The Curious Gems of the River Thames

London’s riverbanks are filled with treasures, including scores of deep red garnets with mysterious origins.

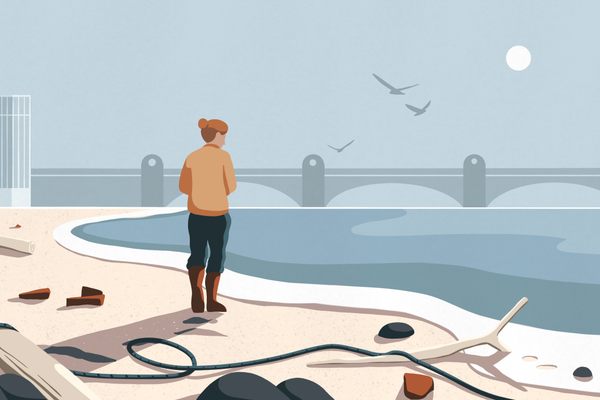

On the banks of the River Thames, when the tide is low, a person walking along the shore can see all kinds of things. With a keen eye, you can spot blue-and-white shards of 19th-century pottery, delicate stems of 18th-century clay pipes, brass buttons from coats, and coins dating back to the Romans. And if you look in the right spot on a sunny day, you might see something special: the wink of tiny, dark red stones, shining like pomegranate seeds against the pebbles. If you see these, consider yourself lucky—you’ve found one of the river’s little-known treasures: a Thames garnet.

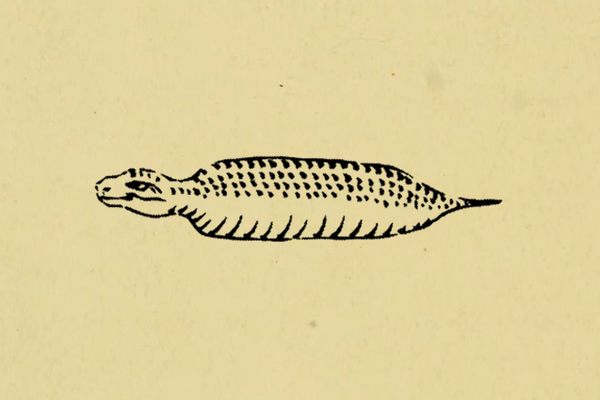

Thames garnets are varied. Some are raw stones with jagged edges and uneven shapes, but others are faceted, clearly carved and waiting to be drilled into beads or set into an earring, a bracelet, or a necklace. Their deep purplish red color is especially striking on the brown-gray banks of the Thames.

The most striking feature of Thames garnets, though, is that they shouldn’t be there at all.

There are gemstones native to Britain—agate in particular, and the famous Whitby jet used in Victorian mourning jewelry. But garnets are not mined in England, and while they “occur widely in the metamorphic rock of the Scottish Highlands,” according to the British Geological Survey, “most are too fractured, too dark in colour and too included for use as gemstones.” Beyond that, it’s hundreds of miles from the Highlands to even the northernmost parts of the Thames.

So, how did they get there? And why do they wash up seemingly only in a handful of spots, the locations of which are carefully guarded by the mudlarks who scour the Thames for lost items that wash in with the tide, rather than at random along the foreshore?

Some say they’re a remnant of industrial cleaning and polishing. One of the most abrasive forms of sandpaper is made from crushed and ground shards of garnet. Could Thames garnets have been the remnants of garnet paper production? It is ideal for sanding wood, and London was once a furniture-making center.

That’s probably not the case, though—at least not for all Thames garnets. After all, many Thames garnets are visibly faceted, and of uniform size, which paper-production leftovers wouldn’t be.

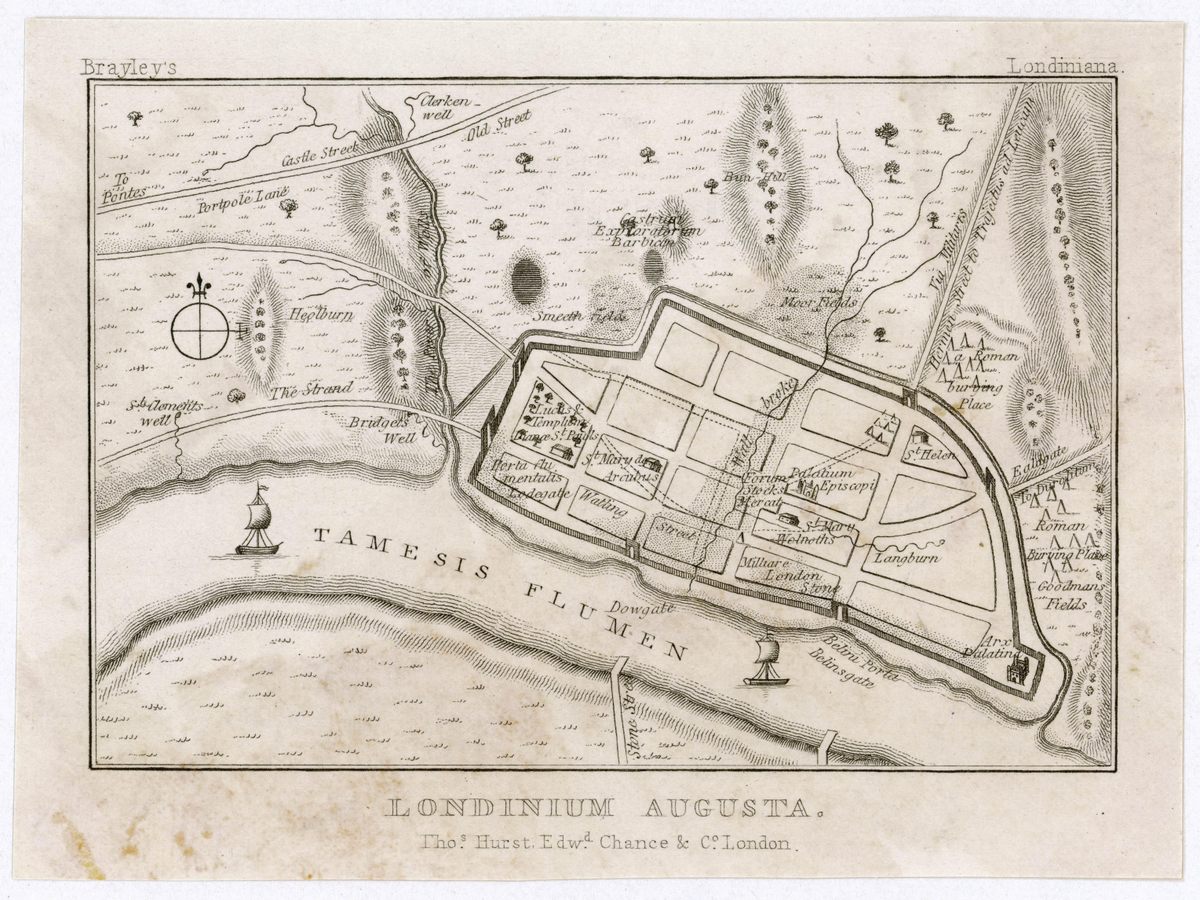

Well then, how about a nautical disaster? For most of London’s history, the Thames was used for trade. The Romans settled Londinium because of the natural port, and for centuries, the London docks served as a port of call for vessels from around the world. Could one of those vessels, carrying a haul of garnets, have capsized, leaving its cargo to churn through the river?

Academics have been tracing the garnet trade in Britain, which is thousands of years old, and there we might find clues. Archaeologist and Professor Helena Hamerow of Oxford University found through a national survey that garnets, a stone prized by the Anglo-Saxons, have been discovered in a “major concentration” inlaid into metalwork in grave goods dating back to the sixth century across the Thames Valley. With the stones not native to the valley, and before mass transit, garnets destined for London would have traveled by sea, says Hamerow, and then, by river. This means that garnets have been making their way to the River Thames for thousands of years. In all that time, plenty may have gotten lost overboard.

Only a few people are legally allowed to hunt for Thames garnets—or even remove them if they find them by chance. Mudlarks are among the few who are legally permitted to remove items from the riverbanks. To be a mudlark, you need a license, and in recent years, the British government suspended the issuing of new licenses for several years following a boom in applications during the pandemic lockdowns, leaving the already tight-knit mudlark community in a holding pattern.

Even among experienced mudlarks, Thames garnets are a prized find. Lara Maiklem, a mudlark and author, says that one of the only things we know for certain about the garnets is that they “aren’t native to the Thames,” but that theories of how they got there are far-flung.

Heather Stevens, known online as the Thames Wanderer, was one of the last to get a mudlarking license before the pandemic freeze, and she’s been combing the river’s edge ever since. “I went on to the foreshore one day with a friend just looking around and I took some stones home with me. I posted pictures of them on my artistry page, I was contacted by another mudlark via a private message who explained that I needed a permit in order to do mudlarking as the land belongs to the crown. Twenty minutes later I brought a permit.”

Stevens found her first garnets two years ago when searching the shore for Tudor dress pins. She initially dismissed them, thinking she’d seen shards of dark red glass. Only thirty minutes later, though, a fellow mudlark told her that she had actually stumbled upon treasure. “I was in total shock that semiprecious stones could be found on the foreshore so I have been collecting them in different forms ever since.”

Stevens’ favorite theory on the origins of the gems is that the garnets were the spoils of smuggling. From the 17th through the middle of the 19th century, smuggling was “rife in Britain,” according to the late historian Trevor May in his comprehensive Smugglers and Smuggling. In 1798, the Thames Police was established specifically because smugglers were costing the traders of London hundreds of thousands of pounds per year. Heavy import duties made smuggling an appealing way to get imported goods inexpensively, like fine wines, luxury fabrics, and gemstones.

Garnets would have been imported, and faced a nearly 70 percent import duty. Stevens speculates that when the stones were being shipped into London, “crew members on board docking ships would purposely push sacks of garnets … over the side of the ship to later come back and retrieve them at low tide.”

Mudlarks are legally prohibited from profiting from their finds—Stevens and others who find the garnets keep them, make them into jewelry, or gift them to friends. As for solving the mystery of where they come from? Garnets are “notoriously hard to date” according to Stevens. In her archaeological work, Hamerow could only date her stones via the surrounding metalwork, and the age of the gravesites they were laid in—meaning that even as the Thames garnets come to light, unadorned, they keep their secrets.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook