This Siberian Subway System Has Just One, Non-Functional Station

Omsk was promised a Metro system in 1979. Forty years later, locals salute a subway that never saw the light of day.

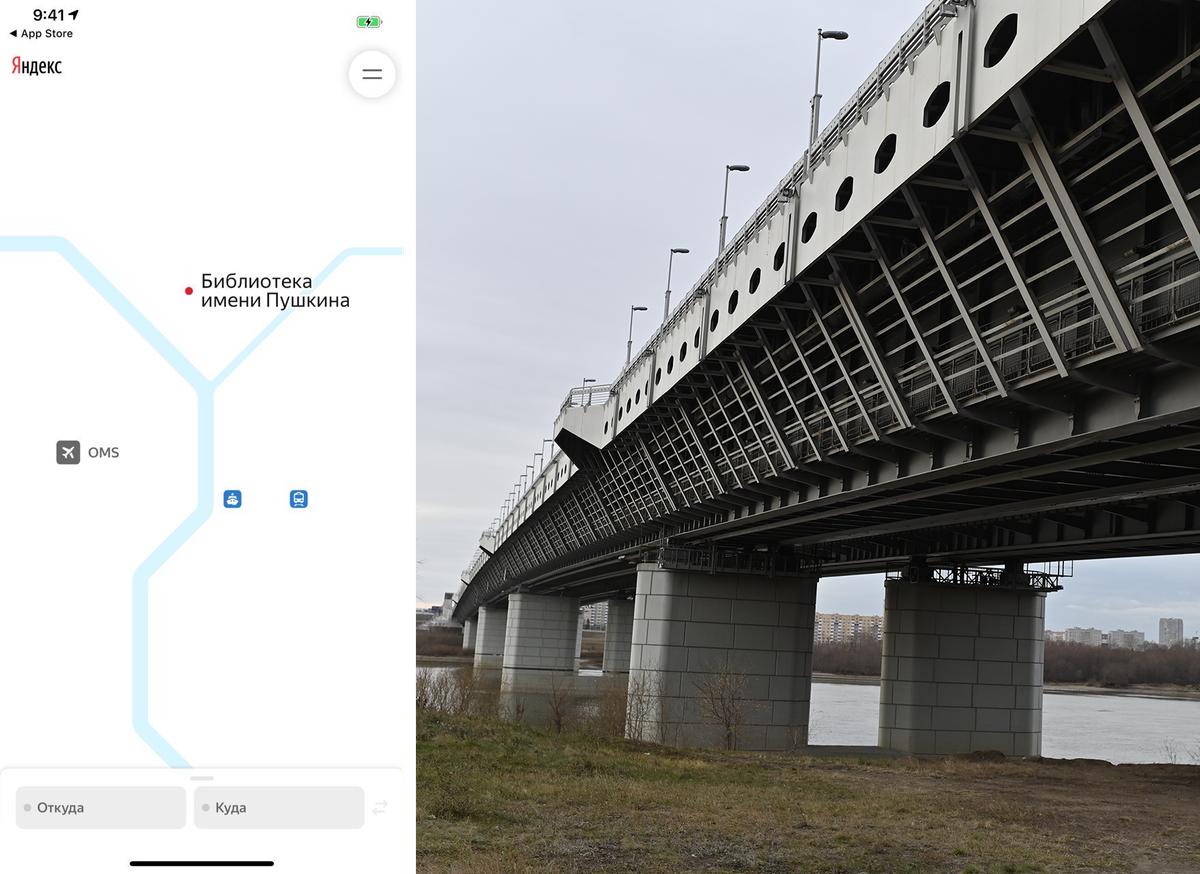

Earlier this year, a Russian transit app made a satirical update by adding a map of Omsk, a Siberian city around 1,400 miles from Moscow. The map showed an icon for the local airport, along with a train station on the Trans-Siberian Railway. Interestingly, it also showed a single red dot to mark a local Metro stop. There were no lines connecting it to nearby stations, and information about buying a ticket was nowhere to be found.

A subway map with only one station sounds like an absurdist gag. But the joke, pulled by the app Yandex.Metro, hit too close to home for residents of Omsk, who had been promised a functioning subway system since Soviet times. After decades of sporadic development, all that was accessible to pedestrians was a single underpass—complete with an M logo that adorns rapid-transit systems throughout Russia.

As a transportation project, the Omsk Metro was an ambitious dream that fell victim to a changing economic landscape and a dearth of federal funding. As a cultural phenomenon, it joined the ranks of many symbols for a struggling Siberian province. At the same time, for many citizens of Omsk, the subway that never was became a way to share appreciation for the city.

Compared to many other cities, Omsk was always well-connected to the rest of Russia, because it was a hub for both historical and modern routes of the Trans-Siberian Railway. Getting around the city itself, however, was hard—especially when it grew across the Irtysh river after the construction of an oil refinery. Walking anywhere became impractical, and the bridges of Omsk became traffic bottlenecks.

Around 1979, the population of Omsk hit a million, making the city eligible for a subway system funded by the Soviet Union. A few years later, the lead engineer on the Omsk Metro project, Vladimir Ryzhov, wrote in Metrostroy magazine that city was short on bridges and railway overpasses. Harsh frost, icy roads, and snowdrifts were also taking a toll. “Current means of public transportation in Omsk are not able to provide adequate service to commuters,” he concluded.

Ryzhov expected the construction to begin within five years. But he didn’t account for the cultural crisis within the communist regime, which led to drastic economic reforms and the eventual fall of the Soviet Union in 1991. In part because of the turmoil of that time, construction didn’t commence until 1992. The end of the U.S.S.R. created a new economic reality: Russian regions were expected to reduce their financial dependence on Moscow.

The Omsk region had the resources to sustain itself. Sibneft, a company that owned the refinery and oil plants, was one of Russia’s biggest petrochemical companies, and Omsk’s biggest taxpayer. But in 2006, the company moved to St. Petersburg after becoming an arm of a state-owned Gazprom, which deprived the region of $219 million in annual taxes.

In 2011, the now-infamous Pushkin Library station opened in central Omsk, to great fanfare. A bright red M was installed above the underpass, reflecting the high hopes that the city officials had for the project. Tunnels connected the station to the other side of the Irtysh River, though they were sealed to prevent trespassers. Leonid Polezhaev, the region’s governor who envisioned most of the construction, proclaimed that the subway would be put into operation within three years. This turned out to be wildly optimistic.

Yet for the city’s more creative citizens, that M was enough: Instead of waiting for the subway to be finished, they pretended it already existed, and started shaping its image. In 2016, Anton Oleynik, a photographer, copied the logo and drew the Pushkin Library archway on a napkin. Later, that sketch turned into a set of freshly minted coins, which could pass for real fare tokens. The tongue-in-cheek souvenir proved popular enough for the initial batch of 300 tokens to sell out. “The orders were coming from many different, remote cities of Russia. There were even buyers in Los Angeles and Las Vegas,” Oleynik says.

Graphic designers Violett and Dmitry Stolz decided to go even further. The same year, they created an original visual identity for the subway system, complete with logos and billboards. Violett Stolz, who has since moved to Prague, remembers a time when Omsk officials proposed a metrotram system, as a lower-cost alternative to a subway. “It would have been a great idea,” she says. “For me, the Omsk tram is the best public transit.”

Ultimately, even that alternative proved to be too expensive. In 2019, citing the lack of funding, Omsk officials announced that they were putting the development on hold. Forty years had passed since the idea first took hold. Some of the tunnels will be filled with sand and concrete, to preserve them for the future. “My whole life wouldn’t be enough to build everything. We were supposed to build four stations by 2016,” said Polezhaev after his retirement. “I didn’t get a chance, and I’m sorry.”

That didn’t stop people from looking for new meanings for the subway. “It’s hard to live in a city with a corpse lying in the middle of it,” says Ivan Pritulyak, a former radio host from Omsk. “But Siberia is a place where everyone has to help each other and make the most of any resources.” Pritulyak envisioned a two-year series of art events on a Pushkin Library station, and the idea has built momentum.

The first exhibition, organized by the Vrubel Museum of Fine Arts, is scheduled for December. But Pritulyak doesn’t think the station should be seen as just an underground museum hall. “Let’s look at it as a multipurpose space,” he says. “It can host visual arts, but it can also be used for concerts, plays, media arts.”

Recently, research conducted by the Russian Ministry of Construction and Strelka KB awarded Omsk 104 points out of 360 in the index of urban environment. While the researchers didn’t compile a comparison chart, the score puts Omsk in the bottom 10 of the list, making it the least pleasant Russian metropolis to live in.

Transportation infrastructure continues to be one of Omsk’s weakest points. Irina Ogarkova, a merchandiser, has to take a ride from Neftyanikov district, in the northwest part of the city, to Moskovka district, in the southeast. Her 13-mile ride goes through the busy city center, and marshrutkas—minivans run by small businesses—keep jamming the traffic.

As nice as it would be to have an underground alternative, Ogarkova admits the city might never be ready for it. “It would be nice to spend 15 minutes to move from one point to the other—not two hours,” said Ogarkova. “But given the financial state, I think it’s impossible. The subway would be an expensive toy for a city facing a budget gap. If it was built, I think only a small number of citizens could afford to take a ride daily.”

For many Russians in the rest of the country, Omsk can seem like more of a meme than a real city. It has earned a sarcastic slogan: “Don’t try to leave Omsk.” At one point, the motto was even blamed by the acting governor of the region, Alexander Burkov, for scaring away investors. In the 2000s, Russian web users suggested a new name for “Winged Doom,” an eerie painting of a bird by Heiko Müller. They called it “Omsk Bird.”

Even while embracing the failure of the subway, citizens of Omsk want the symbol of the city to carry a more positive meaning. “I associate the city with self-development,” adds Violett Stolz, the graphic designer. “Omsk is shaped not by its officials, whom I can say nothing about, but by its local projects, young people, and places and businesses they build.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook