and stonecutters, but over the decades, transitioned to farmers, fishermen, hunters, and, finally, curiosity seekers. When a writer in 1964 visited the bar, he asked Rohman how he kept the place afloat. Rohman said: “You have to have some identity.”

The bar molded itself around Art Rohman’s eccentricities. When the Pennsylvania liquor board insisted that a bar must have seats, Rohman installed 13 hinged, pull-down railroad engineers’ stools on his hand-carved bar because his customers liked to stand. (The stools are still there, but the springs are wonky.) His clientele were geographically diverse, so he collected phonebooks. They piled up until it became tradition for customers to bring new ones. Though the holidays were popular with customers, Rohman never allowed a Christmas tree after his wife died on Christmas Eve in 1933. In 1970, a writer for the Sunday Record declared Rohman’s an institution and a landmark. The writer asked an 83-year-old Rohman if he would ever sell. “Never,” he said. “I need to be occupied.”

Rohman smoked 12 to 15 cigars a day, according to one customer who called that estimate “conservative.” Every time Fluhr went in, Rohman gave him a cigar, even though Fluhr didn’t smoke. He did the same with everyone. After Rohman died in 1973, the cigar salesman came to ask why his products didn’t seem to sell anymore. “They were never sold,” says Fluhr. “They were always given away.”

Passenger trains stopped arriving in Shohola altogether in the 1960s. But Rohman’s remained even after Art Rohman died. In the mid-1980s, Sheila Farrell and her siblings purchased the building; today Farrell owns it along with a business partner. Though the phone books are gone, a collection of patches begun by Art Rohman—first from WWII veterans, and now from police and fire stations—still hangs behind the bar. On the far wall hangs a plaque that a local Lions Club dedicated in honor of the inn’s role helping victims of that great prison train wreck.

If you ask to see “the scrapbook,” you’ll be handed “The Story of Rohman’s,” which Fluhr put together. The book contains copies of articles going back decades. They describe the famous people who have been to Rohman’s, including writer Zane Grey, boxers Jim Stewart and Jack Britton, and actors Mary Pickford, Bette Davis, Jean Harlow, and Paul Newman. Smokey Joe Wood, who went 34-5 in 1912 for the Red Sox, lived in the area and brought his friend Babe Ruth. Other articles show Art Rohman towards the end of his life and as a schoolboy, and the old Shohola train station (where the lumber supply now sits).

The scrapbook also includes a rendering of the Shohola Glen Hotel in its heyday—think men with canes and top hats and all—and copies from the old hotel register. One page stands out: In November 1927, the book was signed by Gertrude Ederle, the first woman to swim across the English Channel. Just below her name is Ruth Elder, the female aviation pioneer. And, just six months after flying the Spirit of St. Louis across the Atlantic, Charles Lindbergh signed the book, putting his address as the “Entire World.”

During the Olympics, the beer pong tournament showcases Rohman’s most unforgettable feature. On the second floor, in what used to be an enormous dining room, Art Rohman built a four-lane bowling alley in 1941. There is nothing mechanical in the room (aside from an old jukebox that plays at whatever volume it feels like). Nobody even works the upstairs. You pay an hourly fee at the bar and the alley is yours. After sending your ball down a lane, you have to walk the same path to reset the pins and send your ball back via a gravity-driven pair of rails. After a couple games, your legs have gotten a good workout. Decades back, children earned a few cents working as pin-setters. Nowadays, the few children willing to set pins get five dollars an hour.

Bubba Fountain, a pipeline technician, didn’t participate in most events in 2018. But in years past, he won two-man saw, the turkey shoot, the bed race, and the-event-that-isn’t-supposed-to-be-called Polish skiing. He says he wanted to give others a chance to win this year. But a couple hours after winning the keg toss, he decided to win the triathlon, too, which meant hitting a target with a .22 rifle and bow and arrow, and then chugging a 32-ounce beer. Afterward, Bubba wore his medals proudly and took home a snowboard and a Yuengling umbrella as prizes. “Great people come here. Great owners, great people. It’s just a good time,” he says. “I don’t really go out to the bar much, but if I do, I come here.”

The Olympics ended with little drama, transitioning into a regular night at the bar. The emcees shouted less and less decipherably from the second-level porch, and nightfall came to Shohola. The crowd thinned until everyone but the smokers escaped the cold rain inside Rohman’s Pub. Steve the bartender served drinks to a crowd of locals that all knew each other, and the last of the Shohola Glen hotels—where masters of the sky and screen once drank alongside loggers and stonecutters, and where Civil War soldiers healed—carried on for another night.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook