Thailand’s Bhikkhunis Want Recognition and Respect

In a country with only a few hundred female monks in the Theravada branch of Buddhism, the lifestyle is quietly radical.

The Venerable Dhammavanna, a former journalist living in Nakhon Pathom province, about 30 miles outside Thailand’s capital, Bangkok, now wakes each morning at 5:30. First, she meditates, then has a breakfast of rice. Dressed in saffron robes, she tackles her morning work—cleaning, welcoming visitors, even attending to IT snafus. She dines again at 11, and then takes classes in Buddhist teachings in the afternoon before completing community service tasks and winding down her day with chanting. She lives at Songdhammakalyani Monastery under the Venerable Dhammananda, the temple’s most senior monk.

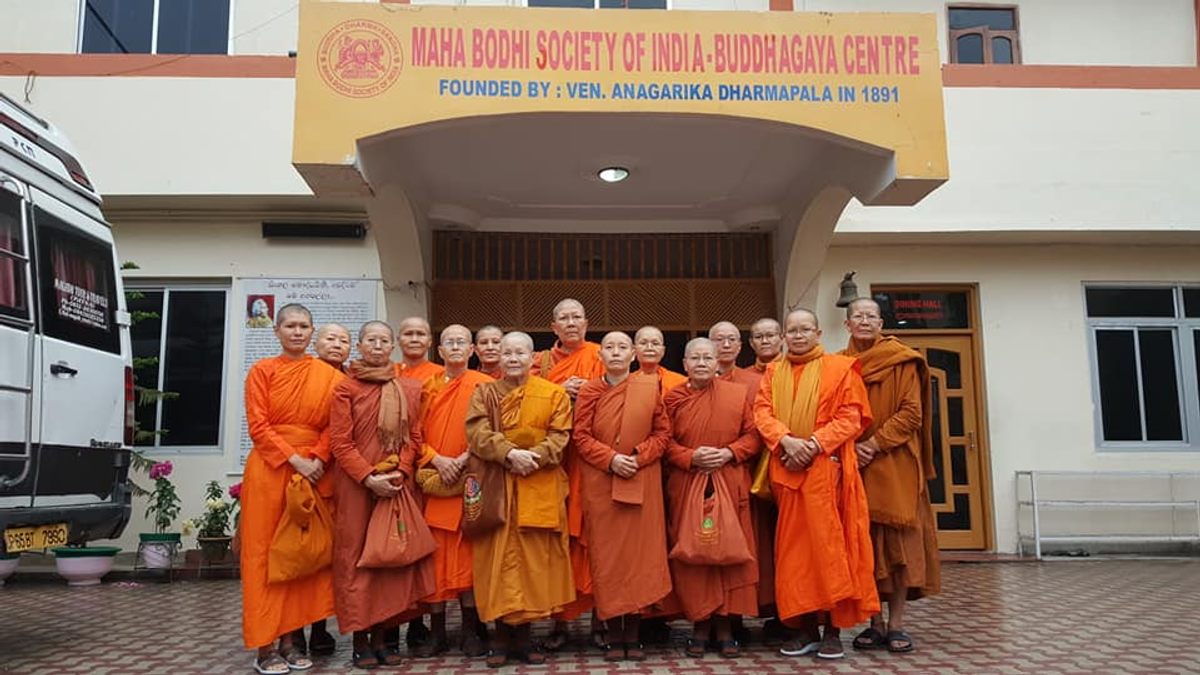

Ven. Dhammananda, born Chatsumarn Kabilsingh, is thought to be Thailand’s first female monk—called bhikkhuni—in the Theravada branch of Buddhism, which is dominant in Southeast Asia and Sri Lanka. The life of a bhikkhuni is subtly radical: In a country of about 300,000 male monks, Ven. Dhammananda estimates there are fewer than 300 fully ordained female monks in Thailand. Fifteen of them, plus three novices, reside at her monastery. All were ordained abroad, often in Sri Lanka or India.

Ven. Dhammananda, 76, flew to Sri Lanka to be ordained in 2001, after writing several books on women’s place in Thai Buddhism and teaching at a university. “One day when I was putting on makeup, suddenly I saw this person in the mirror and I asked myself, ‘How long do I have to do this?’” she says. From there, she started a movement: Now, an increasing number of Thai Buddhist women are seeking to become full-fledged monks despite having the option to become white-clad nuns, who follow a less-strict religious regimen.

Officially, only men can become monks in Thailand: The 1928 Sangha Act forbids the ordination of women. Efforts in the past by advocates to undo the 1928 order have been ineffective. The policy has been consistently upheld by the Sangha Supreme Council, the religion’s all-male ruling body that consists of the country’s highest-ranking monks. And while the bhikkhunis have found their community generally welcoming, they have still encountered resistance across the country from those who believe female monastics are illegal. Unlike male monks, bhikkhunis don’t enjoy, among other things, free train transportation or state funding for their temple. “It looks very much like a temple,” Ven. Dhammananda says of the monastery, “but officially it’s not considered one, so we get taxed.”

Though the Thai Constitution protects equal rights, these laws are difficult to change. It can be difficult to reconcile Buddhist law and state law, says Brooke Schedneck, a religious studies professor at Rhodes College who specializes in contemporary Buddhism in Thailand. And so the bhikkhunis get “whatever is the worst end of the stick,” she said, referencing their being caught between layperson taxes, and a lack of religious recognition from the council. Even so, most laypeople and ordinary monks seem to be essentially indifferent as to whether women can be fully-ordained, Schedneck says. Those who could actually change the 1928 law—“the oldest, very conservative monks” in the Council—are the ones clinging to what they see as “the purity of [a monk’s] identity,” she adds.

Over the past few years, the governing body and some other male monks have faced intense scrutiny over allegations of corruption, mass embezzlement of funds, and reports of sexual misconduct across temples. Meanwhile, female monks have carved out specific cultural niches. As Emma Tomalin, a religious studies scholar at University of Leeds has put it, “rather than rejecting religion for its inherent patriarchy, styles of ‘religious feminism’ have emerged.”

The monks from Songdhammakalyani Monastery, for example, deliver menstrual products to women in a nearby prison. (“People think ‘female monks, they must need these,’ but most of us are too old, so we have a surplus of them,” Ven. Dhammananda says.) Prison officers later asked the bhikkhunis to give ‘Dharma talks’—presentations of Buddhist teachings—to the female inmates, and the monks happily obliged. The incarcerated women have now come to see the monks as mother figures when they need spiritual guidance, Ven. Dhammananda says.

Describing an interaction with a pregnant inmate who asked for a blessing, Ven. Dhammananda says: “I was holding onto her, it was very moving. If I was a male monk, would I have been able to do that?” “The prohibition of close contact between monks and women and the sex scandals that have occurred in Thailand means that the presence of female monastic facilitates a more conducive atmosphere to relate to each other,” says Lai Suat Yan, a lecturer in gender and religion studies at University Malaya.*

“I don’t feel like people look at me as a stranger,” says Ven. Dhammaparipunna, who was born Sireerat Chetsumon. That was evident this past spring, when locals brought vegetables and hung bags of cooked rice on the gate surrounding the temple, to ensure that the monks inside wouldn’t go hungry. The monastics returned the favor, and distributed any extra food supplies on a weekly basis to nearly 200 families in the community. “Thai society is much more comfortable with bhikkhunis now,” Ven. Dhammaparipunna adds.

Ven. Niravani, a recently-ordained female monk in wire-framed glasses, thinks that Thai society and government will eventually have ample space for monks of all genders—it will just take time. And the bhikkhunis have another simple objective: “The media calls us ‘female monks,’” says Ven. Dhammananda, acknowledging efforts to show equivalence in status. “But, eventually, I think we’ll just prefer ‘monks.’”

*Correction: This story previously identified Lai Suat Yan’s institution as the University of Malaysia.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook