The Artful Propaganda of Soviet Children’s Literature

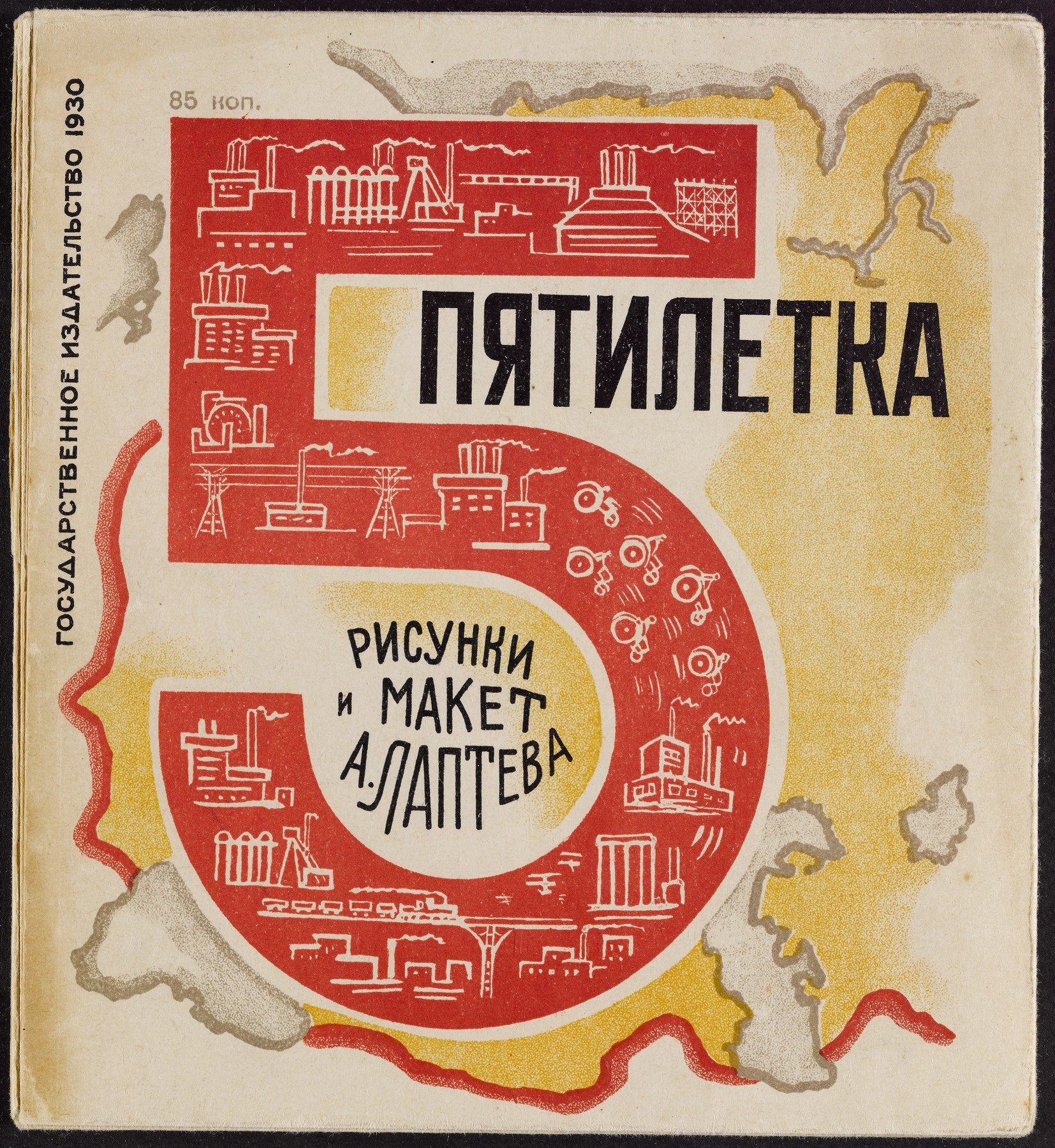

In 1920s Russia, children read about sugar beets, hydroelectric plants, and five-year plans.

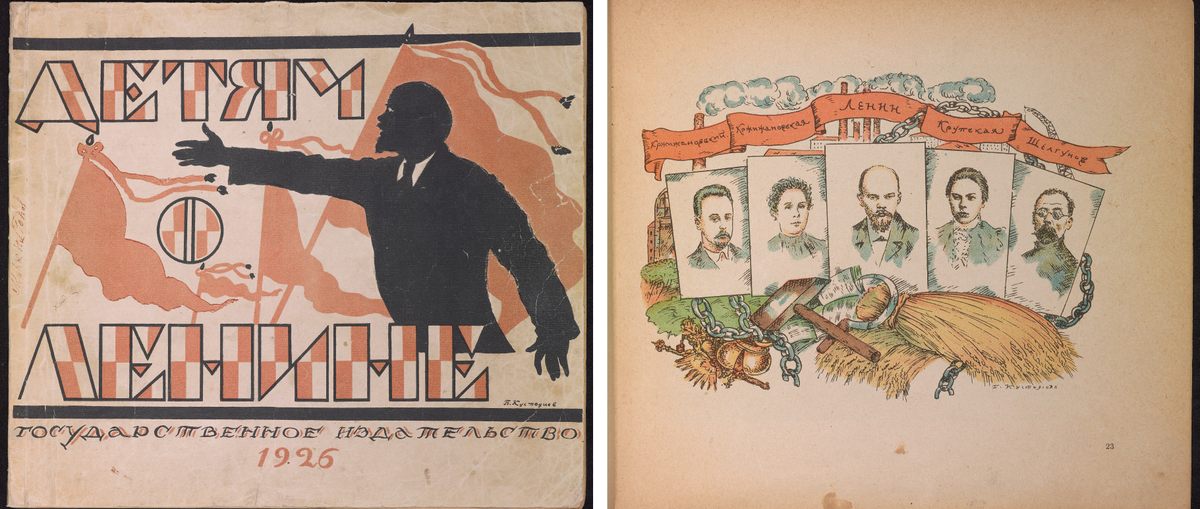

“Perhaps no 20th-century children’s books blur the boundaries between art and propaganda in such compelling ways” as early Soviet children’s literature, says Andrea Immel, Curator of the Cotsen Children’s Library at Princeton University. The Cotsen holds nearly 1,000 of these books, published between 1917 and the start of World War II. The collection demonstrates how then-new Soviet ideologies were communicated to the younger generation—even if the idea of indoctrinating children with colorful books wasn’t itself new.

“While it’s tempting to imagine that the Soviet experience was unprecedented because of the overthrow of the tsar, it is possible to find other historical moments when reformers or radicals believed that the key to a better future was to provide children with books communicating superior values,” says Immel, citing John Newbery, known as the Father of Children’s Literature. “In the 1760s, he published out of the conviction that English society was corrupt and that one of the best ways to turn the tide was to bring up children differently.”

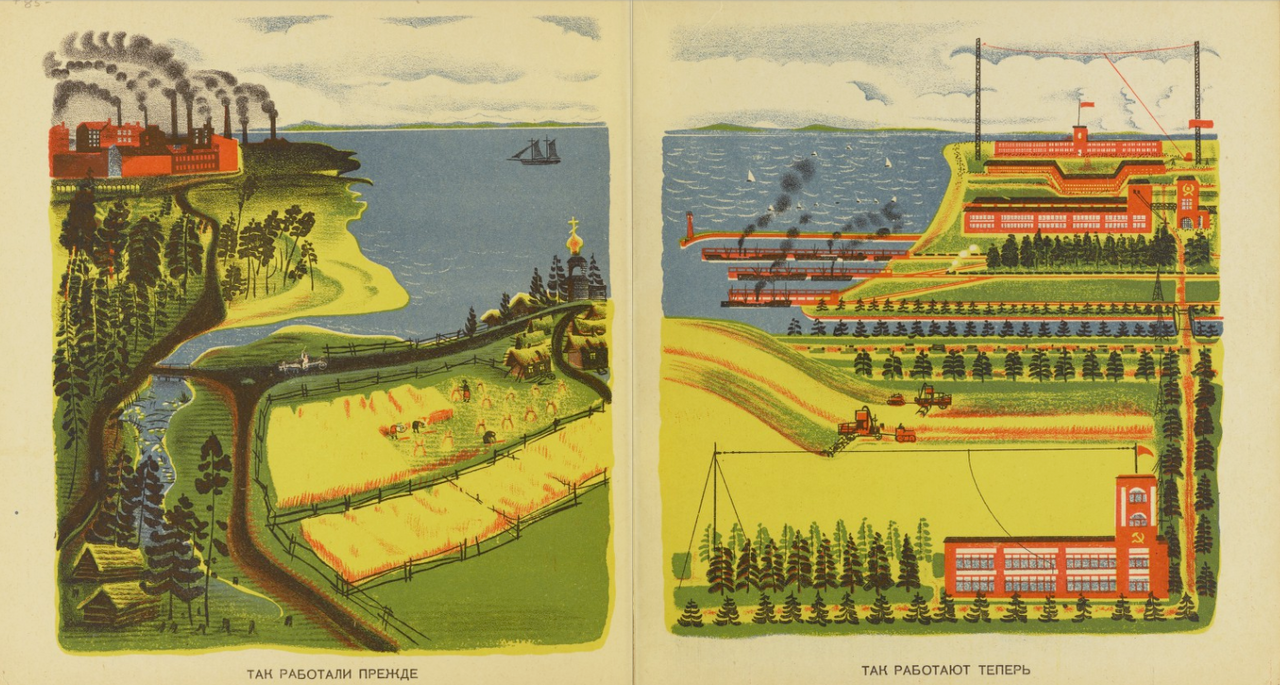

However, Immel notes, there was one crucial difference. “The Soviets were keenly aware of needing to leap ahead as quickly as possible, creating at the same time a new breed of men,” she says. “And so the tremendous artistic firepower that could be harnessed in the Soviet Union of the 1920s brilliantly made the hard, unglamorous work of agriculture or electrification heroic and patriotic.”

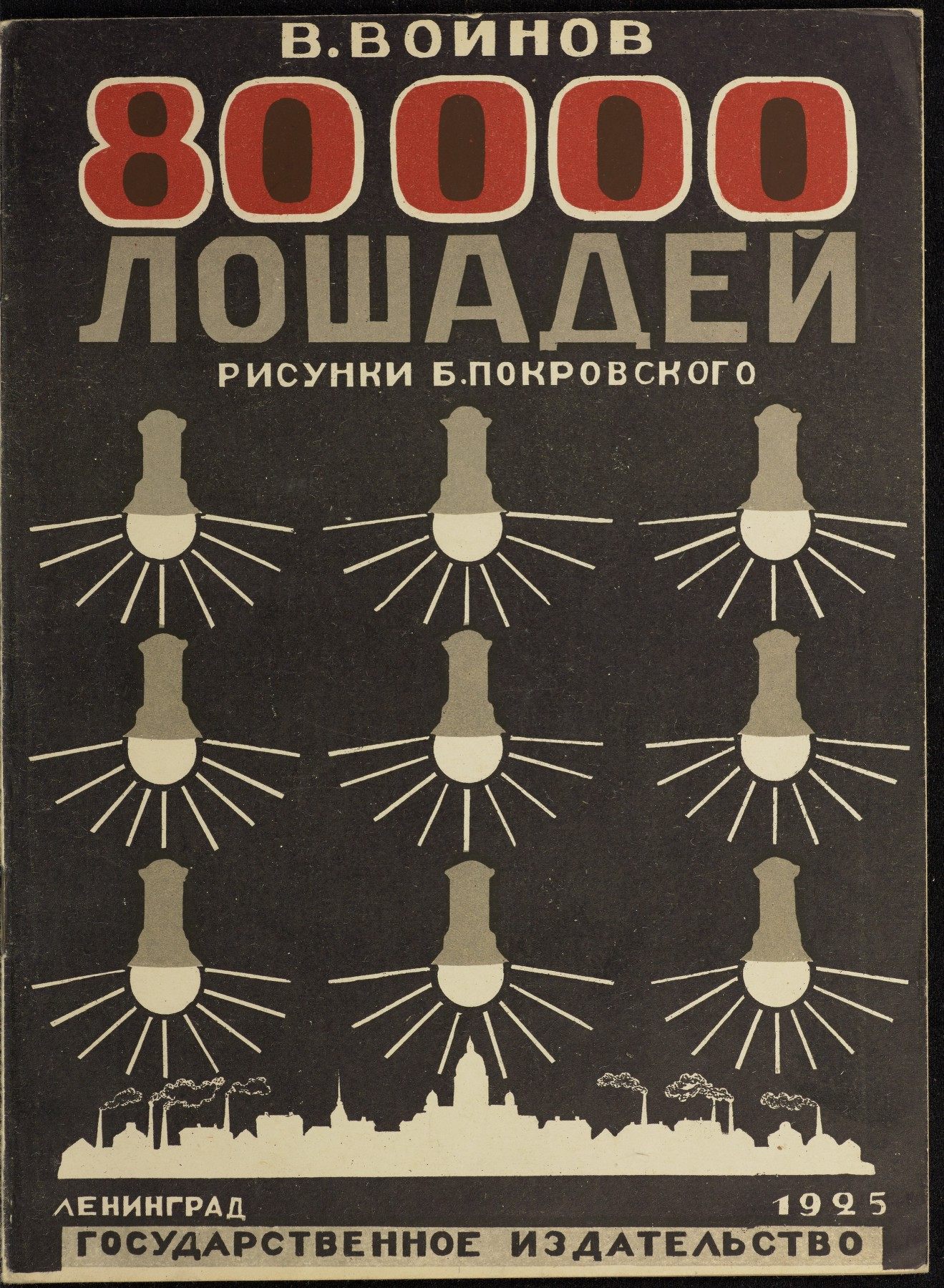

The shift away from filling children’s books with fairy tales was no accident. In their place, literature for children was focused on practical concerns and industry. The 1930 book Kak svekla sakharom stala (How the Beet Became Sugar) illustrates and describes the sugar production process: “Work is happening night and day. Night and day, sugar is being made from beets.” In 80,000 loshadeĭ (80,000 Horses), the story of the Volkhov Hydroelectric Plant—the first in Russia and named after Lenin—is told in rhyme. Some of the books even created work themselves. The 1930 title Shimpanze i martyshka (Chimpanzee and Marmoset) provides instructions on how the reader can make a toy monkey.

The readership of these books wasn’t limited to the Soviet Union either. Immel corresponded with a writer from Kolkata who fondly remembers books from the Soviet children’s publisher Raduga. In the archive Immel discovered Millionnyĭ Lenin (The Millionth Lenin), by Lev Zilov, in which two boys from India participate in an uprising against the Raj. They flee the country and have a series of adventures that take them to the Soviet Union. There, they watch a parade before Lenin’s tomb and don warm clothing (while retaining their turbans). “It had never occurred to me that Raduga books had been translated into South Asian languages or that South Asian people would be represented in Soviet children’s books,” Immel says.

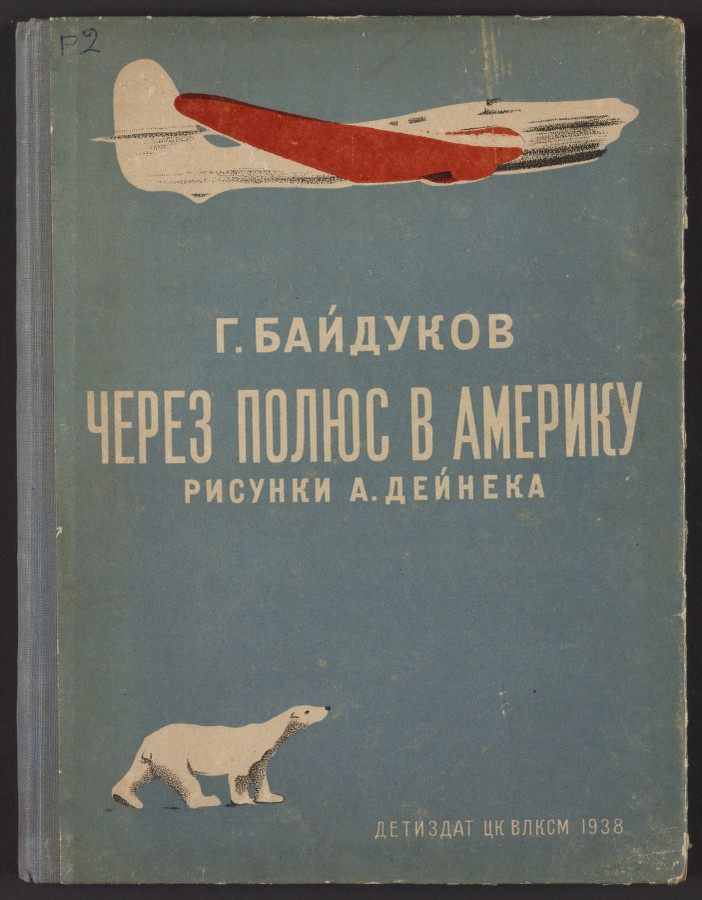

There are also books about glorious achievements, such as pilot Georgiĭ Baĭdukov’s nonstop flight over the North Pole in the mid-1930s. But by this time, there had been a political shift that changed the way that children’s books looked. Throughout the 1920s, the aesthetics of the books were diverse, and included the influence of the Russian avant-garde, including the work of well-known writers and artists. In 1934, the All-Union Soviet Congress of Writers declared that socialist realism was the only acceptable artistic style. Over the years, some writers and artists escaped into exile. Others did not.

In 1931, artist Vera Ermolaeva illustrated the book Podvig pionera Mochina (Mochin the Pioneer’s Heroism). In the story, a Young Pioneer—the Soviet Union’s more militaristic answer to the Boy Scouts—helps the Red Army in Tajikistan. But by the end of the decade, both Ermolaeva and the book’s author, Aleksandr Ivanovich Vvedenskiĭ, fell victim to one of Stalin’s purges.

Memories of Soviet children’s literature linger today. Immel recounts a story of a Russian colleague who visited her and spotted some Raduga pamphlets. “He knew exactly what they were, being old friends from his childhood,” she says. “He picked up the copy of Kornei Chukovsky’s Barmelai, illustrated by Mstislav Dobuzhinski, and began reciting it from memory.”

Atlas Obscura delved into the Cotsen’s Soviet literature holdings for a selection of children’s titles from the 1920s and 1930s.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook