The Hidden History of Bathing in Soup Broth

Doctors and folk practitioners alike swore by its healing properties.

The old German font was hard to decipher, so I sent the newspaper article to a professor who spends half his life immersed in the gothic script. “This is from 1848,” I wrote. “Does it really say what I think it says?”

I was researching the 19th-century European vogue for eating horsemeat, a movement spread across the continent by “hippophagic societies” whose members believed that broken-down workhorses should be fed to the growing proletariat. I was used to accounts of scientists and do-gooders tucking into “Pegasus filet” and fine wines, but this was something else. “It is what you think it is,” the professor wrote back. “They’re bathing children in horse broth.”

According to “the informed opinion of an experienced physician,” the brief news item from Berlin recounted, horse bouillon bathing had proved itself in medical applications, especially in pediatrics. It wouldn’t be just the wealthy who could indulge, the article went on, implying that baths of broth would be affordable for the lower classes, too.

In 1848, German enthusiasm for horsemeat was still new, but the dark red flesh already had a reputation as a health food. The chemist Justus von Liebig claimed that horse contained more creatine for muscle building than beef or mutton, and the new horse-butchering establishments were well-regulated and clean. But even if horsemeat was cheap, why bathe in a tub filled with bouillon?

It turns out that Europeans have a long history of steeping themselves in meat soup, although I found that references were scattered and scant. Vats of horse broth played a role in pagan Indo-European rites across Europe and Asia in which the equine was sacrificed, dismembered, and boiled. This may have inspired the first mention I found of a broth bath, dating from the late 12th century. Gerald of Wales, clerk and chaplain to King Henry II of England, was dispatched to Ireland to report on the locals. Gerald portrayed them as godless brutes in an account now viewed as unreliable, anti-Irish propaganda. He described the new king of an Ulster tribe bathing in broth made from a sacrificed white mare with which he had just had intercourse. The king sipped on the broth as he soaked. Several modern scholars have pointed out the similarities between this (probably) imaginary rite and the ancient Indian Vedic horse sacrifice known as the Ashvamedha. Although in that case, the queen symbolically sleeps with the horse, and no one bathes in the broth.

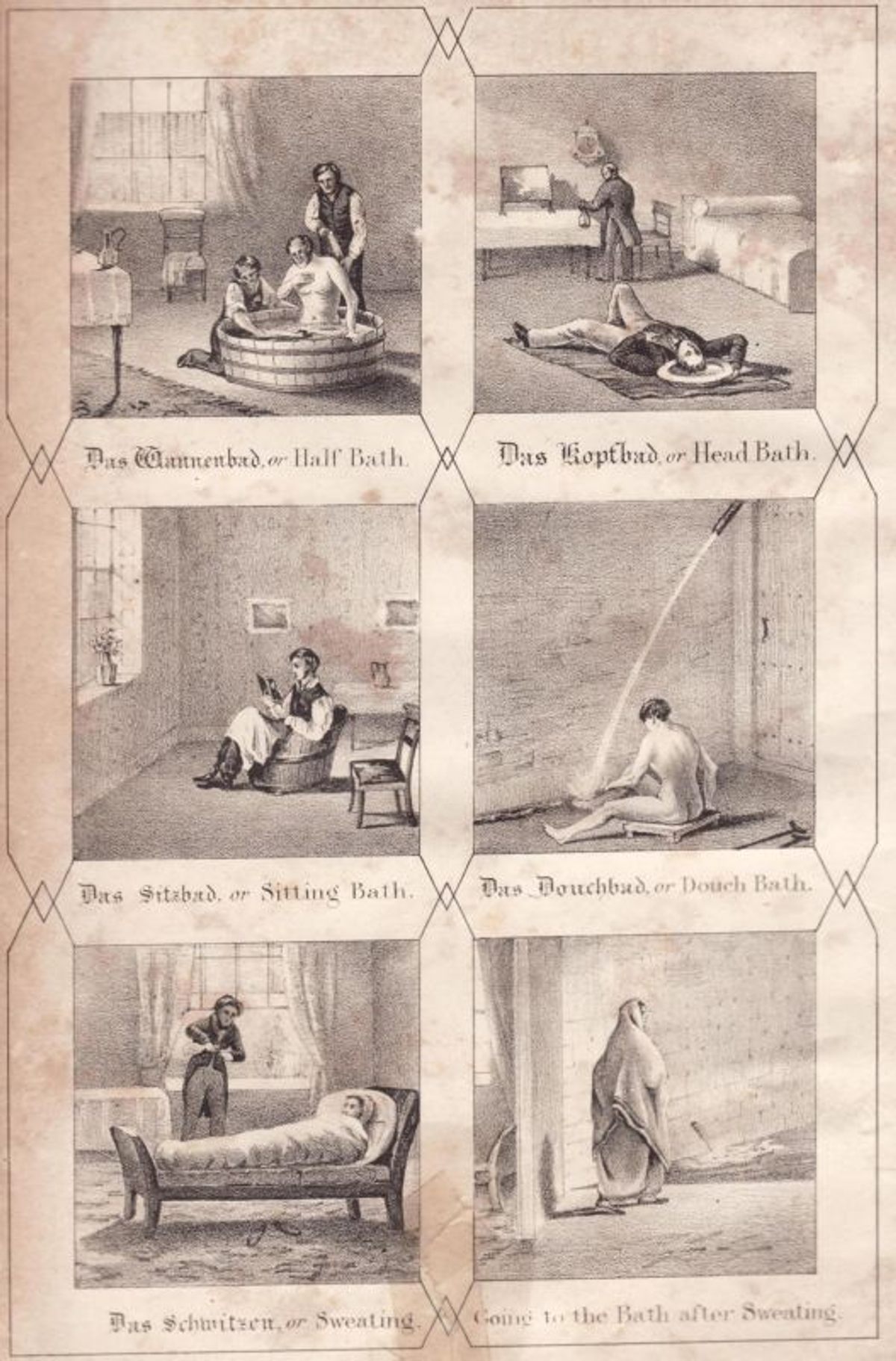

Less luridly, broth bathing appears to share a tandem history with “hydrotherapy,” the therapeutic immersion of the body in warm mineral water. Classical writers such as Pliny the Elder believed that different natural springs had distinct mineral properties that cured diverse ailments. While therapeutic bathing fell into disrepute after Roman baths became associated with sexual licence, the rediscovery of classical texts in the Renaissance led to renewed interest. The Swiss doctor Theophrastus von Hohenheim (or “Paracelsus”) prescribed bathing in spring water to remove mercury from the body. Physicians believed that skin was permeable, so if mercury could seep out, then surely the hearty properties of spring water or bouillon could seep in.

In 1782, the wonderfully named Dr. Rhodomonte Dominiceti opened a bath house in Panton Square near Haymarket in London, where customers could experience not only “artificial baths” in his own recipe mineral water, but also wallow in “veal or other broths” for the princely sum of three to five guineas. Just four years later, the Scottish anatomist William Cruickshank was claiming that Paracelsus himself had kept men alive for several days by sitting them in broth or milk baths. (Cruickshank thought they absorbed the nutrients via their rectums. They did not.)

While broth bathing does not seem to have been on the menu at the grand spa resorts of the 19th century, it remained a folk and medical custom across a wide geographic region. In 1856, a traveling Englishwoman staying with an aristocrat in the Italian town of Macerata was informed by her local maid that babies were often soaked in a brodo lugo: a light broth of lean veal with all the fat skimmed off. She recommended it for the English lady’s complexion, because “it softens and yet nourishes the skin.” A German medical text from the same year records typhus patients in Russia taking bouillon baths as part of their recuperation. A later German medical handbook, meanwhile, contains recipes for a sheep-foot broth bath and dissolved Thierleim, a brownish, gluey jelly made from boiled hoofs, bone, skin, and tendons. The handbook does not specify which ailments they were meant to treat.

Broth baths came to America, too. An early settler in 1850s Texas named Mary Ann Maverick recorded in her diary that when her newborn daughter didn’t fatten up, “Mrs. Salsmon, an experienced German nurse” recommended boiling beef bones for four hours before cooling them to “one hundred” and settling the baby in the broth. The baby should then be removed and wrapped in a blanket without being dried, and set to sleep. Maverick did so, and, within days, the little girl was putting on weight.

As the medical establishment increasingly relied on better science, however, doctors turned skeptical. In Dr. Hermann Eichhorst’s 1887 Handbook of Special Pathology and Therapy for Practical Doctors and Students, meat-broth baths are described as “without benefit.”

Not that everyone listened. The notion of a nourishing bath is still irresistible. Magical thinkers of the 21st century bathe in milk, caviar, olive oil, wine, and even coffee at wellness spas, and one Japanese firm makes miso-soup bath sachets for the ultimate comfort experience. For those who enjoy the unmistakable cognitive dissonance of realizing that any bath, whether you’re tipping in Epsom salts to season or not, is a sort of human soup, a hotel in the Philippines offers the chance to bathe among floating coconut leaves with a fire going under the pot, like old comic-book images of clueless cannibal victims.

Definitively calculating how popular or widespread broth bathing was throughout history would be a major research project that has, alas, not yet been conducted. But I can say that it was an established-enough practice to appear in medical textbooks and spa menus. There may have also been long folk traditions that the written record barely reveals.

I did stumble on one last, modern story. A linguist friend told me that on a research trip in rural Armenia, she met an Assyrian woman who followed local practice and bathed her baby boy in beef broth “to strengthen his bones.” The baby thrived.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook