The Ecological Mystery of a Stink Bug Swarm Far Out to Sea

The chance encounter has led to insights on how insects make it to distant islands.

On a moonless night in spring 2014, a Brazilian Navy ship traveling to Rio de Janeiro from the Trinidade and Martin Vaz Islands paused in the open ocean, nearly 250 miles from the coast. The crew illuminated the white hull and deck with 10,000 watts of spotlights as it lowered a device to measure currents associated with a nearby underwater volcano. Minutes later, the ship was swarmed.

“It looked like shooting stars were flying straight at the ship from all directions, in relatively straight paths,” says Ruy Alves, a botanist who was on board the ship.

Hundreds of insects were incoming, with most crashing into the hull and dropping into the ocean. Alves and his colleague Nilber Silva scrambled to capture the few that landed on the deck. They used their bare hands and improvised envelopes from pages torn out of a field notebook. Though the botanists were on the voyage to study plants on Trinidade Island, a largely barren volcanic hunk in the South Atlantic Ocean, they knew that they were witnessing something potentially new to science.

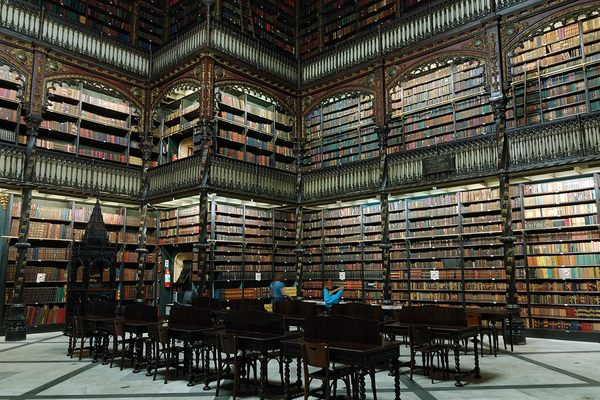

Upon their return to the mainland and the Museu Nactional, Alves and Silva contacted several entomologists to tell them what they had seen. The insect experts were astonished by the story they told.

Some insects, such as monarch butterflies, are widely known to migrate long distances, but they tend to avoid flying over big obstacles such as oceans. They prefer to stick to routes where they can take breaks to rest and refuel. Adding a further wrinkle to the night swarm at sea, these migrating insects also usually travel by day. “I think the fact that they were flying at night and on the open ocean is fantastic because both are uncommon,” says Angelo Pinto, an entomologist at the Universidade Federal do Paraná in Brazil. Pinto and his colleagues identified the insects collected from the ship’s deck: a dragonfly, three moths, and 13 stink bugs. All of the specimens were deposited at the Museu Nacional, where they were housed until 2018, when a catastrophic fire destroyed them, along with most of the museum’s 20 million artifacts and specimens.

For a dragonfly to make the trip over the water isn’t entirely surprising, given their penchant for long-distance travel. The species on the ship is known to cover impressive ground by gliding with its long, slender wings. But stink bugs are another matter. “They aren’t gliders like dragonflies,” says Pinto. “They have to flap their wings continuously to sustain flight.” He had never heard of a stink bug—shield-shaped insects belonging to the order of Hemiptera, or “true bugs”—migrating over open ocean. Either the stink bugs had actually been stowaways on the ship, or they had made an incredible, uncharacteristic journey.

There are nearly 5,000 species of stink bug all over the world. The ones familiar to most people today are brown marmorated stink bugs, native to Asia and considered a major invasive agricultural pest in the United States. The ones from the ship were actually giant strong-nosed stink bugs. Unlike the brown marmorated ones, these big bugs hunt other insects, using strong mouth parts to pierce their prey and suck up their internal fluids. The species is found all the way from northern Argentina to the southern United States and probably originated in South America.

Giant strong-nosed stink bugs are also found in the Galápagos Islands. Norwegian zoologist Alf Wollebaek discovered them there in 1925, nine decades after Charles Darwin’s famous visit aboard HMS Beagle. Wollebaek and the other members of his expedition arrived on Floreana Island on a yacht, aptly named Floreana, that was transporting Norwegian settlers. The Norwegians ultimately failed to establish lucrative fishing and whaling, but Wollebaek was decidedly successful in his collection mission—by the end of his five-month exploration, he had gathered more than 500 specimens, including tortoises, sea lions, birds, lizards, and several species of insect, including the introduced giant strong-nosed stink bug.

Since its discovery there, the bug has spread to three other islands in the Galápagos, but it’s not an alarming invasion, says Charlotte Causton, senior research scientist at the Charles Darwin Foundation. They aren’t nearly as troublesome as other alien insects in the archipelago, such as Philornis downsi, a blood-sucking fly that is annihilating the Darwin’s famous finches. According to a scoring system Causton devised to describe the threat level of non-native insects on the islands, the blood-sucking fly has the highest score, a seven, while the giant strong-nosed stink bug is a three.

Causton says the stink bug’s limited spread, to just four of the 19 islands “suggests that, at least in the Galápagos, it is a poor disperser and colonizer.” This is perhaps in part because it’s a weak flyer, according to Luiz Campos, a stink bug expert at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul in Brazil, with puny wings relative to its body size. The species wasn’t believed to be capable of flying the hundreds of miles from the mainland to the Galápagos Islands; scientists always assumed that people carrying exotic plants had brought them over.

So what were these poor-flying bugs doing hundreds of miles out in the South Atlantic? It was an ecological mystery. According to Pinto, the most plausible explanation—that the insects had boarded the ship in Brazil and come along for the ride—was quickly ruled out. “They saw the swarm of insects flying on the open ocean; they did not see the insects flying from the ship and coming back,” he says.

At the same time, the entomologists agreed that the stink bugs couldn’t have made the journey under their own power—so they must have had help. Small insects sometimes rely on the wind to carry them over long distances. In rare cases, large insects, even ones larger than the nearly-inch-long stink bugs—can get blown by strong winds—even across an ocean. “African locusts have been documented to reach South America assisted by heavy storms,” says Pinto, so it was possible that the giant strong-nosed stink bugs had gotten a natural lift.

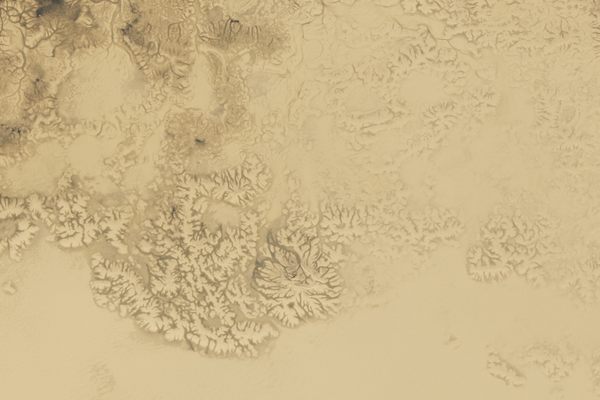

Pinto and his colleagues worked backward to reconstruct the path the stink bugs might have taken, accounting for the strength and direction of the wind that day—information that the navy ship had fortunately been recording. The data pointed to a stretch of the Brazilian coast as the swarm’s most likely starting point. With a push from the wind, the insects could have covered the 250 miles from the coast to the ship in as little as 34 hours, according to an analysis the researchers published in the journal PeerJ.

Campos, who was not involved in the report, says it makes a case for the role of wind in long-distance dispersal of large-bodied insects, something that wasn’t considered much of a factor before. But there are still unanswered questions. What prompted the insects to migrate in the first place? Where were they heading? Had they continued on their path, with a steady wind, another week could have put the swarm in Africa, yet none of the species that were part of the swarm have ever been recorded on that continent. Depending on their heading, they also could have run into winds blowing in the opposite direction, possibly right back to Brazil.

The discovery is also raising new questions about the arrival of the species in the Galápagos. “Our observation on the open ocean opens a new window to investigate how these insects arrived there,” says Pinto. Perhaps rather than hitching a ride on plants being carried by people, they might have blown over, just like the stink bugs on the ship.

“I think it could be a good alternative hypothesis to the classic plant transportation scenario,” adds Campos, though he notes that it’s still speculative.

“More research is necessary to confirm our conclusions,” Pinto agrees, but he believes that the chance encounter between a well-equipped ship and a wayward swarm is “a very very first step to understanding these insects’ migratory process.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook