This Annual Pipe Walk Maps a Medieval Tradition in Bristol

The St. Mary Redcliffe Pipe Walk honors a legal agreement dating back to the days of Richard the Lionheart.

The tradition is centuries old—possibly the oldest of its kind anywhere—but the dress code for the St. Mary Redcliffe Pipe Walk is more about practicality than pomp.

“Walking boots and outdoor clothes,” is the usual attire according to veteran pipe walker Bryan Anderson. Since the annual event takes place in October in Bristol, England, raincoats and umbrellas are also typical fashion statements—perhaps disappointing anyone hoping for some medieval cosplay to acknowledge the deep history of the walk, which may be more than 800 years old.

But then, the St. Mary Redcliffe Pipe Walk, honoring an agreement that dates back to the days of King Richard the Lionheart, has always been a no-nonsense, utilitarian affair.

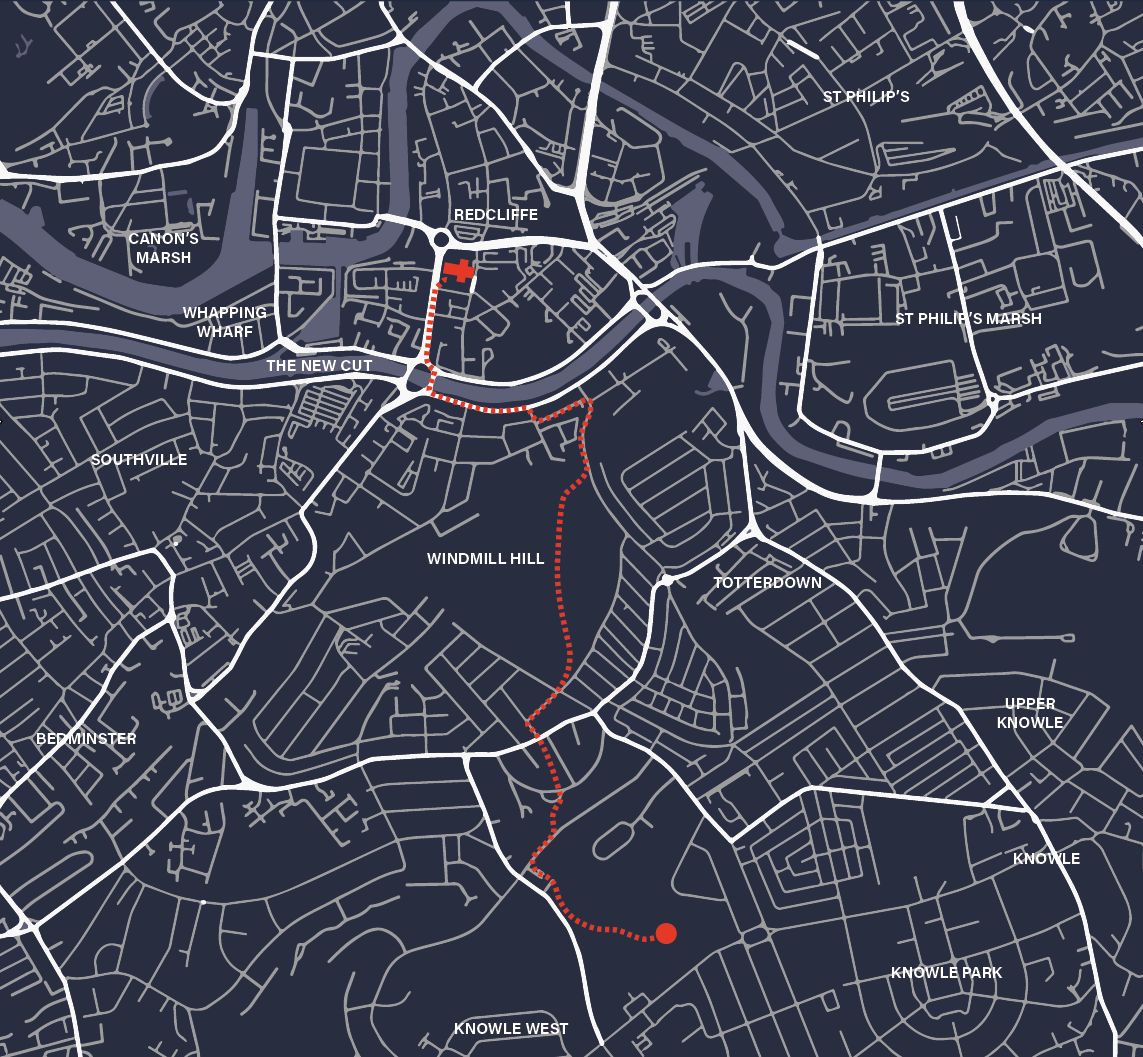

The mile-plus walk through Bristol’s south side follows the route of a medieval conduit that began piping water from a well to the parish in the late 12th century. It’s uncertain exactly when the first walk to inspect the pipe occurred, but it has become both a beloved annual ramble and a charmingly eccentric way to reconnect with history—even though the pipe itself has long been disconnected.

The parish pipe story began in 1190, when Robert de Berkeley, a knight of the realm and local benefactor, granted St. Mary Redcliffe—then a young and struggling parish—perpetual rights to the waters of the Ruge Well, a distant spring south of the church.

“There are no natural wells in the Redcliffe area,” says Anderson. “Without the pipe, there wouldn’t be a church, let alone a parish.”

More than water began flowing into the parish: The rights to the pipe included the lands between the well and churchyard, a nice fringe benefit that brought in steady income. “St. Mary Redcliffe is still pretty wealthy today… because of the revenue generated over the centuries by those ‘pipe lands’,” says Rhys Williams, the church’s heritage development manager.

The lands have since been sold off, but the church retains the right to “walk the pipe,” affirming its endowment and maintaining its right of way. The annual ritual starts in the most English way possible: with a cuppa.

“Before the walk, there’s tea and coffee at St. Barnabas church in Knowle,” which is located near the spring, says Anderson. The wellhead itself is inside a half-sunken, fern-filled stone structure that’s hidden among private allotments. Allotments are an ancient English tradition that goes back to Anglo-Saxon times, and the small parcels for growing food are usually off-limits to outsiders. The pipe walk is a notable exception.

The walk begins promptly at 10 a.m. when a padlock is removed from the metal grille in front of the well, which is hidden by a trap door. Participants raise the door and take a peek at the water while the parish priest blesses the spring.

With the waters sanctified and satisfactorily flowing, walk participants—usually St. Mary Redcliffe’s priest and a few dozen parishioners—set off on the (mostly) downhill route. The church’s impressive 274-foot spire is visible at points, a reminder of the finish line as they weave through the streets and greenways for 1.5 miles.

Waystones, some bearing the letters SMP for “St. Mary Redcliffe Pipe,” guide the walkers across fields and parks, along residential streets and bustling main roads—and even through someone’s backyard.

“Do they mind? No. They’re very amused that their backyard plays a small part in a centuries-old tradition,” says Anderson. “We like our traditions here. Bristol is that kind of place.”

Those traditions include “bumping,” a rite of passage for new pipe walkers that Anderson knows well. During his first pipe walk in 1968, after relocating from Kent to Bristol to become the choirmaster at St. Mary Redcliffe, Anderson himself was bumped: “Four experienced pipe walkers lift you up by the arms and legs, and gently bump your behind on one of the waystones,” he explains.

The bumping usually takes place in Victoria Park, a large green space about halfway through the walk. It’s not the park’s only connection to the historic pipe. There’s a spot where the St. Mary Redcliffe pipe intersects with 20th-century sewerage and, right above it, the local water company built a labyrinth to commemorate Bristol’s centuries of waterworks; the winding design replicates a pattern on a ceiling boss in the St. Mary Redcliffe church.

Just north of Victoria Park, the pipe’s route crosses the Bristol to Exeter rail line. In the early 20th century, pipe walkers reportedly had the authority to stop trains to make their crossing but, these days, they use a tunnel underneath the tracks rather than crawling up and down the rail embankment.

Throughout the walk, the church surveyor lifts manhole covers to verify the pipe is there and the water is flowing through it. The original wooden pipe is, of course, long gone, as is its lead replacement. The current conduit is a four-inch cast iron pipe, installed in the 19th century—around the time of the earliest written record of the pipe walk.

Despite the nearly 700-year gap between Sir Robert’s gift and the first recorded mention of the walk, the event is often billed as the oldest such custom known. The lack of documentation to support that claim is no cause for skepticism, however.

“If it was an ongoing tradition, there would have been no need to write it down. So it stands to reason that the parish observed the custom before that time as well,” says Williams.

In fact, because the walk was intended to ensure the pipe was intact and delivering potable water to parishioners, it’s probable that the tradition goes all the way back to the original grant.

More recently, major events have disrupted the annual inspection, and even the route itself. The New Cut, an artificial waterway built in the early 19th century to divert the River Avon, severed St. Mary Redcliffe from its pipe lands, and the course of the pipeline was altered to fit under the new Bedminster Bridge.

Little over a century later, the walk was abandoned, likely due to World War I, and was not revived until 1928.

Then came the Bristol Blitz. For six months beginning in November 1940, the Luftwaffe laid waste to much of the city. On Good Friday 1941, a German bomb sent a chunk of tram track into the St. Mary Redcliffe churchyard, where it remains embedded in the ground as testament to how narrowly the building escaped destruction.

The pipe, however, suffered a direct hit. A 1930s lion-headed fountain just inside the church gate on Redcliffe Hill, with its brass plaque thanking Robert de Berkeley for his gift, hasn’t spouted water since.

Williams says there are plans to fix decades-old damage and get the water flowing again all the way to the end of the pipe—not that it matters for the annual pipe walk tradition.

“After all, every house in Redcliffe now has tap water, just like everywhere else,” says Anderson. “Walking a pipe that doesn’t provide any water anymore may sound like a very eccentric thing to do. But then, we Bristolians like to think of ourselves as very eccentric people.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook