The Anti-Monopoly Board Game That Promoted a ‘Soviet America’

In 1934, American Communists translated a Stalinist book about revolution into a children’s game. Curiously, it didn’t catch on.

The 1930s were the golden age of board games. With millions of Americans out of pocket due to the Great Depression, board games were one of the cheapest forms of entertainment. One of the most popular games of the decade was Monopoly—no doubt precisely because it allowed players to imagine themselves getting rich and powerful.

Like Monopoly, but the Exact Opposite

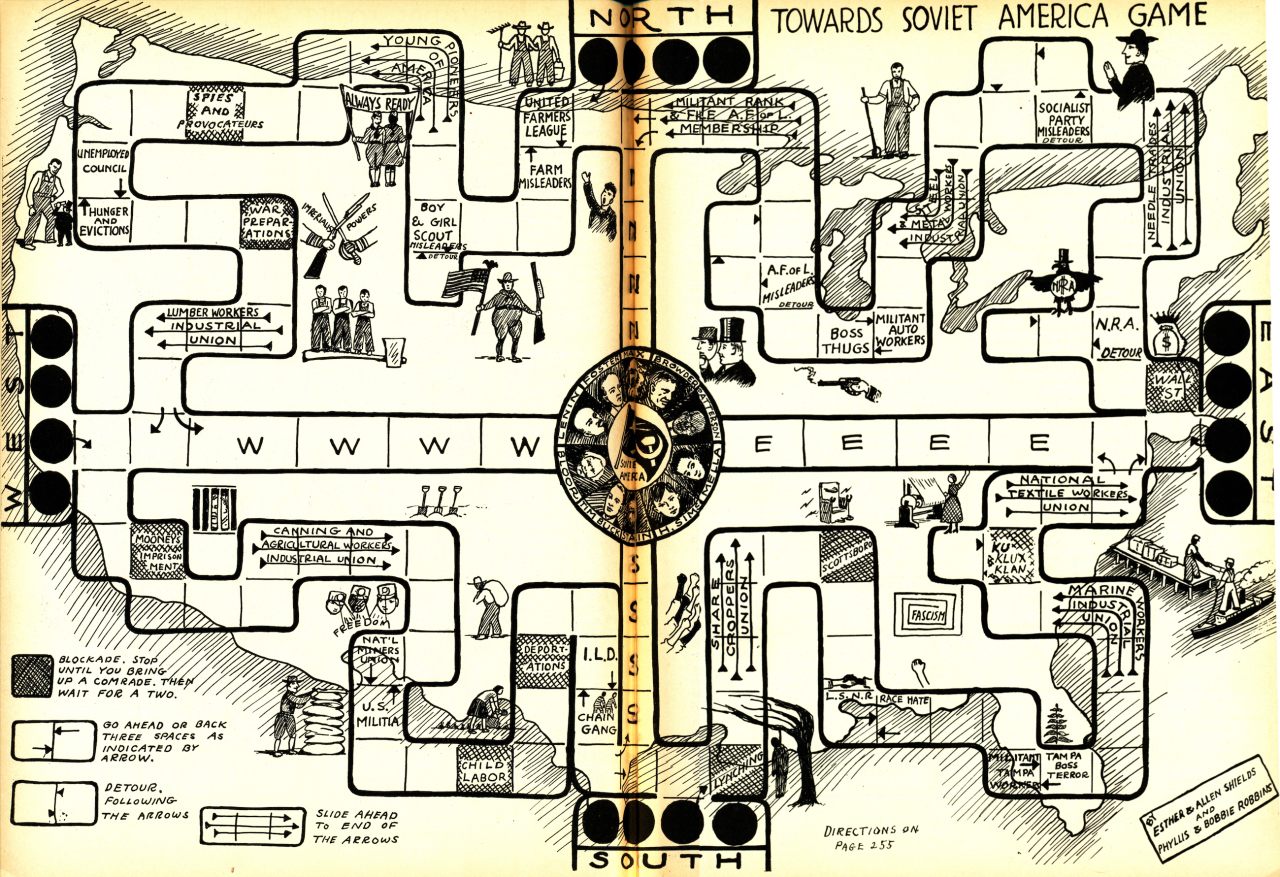

One board game from the early 1930s was Monopoly’s diametrical opposite. Instead of celebrating capitalism, it aimed to destroy it. The players’ goal is to get rid of the rich and powerful, end oppression, and seize the means of production. Ultimately, their actions will turn the USA into the USSA—the United Soviet States of America.

The game was called Toward Soviet America. As you may have guessed by its absence from your family room, it never caught on. When we take a closer look at the board, the book that inspired it, and the author of that book, we get a glimpse of a now obscure chapter in America’s sociopolitical history—one in which the Communist Party of the USA (CPUSA for short) saw the proletarian revolution in America as imminent and itself as the inevitable vanguard of the toiling masses.

Not coincidentally, the 1930s were also the golden age of American communism. The United States wasn’t yet in a Cold War with the Soviet Union, ground zero of the world revolution. And the misery of the Depression was working in the CPUSA’s favor. In 1932, William Zebulon Foster, Secretary-General of the CPUSA, got more than 100,000 votes in the presidential election, more than any communist candidate before or since. Still, that was just 0.3 percent of the total.

“America’s Lenin” Gets a State Funeral

Foster’s electoral irrelevance—in his two previous presidential runs, he garnered just 0.1 percent—and the political hostility he faced at home stood in stark contrast to the respect and consideration he received in the USSR. “America’s Lenin” was a loyal servant of Moscow and a welcome guest even after his retirement in 1957.

It was on one such visit to the USSR in 1961 that Foster died, aged 80. The “Chairman Emeritus” received a state funeral—surely the only U.S. presidential candidate ever to be thus honored. The funeral took place in Moscow’s Red Square, and the honor guard was headed by Nikita Khrushchev himself.

Foster’s most lasting legacy is Toward Soviet America. Published in 1932, the book “explains to the oppressed and exploited masses of workers and poor farmers how, under the leadership of the Communist party, they can best protect themselves now, and in due season cut their way out of the capitalist jungle to Socialism.”

In its latter chapters, the book describes life as it could be in a future Soviet America:

The establishment of an American Soviet government will mark the birth of real democracy in the United States. For the first time the toilers will be free, with industry and the government in their own hands. Now they are enslaved: the industries and the government are the property of the ruling class.

Reverse Propaganda

Curiously, after World War II, the book’s propaganda value was reversed. Toward Soviet America was disavowed as incorrect and outdated by both the CPUSA and Foster personally—and reprinted by their opponents, with plenty of notes, as a clear indication of what the Communists’ real goals were for the country.

In its heyday, however, the CPUSA judged Toward Soviet America important enough to turn it into a board game. The board was printed in the March 1934 issue of New Pioneer, a communist youth magazine. In an uncharacteristic capitulation to free market dynamics, the CPUSA must have realized that a popular board game would be a better vehicle for the “Sovietization” of young American minds than a 340-page Stalinist diatribe with passages like this one:

In no country is culture so debased by capitalism as in the United States. Essentially a gigantic effort to perpetuate the robbery of the workers, it is sterile, hypocritical, colorless, lifeless. America’s capitalistic writers are engaged in trying to convince the working class what a glorious thing it is to be a wage slave; her artists and poets are busy glorifying Heinz’s pickles and the advertising pages of The Saturday Evening Post; her dramatists and musicians are cooking up patriotic slush and idiotic sex stories to divert the masses from their troubles and the hopeless boredom of capitalist life; her scientists are trying to prove the unity of science and religion, etc., etc.

Soviet America, the Beautiful

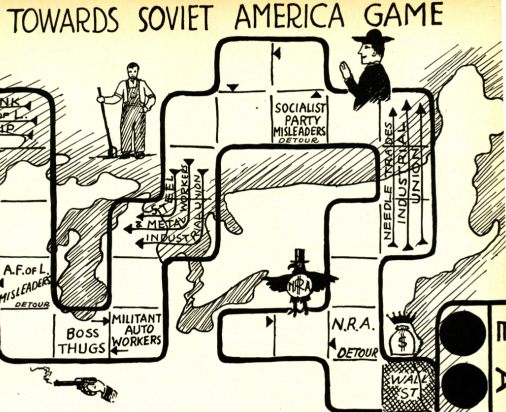

So, how do you play Toward Soviet America? Up to four players start with four “men,” each in one of the four cardinal directions. They must make a circuit of the United States, visiting its many social injustices, before entering the “home stretch toward Soviet America.”

Players advance using a button toss, spinning a cardboard dial, or drawing numbered cards. For some reason, dice were not an option for the young pioneers. Perhaps they were deemed too frivolous.

Along the way, you can land on squares that are conducive to the inevitable proletarian revolution (United Farmers League or Militant Auto Workers—advance three spaces), or to bourgeois or revisionist detractions (Farm Misleaders or Boss Thugs—go back three spaces). If you’re unlucky, you’ll land on a “blockade” (Child Labor, Deportations, Ku Klux Klan), where you’ll have to wait for a comrade to arrive to set you free.

When you’ve gone around once, head for the center, where communist utopia awaits. The egalitarian Walhalla is populated by such communist luminaries as Vladimir Lenin, Karl Marx, and Joseph Stalin (because of the centerfold, the latter two names read as Max and Stain), as well as Foster.

An American Communist Pantheon

Other names on the roundel represent further members of the American Communist pantheon, including Ella Reeve Bloor (“Mother Bloor,” a feminist activist), Earl Browder (CPUSA leader in the 1930s and early 1940s), William L. Patterson (an African-American leader), Julio A. Mella (a founder of the Cuban Communist party), and Tim Buck (General-Secretary of the Communist Party of Canada).

These communist heroes are now all but forgotten. If, through some freak of history, William Z. Foster had won the 1932 presidential election and Soviet America had become a reality, their names and faces would be as familiar to us now as those of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and Abraham Lincoln. And Foster would have gotten a state funeral in Washington instead of Moscow.

This article originally appeared on Big Think, home of the brightest minds and biggest ideas of all time. Sign up for Big Think’s newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook