What Does It Take to Be the Rolley Hole Champion?

Marbles is a serious game in Overton County, Tennessee.

Cradling his marble, Kenzie Adams knelt in the dirt yard and sized up the distance he needed to cover. For over sixteen hours in mid-September 2021, sixteen teams had battled in the 38th National Rolley Hole Marbles Championship in Overton County, Tennessee. The championship title now rested solely on the play at this last hole. It was past midnight; the day’s festival goers were long gone leaving a few devoted fans to watch under Standing Stone State Park’s wooden pavilion. As the cool darkness of the night enveloped the yard, the chirping of crickets and the hushed yawns of steadfast onlookers replaced the day’s music and laughter.

Adams didn’t seem to notice this shift. He and his partner, Andrew Walker, were riveted on this final game and the maneuvers of their opponents, Larry Denton and Saylor Walden. These four silently reacted to each other’s progress—crouching or standing in turns as if choreographed. Every now and then one of them stuck their foot out suggesting to their partner where they should aim their next shot.

The game of rolley hole doesn’t reveal itself all at once. A casual observer will first notice the hallmarks that distinguish it from the world’s innumerable marble games: its specially designed playing yard and distinct rules. On a dirt 40-foot-by-25-foot yard divided lengthwise by three tiny holes, a pair of players face off against another team of two. Armed with one marble each, each player’s goal is to sink his marble in each hole in a certain pattern for a total of 12 holes. The team that completes this first wins. The players alternate turns and can take another shot if they hit an opponent’s marble or get their marble in a hole.

The simplicity is deceiving. Within the players’ silent rhythm lies the strategy at the heart of the game. To successfully plot a path to victory, players must switch between defense and offense, working to get their marble in each hole and prevent their opponents from doing the same all while anticipating their opponents’ future moves. Adams asks himself, “well, what’s their shooting range? If I put it right here, will they shoot? Will they hit? If I put it right here, will they miss?” He sums it up simply: “It’s kind of like a cat and mouse. I’m going to tempt you; you’re going to tempt me.”

While many of the competitors have played rolley hole for their entire lives, Adams, a history buff and former undertaker, has only been playing for a few years. Adams, 30, and Walker, 27, began playing for fun after days spent building fences; their fathers and grandfathers also played together. They regularly practiced throughout the night leaving the marble yard in the early morning to get a few hours of sleep before work. Adams even studied videos of old competitions and learned as much as he could from the game’s greats.

He has plenty of experts to consult. Rolley hole has prospered for generations around this stretch of the Tennessee and Kentucky state line, an area of farmland and small communities almost a two-hour drive northeast from Nashville. While its exact origins are unknown, rolley hole may have derived from ancient Native American, British, or French marble games, and it has survived in the region thanks to players who have passed down their knowledge of the game to the next generation of competitors.

Rolley hole devotees have also passed down the skills needed to make the marbles that are essential to the game. Store-bought glass marbles can’t withstand the force of collision in competition play, so artisans craft rolley hole marbles from flint found in local creeks and streams or sometimes from agate. Unlike the typical clear commercial marbles swirled with color, rolley hole marbles are opaque and earth toned. The marble Adams used in the championship, which he made himself, is a quintessential example: its subtly varied shades of white make it look like a perfect full moon in miniature.

The National Rolley Hole Championship began at a time when the future of rolley hole was in jeopardy despite its deep roots in the area. In the early 1980s, as organized local sports and other entertainment activities grew in popularity, the number of marble yards in the region had dwindled to one in Kentucky and one in Tennessee. At the time, Ranger Bob Fulcher, now a park manager at Justin P. Wilson Cumberland Trail State Scenic Trail State Park, was a regional interpreter for the Tennessee State Parks charged with creating programming for the public. In 1983, he organized the Standing Stone tournament to preserve the tradition. Of the tournament’s designation as a “national” championship, Fulcher says, “I use that name as a bit of tongue in cheek hyperbole.” He never expected people to travel from out of state to compete.

Now, almost 40 years later, Ranger Shawn Hughes is the one in charge of organizing the tournament. Each year he tries to entice rolley hole players from other states to enter, but they know local players dominate the marble yard; every winner has been from Kentucky or Tennessee. Hughes is a local, too. He grew up eight miles from Standing Stone and was first introduced to rolley hole in the early 1990s when he worked at the park as a teenager. One of his jobs was to scrub the stone border of the marble yard. Hughes is a proud caretaker of the tournament; he understood fans’ disappointment when they learned the pandemic forced the cancelation of the 2020 competition. He remembers, “They said, ‘Shawn, you don’t know how important that tournament is’…for them to tell me that they knew how important it was was really neat. Because I think it is.”

Around the marble yard at the 38th National Rolley Hole Marbles Championship that love of tradition surrounded the competitors. Loyal fans who refused to go home until the last hole was played lined the yard. Above their heads, nailed to the pavilion’s rafters, were plaques bearing the names of every tournament winner.

Adams and Walker were on the verge of earning their own plaque and $800 in first-place prize money. The teams had been neck and neck throughout the final making their holes at the same pace. With one hole remaining, it was anybody’s game; the first pair to sink their marbles would win. Walker had already “rolled out.” He and Adams were halfway towards victory. If Adams made this shot, they would take the championship.

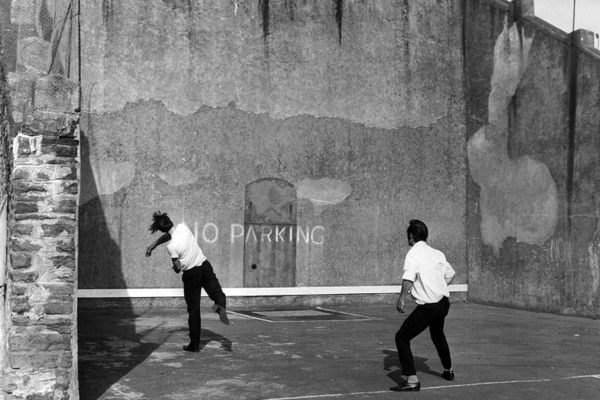

![At the 38th National Rolley Hole Marbles Championship in 2021, 16 teams competed for more than 16 hours before Adams and his partner, Andrew Walker [right], made it to the final round.](https://img.atlasobscura.com/E-ZeriHFl3zLrTqAKQMH1dEHPKVN0pdiBpgL7biy-rE/rt:fill/w:1200/el:1/q:81/sm:1/scp:1/ar:1/aHR0cHM6Ly9hdGxh/cy1kZXYuczMuYW1h/em9uYXdzLmNvbS91/cGxvYWRzL2Fzc2V0/cy85MmQxYzdiYi01/NGExLTRkNjctYjg5/Ni1lZGU2ZWZjNGM5/NTdlMTJkNWJlNmQz/ZGZiMWJkMDdfMjAy/MSBtYXJibGVzIGNo/YW1waW9uc2hpcC1y/b2xsZXktaG9sZV84/MTlfNDkucG5n.png)

Like a pool player chalking his cue, Adams stretched out his palm and swiped it through the tan dirt, taken from a local riverbank and sifted and pounded to a fine powder. With a flick of his thumb, he sent his marble flying towards the hole. He missed.

It was Walden’s turn, and he effortlessly knocked Adams’s marble clear out of bounds. Because he hit Adams’ marble, Walden could take another shot. He easily rolled his marble “within span,” a position where the marble is so close to the hole that the player’s hand can stretch between the two points. In this spot, he would be allowed to simply pick up the marble and drop it into the hole on his next turn.

Next Larry Denton crouched down to shoot. Seventy years old, Denton began playing rolley hole in high school. Even though he lived a couple hours away from Standing Stone, he used to regularly drive to this area to get to a yard where he could practice. His dedication paid off; he won the tournament in 2013 and 2014. He reminisced about his win. “I had to shed a little tear that night.” For him, “this is the tournament of all tournaments.” And he was close to victory again. He hit his marble to join his partner’s within span. If Adams missed his next shot, Denton and Walden would be the 2021 champions.

Adams knelt on the edge of the yard, about ten feet from the hole and his opponents’ marbles. His best bet was to hit one of his opponent’s marbles in order to get a second shot to get near the hole.

A great player must be able to “manage,” or control, his marble on the yard. He must be able to shoot his marble in straight lines, but he also needs the skill to make it stop where he wants it. For this shot, Adams would need to “settle” his marble—that is, spin the marble in such a way that it takes the spot of the marble it hits. With a snap of his thumb, Adams sent the marble speeding toward Walden’s as if the two were connected by a wire. It hit and settled, the crack of the marbles colliding declaring his success.

Adams got to shoot again. He needed to glance off Denton’s marble, which would put him within span and give him another turn to put his marble in the hole. If he hit Walden’s again, he would be “dead”; there is no extra turn for hitting the same marble twice. He’d have to wait for his opponents to take their turns before he could take another, and he couldn’t afford to give them the chance to knock him away from the hole. He fired his marble over the inches separating it from Denton’s marble. It was a perfect shot, hitting his opponent and landing within span. To the applause of the invigorated crowd, Adams quietly picked up his marble and placed it in the hole, clinching the championship.

For Adams, “it was a complete shock.” He says, “you kindly want to pay your dues, so to speak, and, you know, three or four years of playing, you just don’t think you’re going to win something like that, and it was just truly amazing.”

Now Adams will have to decide what to do with the marble he used in the final. It’s too special to play with anymore. He might take another cue from past rolley hole players: maybe one day he’ll give it to Walker’s young son. He says, “we have generational marbles, and I like the idea of keeping up with that sort of tradition.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook