The Story of Sam Patch, America’s First Professional Waterfall Jumper

Patch had a fondness for plunging into the abyss—in front of a paying audience.

An 1850s man and woman in front of Niagara Falls, where Sam Patch performed two death-defying leaps. (Photo: Public Domain)

There were myriad ways to become famous in 19th-century America, most of them involving fighting in a war, or rising to the top of the political ranks. For Sam Patch, the nation’s first professional daredevil, the path to celebrity was full of reckless plunges and booming splashes, occasionally accompanied by a bear. This is the story of a great waterfall jumper and his final leap into an unforgiving abyss.

Born around 1807, Sam Patch grew up in Pawtucket, Rhode Island. As a boy he worked as a spinner in a cotton mill above Pawtucket Falls. This formidable torrent of water, said Rochester’s Democrat and Chronicle in 1897, was “what coaxed Sam to go into the leaping business.”

Patch and his fellow young mill workers began jumping from a bridge into the Blackstone River, to amuse themselves and impress each other. Patch had a particular aptitude for elegant leaps, and sought ever-higher platforms from which to hurl himself into the water. The Democrat and Chronicle said he ”developed as a leaper in a wonderful way, few of the boys caring to duplicate his feats.”

As an adult, Patch moved to work in a cotton mill in Paterson, New Jersey, where he stepped up his leaping efforts. In September 1827 a new bridge was being installed on a ledge over the Passaic Falls, at a height of some 80 feet above the water. Capitalizing on the public’s interest in watching the pre-constructed bridge being plonked onto the ledge, Patch appeared before the crowd wearing just a shirt and underwear. He hurled himself from the ledge, hit the river feet-first with an almighty splash, and emerged a local celebrity.

After a few more jumps from the same spot—always in front of a crowd—greater heights and tougher challenges beckoned. Patch settled on the Holy Grail for a northeastern waterfall leaper: Niagara Falls. On October 7, 1829, he leapt from a platform on Goat Island, which divides the two sets of falls on the American side from Horseshoe Falls on the Canadian side.

New York’s Evening Post reported that he “walked out clad in white, and with great deliberation put his hands close to his side and jumped from the platform into the midst of that vast gulf of foaming waters from which none of human kind had ever before emerged in life.”

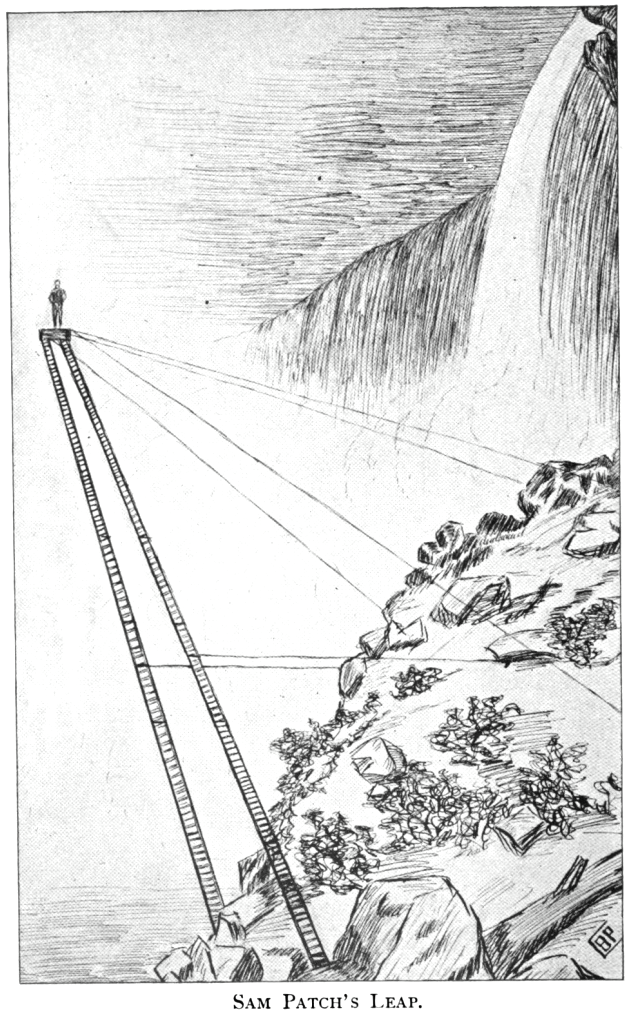

The ladders and platform built for Patch’s second Niagara Falls jump. (Image: Public Domain)

Ten days later, Patch flung himself into the Niagara abyss once more, this time from a higher platform, built on top of two ladders on a cliff below Goat Island. After witnessing this 125-foot plunge along with thousands of other onlookers, a reporter from the Buffalo Republican claimed the ”jump of Patch is the greatest feat of the kind ever effected by man. He may now challenge the universe for a competitor.”

No other living entities—human or otherwise—stepped up to challenge Patch. He therefore sought only to better his own accomplishments and tour his talents around a larger area. Following the triumph at Niagara Falls, Patch turned his attention to the Genesee River, which flowed through the rapidly industrializing city of Rochester, New York. The river’s High Falls, which plunged from a height of 97 feet, seemed the perfect spot for the next great leap.

On October 29, 1829, ads touting Patch’s upcoming feat appeared in the Rochester Daily Advertiser and Telegraph. They promised “no mistake” could occur during the jump, requested that spectators bring a donation to help ease Patch’s travel costs, and noted that Patch’s newly acquired pet bear would also be making the leap. At the appointed plunge time—2 p.m. on Friday, November 6—between 6,000 and 8,000 people stood on the banks of the river awaiting the emergence of the much-heralded jumper and his animal companion.

The High Falls of the Genesee River in Rochester, where Sam Patch jumped twice in 1829. (Photo: Sean Liu/CC BY-SA 2.0)

Patch didn’t disappoint. According to the Rochester Public Library’s account, he first “took the bear by the collar and pushed it over the Falls into the turbulent water below.” Once the animal was confirmed to have survived the fall, Patch leapt after it. The whole thing went off without a hitch. Well, there was one hitch: Patch was disappointed by the final donation tally.

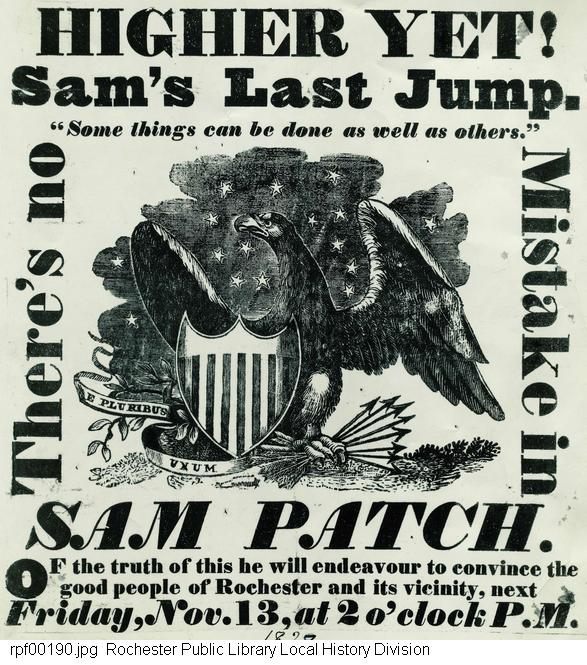

He decided to stage one more jump from the same spot in order to scrounge up some more cash. To entice repeat viewers, he arranged the construction of a platform that would rise 25 feet over the rock ledge, bringing the total jump height to 125 feet. Once again, ads appeared in the papers. This time they touted Patch’s “last jump.” Patch intended for the phrase to mean it was his final jump of the season. But the ads proved to be a lot more prophetic.

The advertisement for the second Genesee River jump. (Image: Public Domain)

At 2 p.m. on November 13—a Friday—Patch scaled the platform and stood above the thousands of spectators who had gathered to watch him leap. As had become his custom, he delivered a short, somewhat rambling speech in which he compared himself, favorably, to great historical figures. (“Napoleon was a great man and a great general,” he said. ”He conquered armies and he conquered nations, but he couldn’t jump the Genesee Falls.”) Witnesses later argued over whether he was drunk, or had just knocked back a quick shot of brandy to take the edge off the chilly November air.

Regardless, when Patch leapt, something wasn’t right. After descending the first third of the way “as handsomely as he ever did,” said the Evening Post, Patch “evidently began to droop, his arms were extended, and his legs separated; and in this condition he struck the water and sunk forever!”

The stunned crowd waited to see if Genesee River would produce Patch, or at least his body. There was no sign of him. It would be four months before his remains were discovered, seven miles downstream.

Public reaction to Patch’s final jump was mixed. While some lauded his dream-big-and-take-risks approach, the Anti-Masonic Enquirer chose to scold all involved, calling the incident “a daring and useless exposure of human life” that left the crowd “abashed and rebuked” after seeing the “frail mortal, standing, as it proved, on the brink of eternity!”

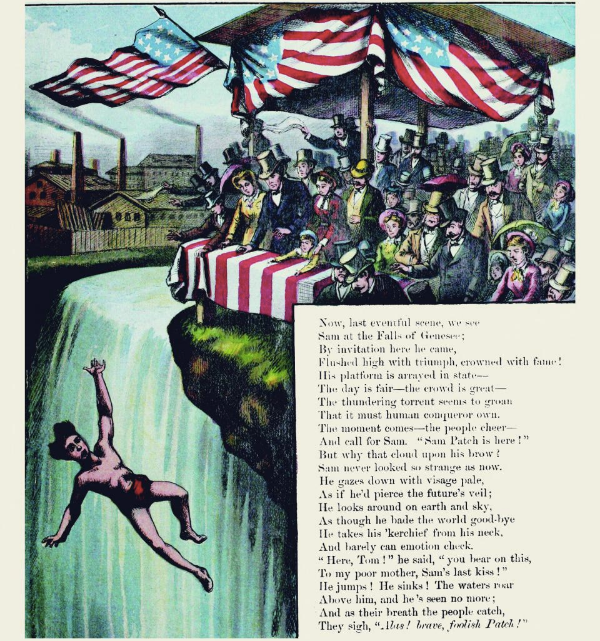

Once the initial shock and sadness had faded, a mythos began to build up around Patch. Over the next two decades, he kept popping up as a character. “Few persons in the United States of the 1830s and 40s could have avoided all the poems, ballads, rhymes, anecdotes, allusions, reminiscences, tall tales, and theatrical farces that celebrated the braggadocio jumper of history, fantasy, and hoax,” wrote Richard Dorson in “Sam Patch, Jumping Hero.”

Writers and other creatives of the 1830s, who were “swelling with Jacksonian nationalism” in response to the revolutionary president, turned Patch into a folk legend imbued with whatever profound and lamentable characteristics they saw fit. President Andrew Jackson himself even named his favorite horse Sam Patch in 1833.

The children’s book The Wonderful Leaps of Sam Patch, published in the 1870s, features an illustration of Patch plunging to his death. (Image: Public Domain)

Beyond these tributes was a more informal legacy: until well into the late 19th century, anyone who jumped from a great height into a body of water was referred to as a “new Sam Patch.” The New York Times cited several such Sam Patches over the decades, none of whom quite measured up to the real deal. This piece of reportage from 1853, entitled “Sam Patch Come Again,” sums it all up:

A couple of gentlemen were walking quietly across the wire bridge yesterday evening, and when about the middle, one of them stripped himself of all his clothes except his pantaloons, and jumped off into the river, a distance of about 150 feet. He swam to the shore and came up uninjured, except that he was very fatigued. The gentleman declined to give his name, but we understand that he is employed in the manufacturing works. This is certainly a capital way to cool off this warm weather, but most persons would prefer a shorter jump.

Whether Sam Patch was a drunken fool, an acrobatic hero, or some combination thereof, his leaping feats ushered in the daredevil philosophy: seek ever loftier heights, aim to astound, and get paid as much as possible for every reckless stunt.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook