The Saga of a Long-Lost 15th-Century Illuminated Prayer Book

The Luneborch manuscript vanished, and was lost for decades only to reappear again in a mysterious package.

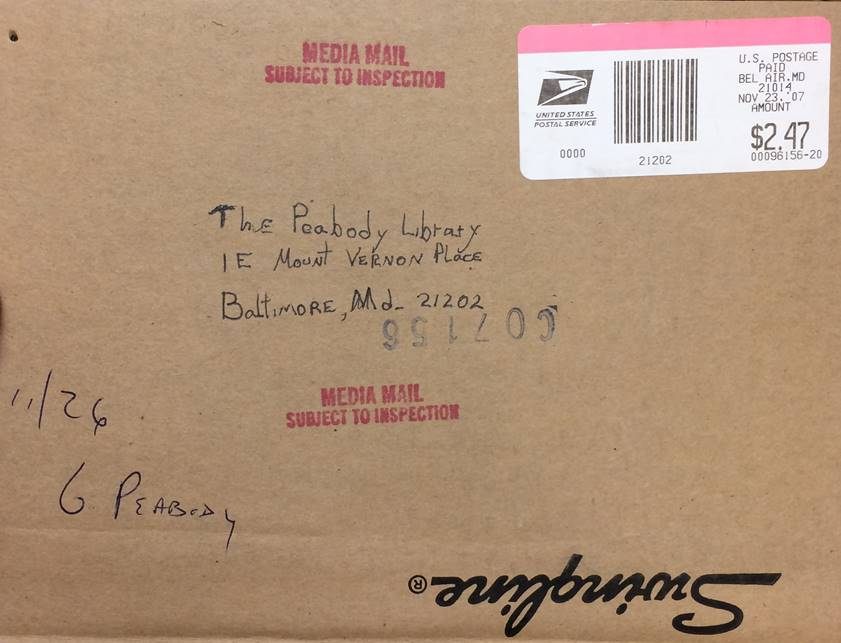

One day in 2012, Paul Espinosa, the rare books assistant at the George Peabody Library at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, opened a package that had been delivered to the library’s mailbox. Inside was a long-lost 15th-century illuminated prayer book.

The manuscript is one of the rare examples of vernacular spirituality—meaning it was for personal use, not in a church—from early Renaissance Germany. Known as the Prayer Book of Hans Luneborch, in Low German, for the man who had commissioned it in 1492, the book had been donated to the Peabody in 1909 by Michael Jenkins, a Baltimore railway and banking magnate and avid European art collector. But sometime between then and the 1970s it had disappeared. Many academics attempted to locate the book, but James Marrow, now Professor Emeritus of Northern Renaissance Art at Princeton University, led the hunt.

In 1962 Marrow, then a graduate student at Columbia University, was researching Dutch illuminated manuscripts and was combing through the Census of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts in the United States and Canada, published in the late 1930s. According to the census, the Luneborch Prayer Book, containing 44 illuminated pages, was at the Peabody.

“Forty-four illuminations is an extraordinary number for a book dating from that period, and the fact that it was written in ‘Low German’ got me wondering if it wasn’t a Dutch manuscript,” Marrow says, because 15th-century Dutch writing was sometimes catalogued as “Low German.” “I was really curious to take a look at it myself and find out.”

He reached out to the Peabody, but they couldn’t locate the manuscript. For the next 10 years, Marrow went on with his research, and kept looking for the Luneborch. In the late 1960s, he studied with Dorothy Miner, a curator at the Walters Art Museum, across the road from the Peabody. “Oh dear,” he remembers her saying, “that manuscript is missing and nobody can find it.”

By 1970, after a few more inquiries from academics, the Peabody wrote off the Luneborch manuscript as “lost.” Marrow thinks it had been stolen. “Maybe by someone who knew the premises, someone who worked there,” he says. “In my experience with archives that is what usually happens. But we don’t know for sure.”

And that is the way it stayed for 40 years, until Espinosa opened a package, postmarked “Bel Air, Md.” and addressed to the Peabody, but without a return address. Marrow’s operating theory is that someone from the thief’s family found it and decided to return it to its rightful place. “That is an option, but again we don’t know. What’s weird is that for 40 years there is no record of anyone trying to sell the book.”

Stacey Lambrow, an intern who was working at the Peabody at the time, was put in charge of finding out more about the box’s contents, since it wasn’t clear just what manuscript it contained at first. Suspecting it could be the Luneborch, she turned to Marrow, and shared a few scanned pages.

“I recall looking at the scans and going, ‘Wow.’ That was the Luneborch Prayer Book,” he says. “But not only that. Its gorgeous illuminations were made by a Dutch artist that I knew really well, so in a way I was half-right, it was kind of Dutch after all.”

The Dutch artists in questions are known the Masters of Dark Eyes, one of the most prolific groups of illuminators from Renaissance Holland, known for the dark, heavy shadows round the eyes of their figures. “What comes out of it is the sense of individual psychological presence within the individual faces of the characters, which is a rather innovative and difficult to achieve effect,” says Earle Havens, Nancy H. Hall Curator of Rare Books and Manuscripts at John Hopkins. Havens selected the Luneborch manuscript as part of Bibliomania, an exhibition on rare books currently at the Peabody.

As a student of Northern European Renaissance, Marrow has traveled extensively through the region, and knew the exact place where the manuscript came from: Lübeck, in northern Germany, which in the 15th century was the most important harbor of the Hanseatic League, a trading bloc that stretched from the Baltic to the North Sea.

So beyond its indisputable value as a work of art, the book indicates that a German, Hans Luneborch, had appointed a Dutch master to illustrate his personal prayer book, which was news to art historians. “At the time, German and and Dutch cities were competing, and so far we did not have much evidence of illumination art trade between them,” Marrow says. Even though Lübeck was the most important trading harbor at the time, more important than Amsterdam, the Dutch still claimed primacy over illuminations.

Marrow, with an expert in Low German and a local historian from Lübeck, is now tracking the rest of the manuscript’s history. Though it was probably in family hands, most of it’s earlier history is as much a mystery as its whereabouts for most of the 20th century. “What’s amazing about this manuscript, beyond the fact that it dates from 500 years back, is that it had such a unique history,” says Marrow. “It was found and then lost and eventually turned up in the right place at the right time.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook