Salem and the Rise of Witch Kitsch

How Salem went from executing witches to marketing them.

Stroll through the downtown of Salem, Massachusetts, and you’ll quickly run into the city’s most contentious piece of public art. Nine feet tall, made of polished bronze, and planted right in the middle of a central town green, the scandalous statue is all but impossible to avoid. Perched on a broomstick and backed by a crescent moon, it depicts Samantha Stephens, the nose-twitching heroine of the hit 1960s TV show Bewitched.

The statue went up in the spring of 2005, sponsored by cable station TV Land and approved by the city government. Some residents, thinking of another of the city’s scandals, were peeved. “We’re right near the courthouse where people were tried for witchcraft,” resident Jean Harrison told NPR. “Having a kitschy statue just seems to trivialize what these people went through.”

Stanley Usovicz, the mayor at the time, was insistent. “This city has long recognized the true tragedy of 1692,” he replied. “But I think we also have to recognize that there is a popular culture, and that we are a part of that popular culture.”

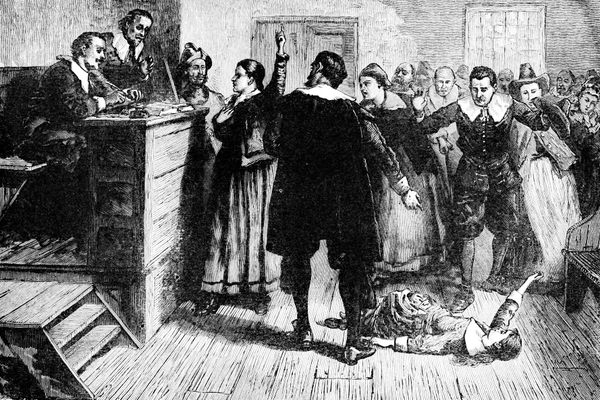

In 1692, 185 people were accused of witchcraft in Salem. Over the course of nine paranoid months, 19 of them were executed. On a rainy October Friday in 2016, Salem is filled, once again, with supposed witches—this time in the form of tourists, their pointed hats catching on their umbrellas. They file in and out of witch-themed tchotchke shops, get their cards read by local psychics, and grab cones at the local ice cream parlor, the Dairy Witch. Somehow, between the 17th century and now, Salem and its fans conjured up a new meaning for a historic tragedy, transforming it into an infinite set of tourism opportunities. How did this city bewitch itself? And what does it mean for those of us who find ourselves there?

If you take a long view of history, Salem’s witch trials were far from unique. Between the 13th and 18th centuries, tens of thousands of accused witches were killed in Europe, and hundreds more in the American colonies. For some reason, though, everyone has always wanted to learn about theirs in particular. “Witch tourism [in Salem] goes back to almost the second the bodies were taken down,” says J.W. Ocker, author of A Season With the Witch: The Magic and Mayhem of Halloween in Salem, Massachusetts. “For some reason, this one stuck with everybody.”

As Ocker details in his book, Salem has had plenty of opportunities to shake this association. In the centuries following the trials, it was a Revolutionary War ground, a bustling maritime port, and a manufacturing hub, full of tanneries and steam cotton factories. It’s the birthplace of Nathaniel Hawthorne, the National Guard, and Monopoly. But even as the city’s purposes shifted, the witches stuck around. In 1891, a jeweler named Daniel Lews began crafting intricate witch-themed silver spoons, selling thousands and sparking a nationwide decorative-spoon trend. Even at the House of Seven Gables, which you’d think would spend its time hawking Hawthorne, “they would hand-paint witches on glassware and sell them,” says Ocker. “It’s always been there to some degree.”

By the beginning of the 20th century, some of these identities were fading. The economy was changing, and there was less need for American-made leather and cotton. Boston and New York were suddenly overshadowing Salem’s relatively small port. Witch enthusiasm, however, had not dimmed. “Manufacturing died there, like it did in so many American cities,” says Ocker. “They had nothing to fall back on but witch tourism.”

As you pull into Salem, one thing is immediately clear: The city has really leaned into this new branding. The Salem High School mascot is a witch, with huge green eyes and warts to match. Another flies over the masthead of the local newspaper. City police wear patches that say “The Witch City, Massachusetts,” complete with a big-hatted specimen. This past March, they were accused of Freudian slippage when they asked the community to “Please remove cats from school lots.” (They meant “cars.”)

In October, even more witches fly over the city, emblazoned on banners for “Haunted Happenings,” a monthlong festival that transforms the downtown into a spooky smorgasbord. As I walk through, facepaint artists are turning tourists into vampires, and a side street has been taken over by something called the “Electric Ghost Electronica Festival.” A small carnival is closed due to weather, and the Ferris wheel drips rain on passers-by. A brochure reveals all the things I missed earlier in the month: regular evening seances, visits from various horror movies stars, and the opening day “Zombie Walk,” which culminates in a game of undead kickball.

Haunted Happenings, which is the city’s biggest purveyor of creepiness, took off in response to something legitimately scary. In September of 1982, a still-unknown criminal took bottles of Tylenol off of shelves in drugstores around Chicago, filled them with cyanide capsules, and replaced them, killing seven people. The murders reverberated across the country. Frightened parents angled to keep their kids inside on Halloween, and many communities banned trick-or-treating all together. When Susannah Stuart, then the head of the Salem Witch Museum, proposed replacing the traditional DIY festivities with a weekend-long official bash, the city quickly got on board.

People outside of Salem were enthused, too—the first Haunted Happenings attracted around 50,000 tourists, effectively doubling the city’s population for the weekend. Its success paved the way for more and more Happenings. “It began as a way to help kids have a safe Halloween,” says Kate Fox, “but it quickly became apparent to the people in charge that it was also a way to extend the tourism season past Labor Day.” Fox is the executive director of Destination Salem, the tourism bureau that pulls together the many organizations, companies, and individuals that make the various Happenings possible. Cozy in her downtown office, she’s wearing a black jacket and an orange scarf, which she puts on to look festive for the TV broadcasts.

At this point, Haunted Happenings has hundreds of contributors. They come from many different sectors of the community, and they take on the witch thing from all angles. There are the historians, who host lectures, town tours, and educational plays. There are the freakout fans and pop culture aficionados, who contribute costume contests and scary movie screenings. There are the actual Wiccans, who flocked to Salem after influential pagan priestess Laurie Cabot moved there in 1970. They throw a monthlong “Psychic Fair and Witchcraft Expo” in the mall, along with a number of glamorous witch parties. “They all have to coexist on parallel planes,” says Fox.

Over the years and under this pressure, Haunted Happenings has stretched and stretched, like a thief on a medieval rack. When Fox started at Destination Salem, in 1998, it was about two weeks long. Now it lasts the entire month. On October weekends, the Massachusetts Bay Transit Authority runs extra trains to and from Salem. In some ways, Haunted Happenings seems like a textbook example of holiday creep—the same phenomenon that decks malls in Christmas ivy before school has started, and sends pumpkin spice wafting through the July air. “September definitely begins to feel October-ish,” says Fox. “People in Salem see Halloween stuff out in August and say, ‘Not yet!’”

But the city isn’t entirely to blame—they’re just the irresistible flame, holding steady for all of us confused moths. “People come in off the train from all over, come up to the visitor’s desk, and say ‘What should I do?’” says Fox. “And you have to say, ‘Well, why are you here?’” And they say, ‘It’s October. I just felt like I should come to Salem.’”

A lot of people who aren’t quite sure why they’re in Salem eventually find themselves at 310 ½ Essex Street. Tucked between the Historic Salem headquarters and an ordinary residence, the so-called “Witch House” is the only building still standing that actually played a role in the 1692 trials. On Friday, an attendant ushered damp participants down the paved path and into the black clapboard building, where they paid $8.25 to see choice bits of history arrayed to tell a particular story.

The Witch House was once home to Judge Jonathan Corwin, a merchant and politician who held great standing within the community. After being appointed to a sort of witchcraft investigation committee, Corwin heard testimony from three different accused women, potentially in that very house. This came across almost immediately—as you walk into the Witch House kitchen, the first thing you see is a long trestle table, covered end to end with photocopied testimonials from the trials. In later rooms, everyday 17th century objects, like spinning wheels and rope beds, intermingle with spookier artifacts.

Some of these are intimately related to the trials—there’s a “poppet” doll similar to those found in the home of witch hunt victim Bridget Bishop, and used as evidence in her conviction. Others—like a display themed around corpse medicine, and a vial of “Winthrop’s Black Powder” made from smushed toads—seem to be there simply because they’re creepy. Even with all the horrors of the 17th century arrayed before us, though, the trials stand out, and two young guests peer at a plaque with more printed testimony and ask the question on everyone’s minds: How did this happen?

Elizabeth Peterson, the museum’s director, offers up thoughtful, nuanced answers about mass panic and historical context. “I wish we could just say it was ergot,” she says, referring to a theory that a hallucinogenic fungus caused it all.

People have long had questions about the Witch House, and there has almost always been someone to answer them, for a price. After later generations of the Corwin family let go of the building, in 1856, it was purchased by an entrepreneur named George Farrington. Farrington turned much of the house into an apothecary, with boarding rooms on the second floor. Along with his medicines and tinctures, he marketed the house’s history, selling his wares in bottles emblazoned with a small witch on a broomstick and charging patrons extra to take a peek at what had been Corwin’s kitchen. He also made postcards and stereoscopic inserts, establishing what he had begun calling the “Old Witch House” as a spot worth seeing. People began coming to Salem just to visit it.

The building went through many incarnations—soda fountain, umbrella repair shop—but the shifting proprietors “always charged five cents to see the judge’s staircase and fireplace,” says Peterson. In that way, they kept its reputation as a historic tourist site alive. In 1944, the building was threatened by widening roads, and the city of Salem bought it in order to save it, transforming it into a museum and officially naming it the Witch House.

As a community leader and historical expert, Peterson is often called upon to vet the appropriateness of the world’s many attempts to dramatize her city. When she weighed in on the WGN show Salem, in which actual supernatural witches live alongside Salem’s accused innocents, she argued that the show could do little harm, because it’s so obviously fantastical.

The Witch House is, in many ways, Salem’s most truly historic site. But its name is also a bit fantastical, in that it housed zero witches. Peterson and other concerned parties have been lobbying to change it to the less zingy but more accurate “Corwin House.” “We’ve tried to rename it for years, through the tenures of three mayors,” she says. “They’ve disapproved every time.” The brand is just too strong.

As the day grays into black, my companions and I explore more of the city’s themed offerings. We hit up the Witch Museum and the nearby (and confusingly similar) Witch History Museum, both of which present the story of the trials as a series of lit-up wax tableaus. We tour the cauldron-heavy sets of WitchPix, in which, for $34.99, you and your friends can dress up in long furs and pointy hats and be photographed posing around a cauldron. We opt for a cheaper option—sticking our heads into plywood cutouts that offer up scenes of happy, dancing witches.

This strange brew of voyeurism and role-playing serves to separate the two meanings of “witch” that Salem has on offer. It’s sobering to watch people (even wax people) get ostracized, tried and executed for crimes they couldn’t possibly have committed. It’s fun and wacky to pretend to be a glamorous lady with a pointy hat and actual magic powers. Before we depart, we find ourselves in HausWitch: a high-ceilinged, softly lit retail space that offers tarot decks, “Witch City” tote bags, and affordable spell kits for your home.

HausWitch is capitalizing on another burgeoning trend—that of the chic, modern-day Tumblr witch, steeped in feminism and self-care. Its couches are covered with moon-shaped pillows, and its tables are strewn with incense bundles. Advertisements for in-store yoga hang alongside silkscreened “Womyn” posters and plump succulents. My impulse is to consider it the nadir of Salem’s commercialization: tourists coming to Witch City and leaving with a bunch of $12 magic rocks.

But even as I take snarky notes, something undeniable slowly occurs to me: it feels good to be there. Teenage girls are bustling in and out, tasting herbal tinctures and giggling and waving around bundles of sage. As I smell candle after candle and watch my friends pose with various geodes, the tension of the day’s contradictory narratives starts to dissipate. I think of something Kate Fox said, back in the tourism board office: “Having this penetration into someone’s psyche is a heavy burden for the community.” The heaviness goes both ways, and it’s nice to spend a little time with some crystals.

HausWitch is also notable for its newness. It’s more of a piece with other parts of Salem’s culture—the burgeoning restaurant scene, the growing Peabody Essex Museum, which is now the ninth largest art museum in the country. The current draw of witches dovetails with the historic one, setting Salem apart for positive reasons. ”It’s a mutual, symbiotic relationship,” says Ocker. ”If it weren’t for the fact that everyone wanted to come to Salem on Halloween and party, the town would be forgotten.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook