For Decades, New York’s Chinatown Duped ‘Slum Tourists’ With Faked Danger and Depravity

Opium dens, gunfights, and poverty theater.

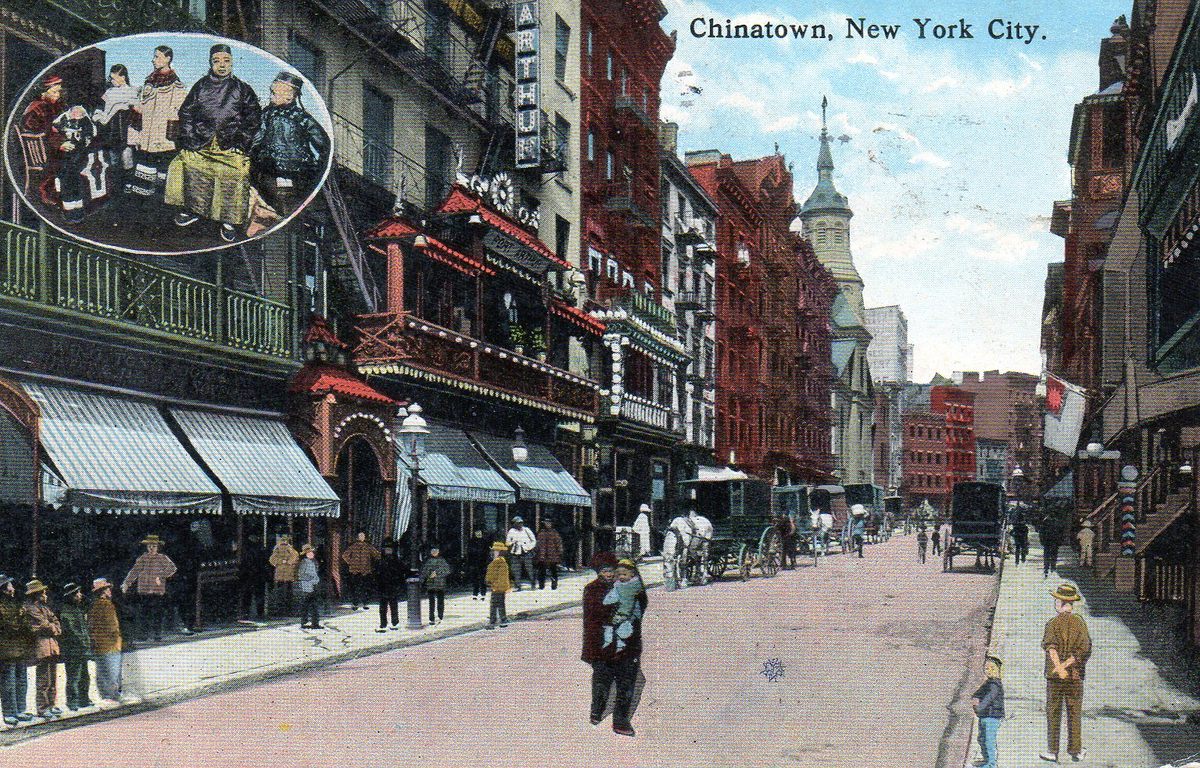

The slums of early-20th-century New York were, to a certain white, upper-class clientele, exotic, foreign, even exhilarating. In Chinatown, gunfire might spontaneously break out between rival gangs. The visitors might sit down to dine on “authentic” chop suey, among people speaking an unfamiliar tongue. They might see white women lounging in seedy opium dens with Chinese men. They might leave convinced that they had seen “one of the world’s wickedest spots.” But they had no way to know that much of what they had seen was an elaborate stage show, put on to fool gullible white tourists, engaged in the act known as “slumming.”

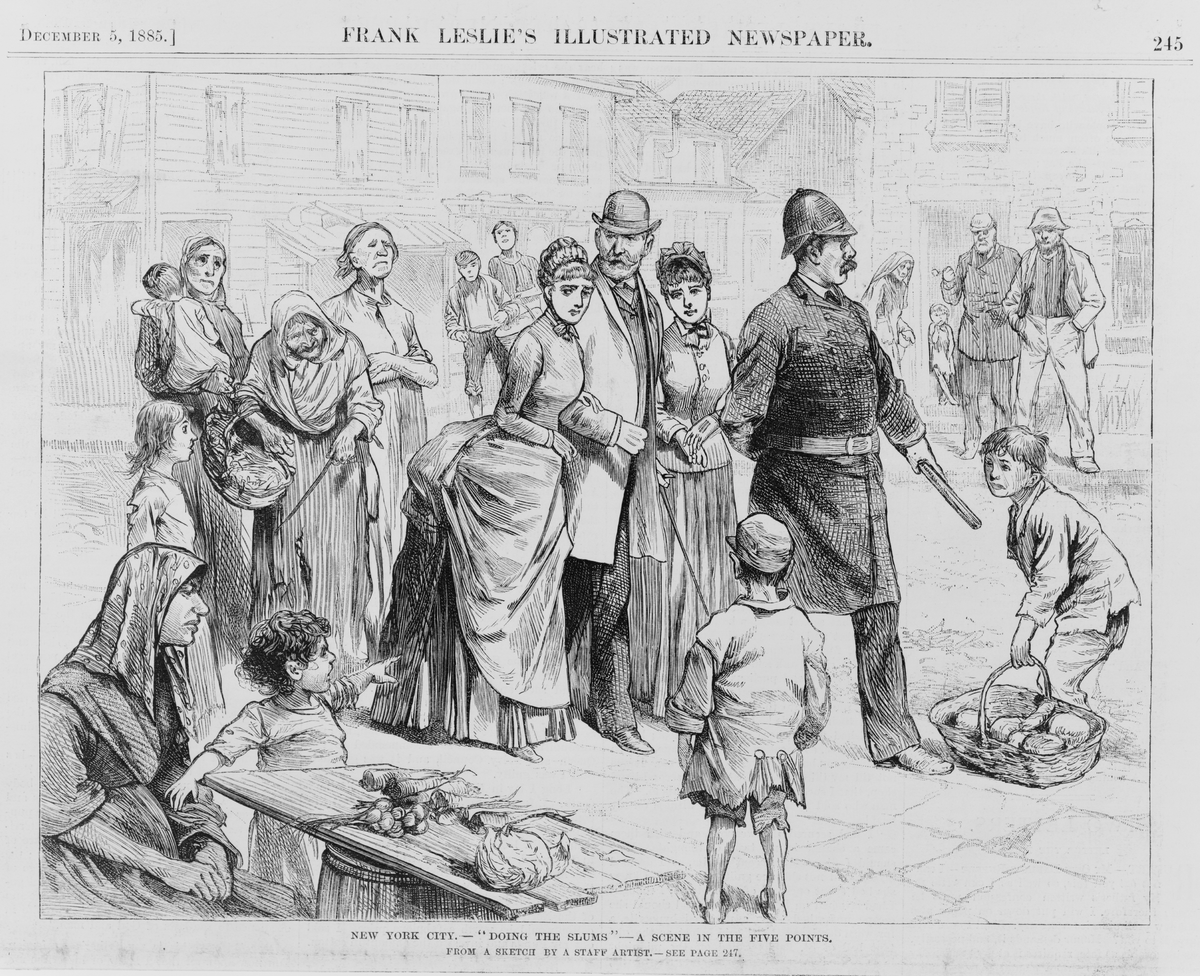

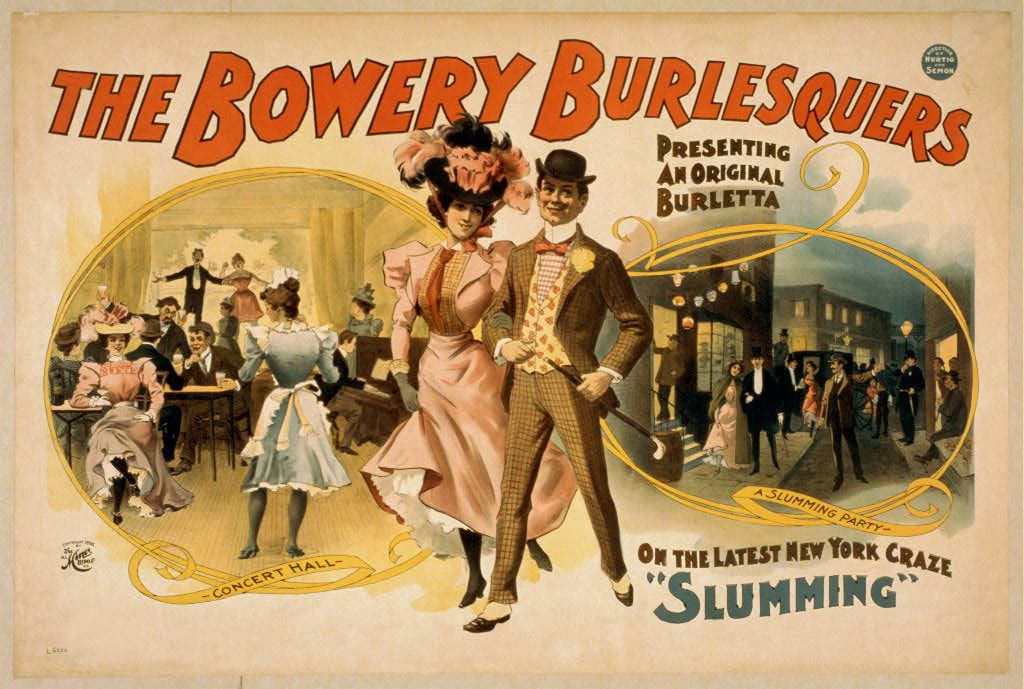

Slumming is a tourist practice that made its way to the United States from the United Kingdom sometime in the 1880s. It initially came from the reform impulse, but quickly consumer culture kicked in, and it became a means for more affluent white Americans and Brits to gawk at those with radically different ways of life. In September 1884, The New York Times ran the headline “A Fashionable London Mania Reaches New York,” and described how slumming was certain to become the amusement of choice for “our belles” that winter.

In one form or another, it persisted as a form of tourism until the beginning of the World War II. At that time, the rise of suburbs and television, among other factors, seemed to put it to rest. But beginning in the 1980s, slum tourism has come back with a vengeance and a more international flavor, with tours that see affluent white visitors passing through what are considered slums in countries such as India, South Africa, and Brazil. It’s sparked controversy and moral outrage. Some see it as a racist exercise that taps into a universal fascination with inequality and the less fortunate. Others claim it pumps money into critically poor neighborhoods, as well as the pockets of tour operators. Indeed, in some cases, a significant proportion of slum tourism profit has been pumped back into the communities. But it still represents, to many, poverty as entertainment.

It was different when it began in 19th-century London, where wealthy people traveled through poorer or ethnic neighborhoods in the guise of a “reform enterprise.” At its best, the practice might result in lobbying for improved lighting or ventilation, or even the whitewashing of walls of low-income housing. In more oblivious moments, so-called “flower charities” would distribute “floral gifts” to the downtrodden people they saw. The Times gushed, “What a pleasure it must be to a sufferer imprisoned in one of these tenements to receive a flower, with its color and its green leaves and stems!”

The pretense of high-minded purpose was swiftly abandoned in its American incarnation. Sometimes guided groups swept through Harlem or the Lower East Side, and flung open the front doors of unsuspecting residents. Wealthy observers saw what was to them almost incomprehensible poverty. At that time, New York was the most densely populated city in the world: Parts of the Lower East Side had up to 800 residents per acre. “Ladies and gentlemen” donned common clothes and went out, the Times reported, “in the highways and the byways to see people of whom they had heard, but of whom they were as ignorant as if they were inhabitants of a strange country.”

Much of what they saw was indeed representative of the ordinary lives of the people who lived in these areas, but, in slumming, some saw an opportunity. A homegrown industry quickly arose to give the gawkers something to gawk at, and to keep them spending money. Slummers went on these expeditions to see scandal or, at the very least, impropriety, often in ways that would reinforce the sexual and racial stereotypes they already held. They wanted to see the unclean, the “primitive,” the highly sexed. “The women and men who found themselves on the receiving end of this practice did not always take kindly to the primitivism that slumming reified,” writes Chad Heap in Slumming: Sexual and Racial Encounters in American Nightlife, 1885–1940. Understandably, the residents were similarly displeased by the “seemingly constant traffic of outsiders that surged through neighborhood streets.” But where there was demand, there was money to be made.

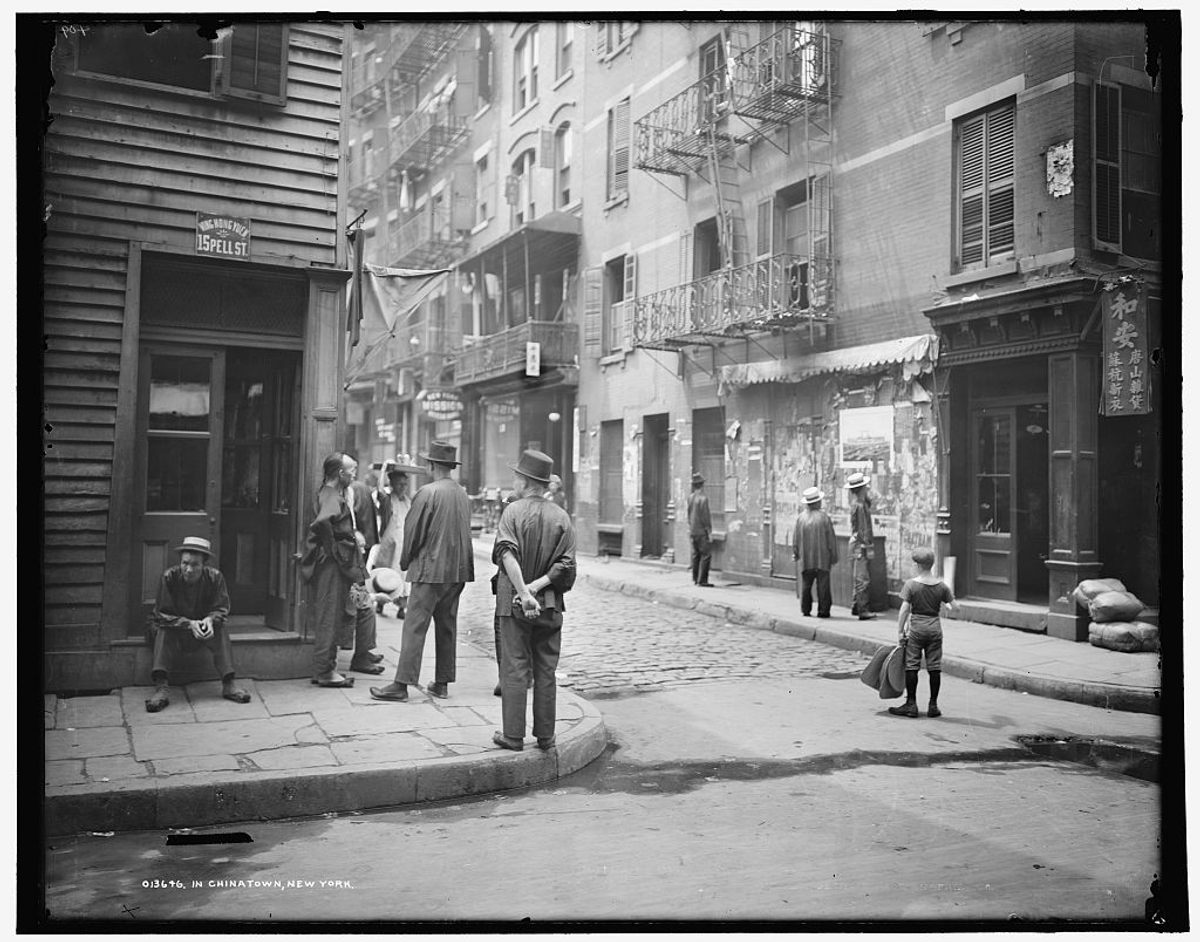

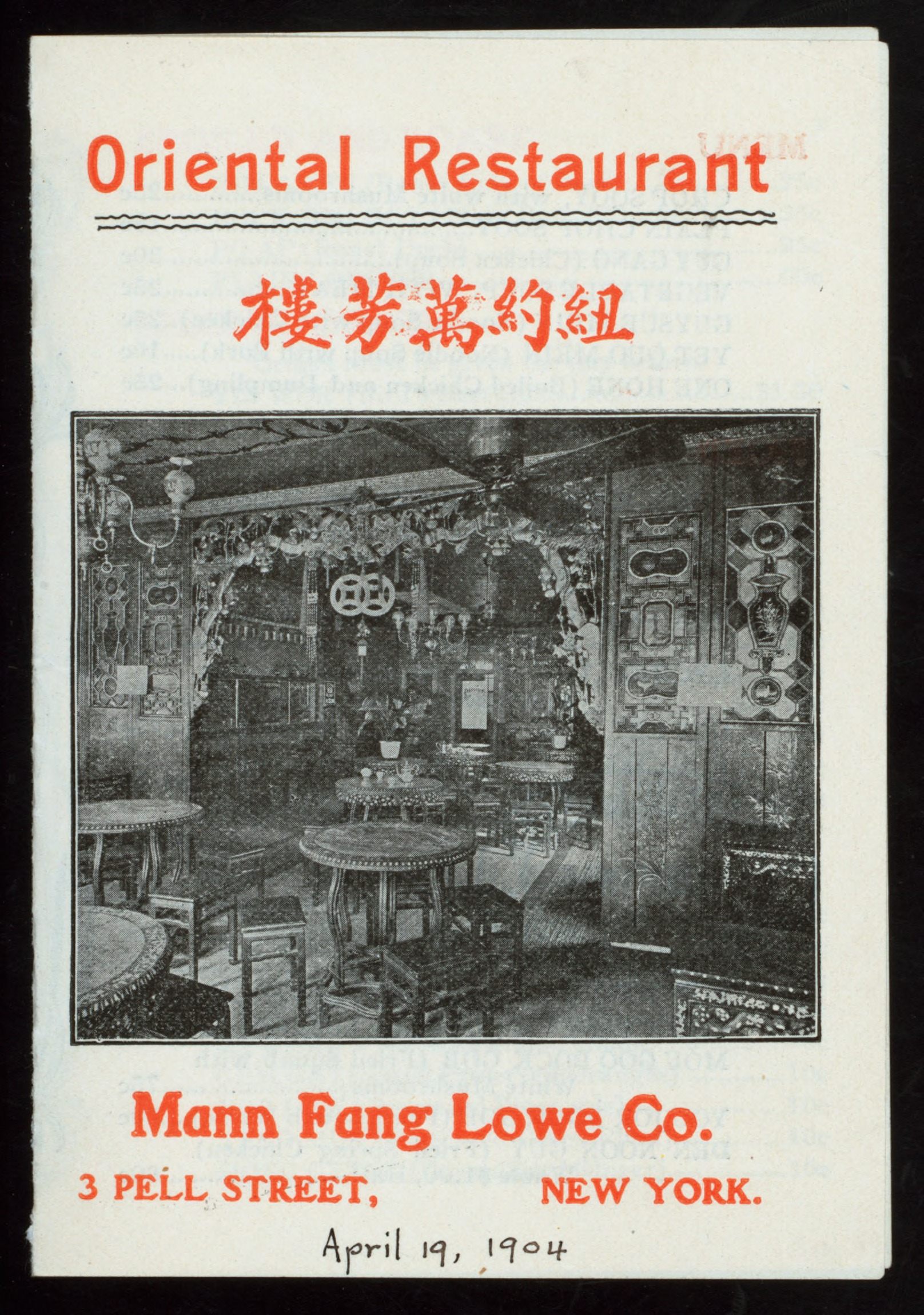

In some cases, this involved the opening of “authentic” eating and drinking establishments, which stayed open far later than ordinary neighborhood demand would require, to appeal to wealthy pleasure-seekers. Many examples in Chinatown, Heap says, were not necessarily owned by Chinese immigrants or Chinese Americans. “They tended to be run and operated by other immigrant groups, like Italian or Jewish immigrants, often.” Chop suey joints, for instance, opened throughout Chinatown to serve a bastardized version of a Cantonese noodle dish as late as 3 a.m. In 1903, The New York Times described it as a “cheap and substantial dish” (waiters didn’t even require tips!), served to the “midnight supper crowd.” Many of these restaurants served both “exotic” food and typical American fare for those with less adventurous tastes. In time, chop suey grew so popular that it spread across the city and, eventually, the country.

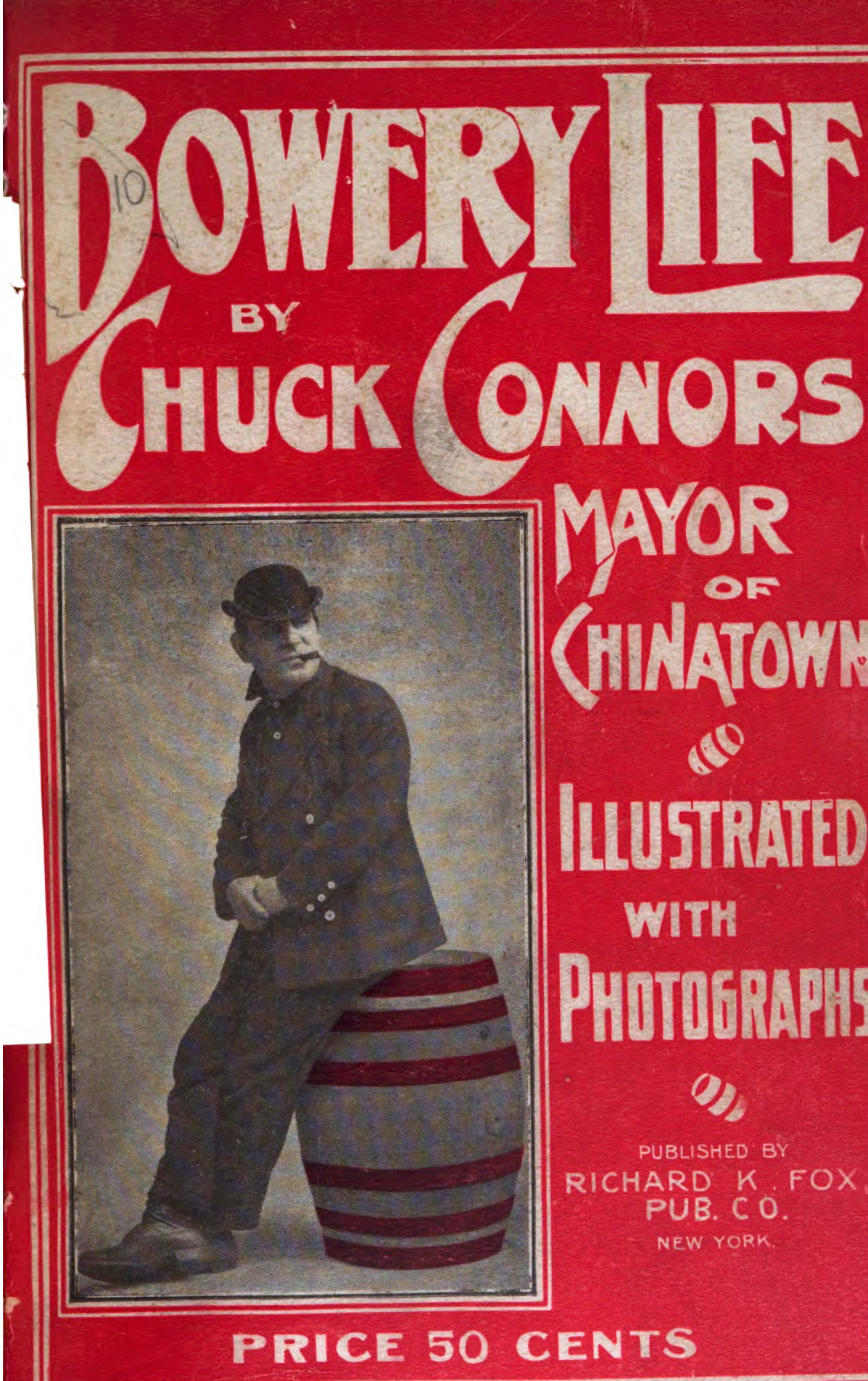

Affluent slummers often employed guides or joined organized groups. Industrious young men—independent “slumming guides”—capitalized on the crowds by introducing them to brothels or saloons that were accustomed to hosting slummers, or had sprung up specifically to do so. Usually white and working-class, these “lobbygows,” as they came to be known in Chinatown’s pidgin English, marketed themselves as critical cultural conduits to the exotic, unfamiliar Chinese. They even advertised in local papers and came to be seen as legitimate businesses. In Chicago, for instance, in 1905 a local resident sought police approval to establish “a guide system to escort slumming parties and show strangers the sights.”

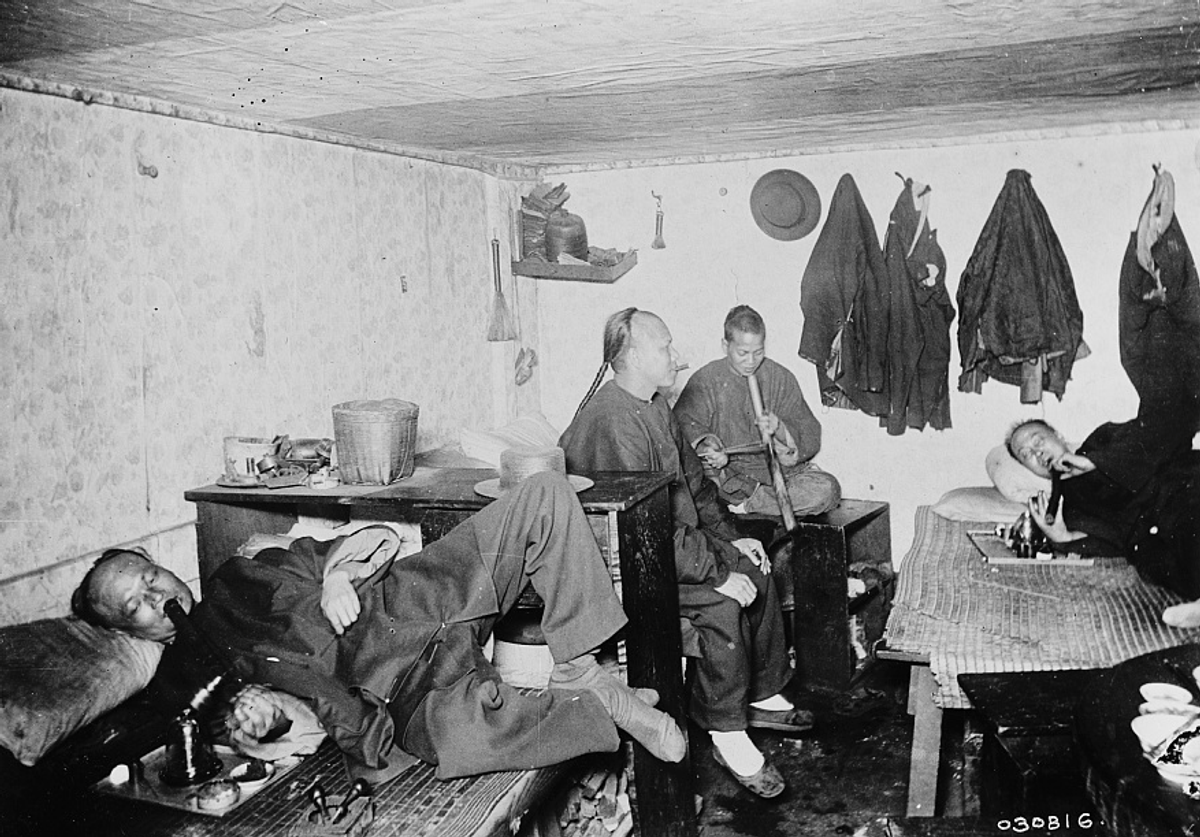

One of the most famous was Chuck Connors, who declared himself Mayor of Chinatown and took celebrities such as actress Ellen Terry and businessman and tea magnate Sir Thomas Lipton on his trips. Connors was made famous by his 1904 book Bowery Life, which described his curious dress—“a short coat with white pearl buttons, a white tie and a very small hat”—and was mostly written in an odd attempt at his own vernacular: “It nearly took me bre’th away t’inkin’ uv it, an’ I ain’t got over it yet.” Connors took his tours to a Chinese restaurant, the popular Chinese theater, the Mott Street “joss house” or temple, and what slummers believed to be an opium den, where wide-eyed Chinese people lolled around, seemingly stoned out of their minds.

Visitors could hardly believe their eyes—and they would have been right not to. These opium dens were entirely staged, with Chinese actors employed to give viewers something to look at. With or without a guide, slummers would likely not be allowed into “real” opium dens simply to gawk. “I don’t think an opium den would have welcomed, or allowed access to, slummers to come through if they weren’t there to smoke themselves,” Heap says. Some whites did indulge, and sometimes developed serious addictions—but not in the ersatz recreations Connors showed his clientele.

In these places, everyone was a professional actor. In at least one case, the Chinese actor playing one addict was secretly married to his white, drooping female companion. They repeated the hammy performance many times in an evening. Slummers left feeling as though they had seen something decadent, degenerate, depraved, and possibly even dangerous.

Meanwhile, on the street outside, a fight might break out. The Tong Wars, Chinese gang infighting, were covered extensively by the local tabloids. As gunfire sounded on Pell or Mott Street, slummers got a taste of danger. They likely would not have imagined that this was a show, timed for their arrival and designed to shock. Visitors who didn’t see something that made them duck or clutch at their pearls were often disappointed. A former New York police officer, Cornelius Willemse, remembered, “They’ve built up such fantastic ideas [of Chinatown] that if they don’t see a few Chinamen disappearing down traps in the pavement pursued by somebody with a hatchet or a long curved knife, they haven’t had any fun and they go home disappointed.”

A 1908 film satirizing these practices, The Deceived Slumming Party, features white actors in racist yellowface portraying Chinatown locals. A touring car of slummers sees a series of shocking sights: a police raid, the apparent suicide of a white female opium addict, roughhousing that descends into murder. Just in time they are whisked back to safety—and their tour guide runs back to pay the actors. In San Francisco, trips of this sort were eventually banned. The Times report on the ban finished: “The opium smokers, gamblers, blind paupers, singing children, and other curiosities were all hired.”

There was little actual danger. After an undercover study in the late 1910s, an investigator reported that the “sham and fake in the Village for the benefit of the uptown slummer crowd” was “about as dangerous as a Sunday school sideshow.” It’s hard to know whether people knew they were being fooled, because so few first-hand accounts of the practice have survived, Heap says. “I think they’d go thinking they were seeing something authentic. And I think sometimes they did see things that were really authentic, and in cases they’d see things that were really staged.”

Out-of-towners were particularly susceptible to being duped, while locals might be more astute. The poet James Clarence Harvey, in 1905, wrote: “Slumming usually means paying a price to see others do things you wouldn’t do yourself for the world, and which perhaps they wouldn’t do except for the price you pay.” People wanted a spectacle, and they got it. Some local residents were frustrated by these attempts to play to the rubberneck crowds. In 1936, Loeng Gor Yun wrote, in Chinatown Inside Out, “Smokers and non-smokers alike are outraged by this false local color daubed on Chinatown by bus companies, but they are powerless, beyond a sneer or a smirk, against the lies they hear being fobbed off on groups of gullible tourists.”

It was in one sense a profoundly inauthentic view of life in poor or ethnic neighborhoods, but Heap is more circumspect about what “authenticity” means here. The behavior might have been staged, but the slumming venues were authentic, inasmuch as they were doing what they were set up to do—immersive theater. Chop suey wasn’t “real” Chinese food, but itself became a genuine, distinctive dish. “Some of these venues are creating a new kind of authenticity,” he says. “It’s not like people are transported away to the old country and are getting a glimpse of ‘what really happened.’” Indeed, the boring routine of everyday life, though different uptown and downtown, was what slummers were trying to escape in the first place.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook