The 1925 Match That Ensured Pro Wrestling’s Future Would Be Fixed

Meet Wayne Munn.

It was 1925, and pro wrestling was big business. A throng of fans had packed themselves into a Kansas City convention hall, expecting to see champion Ed “Strangler” Lewis easily defeat Wayne “Big” Munn, a noted former NCAA football player. Munn was a newcomer to the wrestling world, and this was his first true test. Surely, fans thought, he would wipe the floor with the novice.

What the fans got instead was an outcome so unthinkable it created a buzz that shot around the arena. The air was electric. After less than 40 minutes, Munn had defeated the great champion, throwing him across the ring and out of it. It was a loss unlike Lewis had ever faced.

The crowd left that night in amazement, with an incredible story to tell: the night Wayne Munn beat Ed Lewis.

But there was a small problem.

“Wayne Munn couldn’t beat Ed ‘Strangler’ Lewis to save his life,” says Kyle Klingman, director of the National Wrestling Hall of Fame Dan Gable Museum in Waterloo, Iowa. “There’s just no way he could beat him.”

Everyone knows pro wrestling today is “a work.” A planned event. A show, no different than a television episode or film.

But it wasn’t always this way. Pro wrestling started in the world of legitimate sport, in the same way boxing did. Legitimate wrestling bouts sold out arenas across the country. In 1911, when Frank Gotch wrestled George Hackenschmidt at the newly-opened Comiskey Park, it was in front of 30,000 people, one of the biggest crowds in sports history at the time.

But professional wrestling began to change in a way unlike anything ever seen in sports history. While boxing had known to be fixed from time to time, and the “Black Sox Scandal” had briefly tarnished Major League Baseball, no legitimate sport had ever made the full transition into what the WWE now calls “sports entertainment”—fully scripted, predetermined matchups, with chosen champions.

That change didn’t happen overnight. But wrestling historians look to one match, which completely altered pro wrestling’s history: Lewis vs. Munn, Kansas City, Miss., Jan. 8, 1925.

“That really kind of put the stamp on it,” Klingman said. “This completely changed the landscape of professional wrestling.”

Pro wrestling in 2016 consists of larger-than-life characters performing gymnastic feats in prefabricated storylines with matches that have predetermined finishes. This is common knowledge, and honestly, it’s a lot of the appeal of modern professional wrestling. It’s evolved from a sport into more of an artform, where storytelling is paramount, both inside the ring and out.

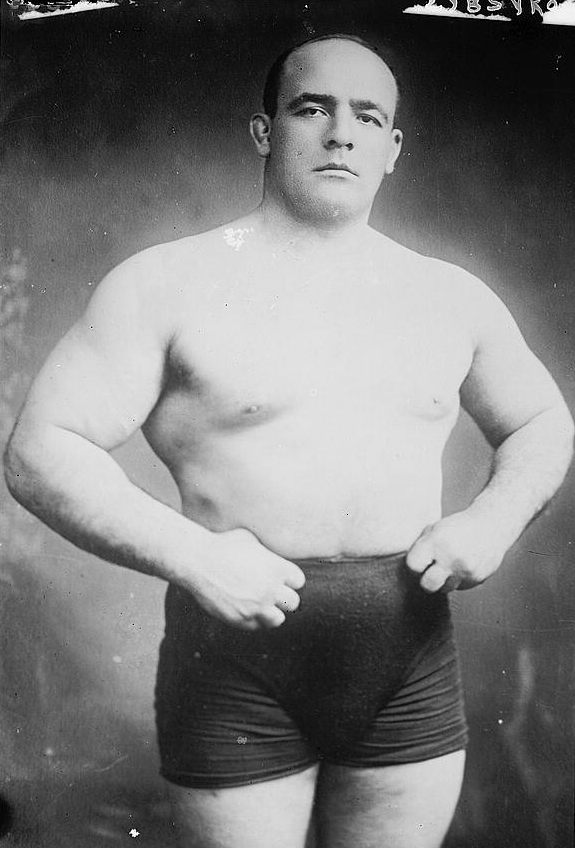

None of that was the case in the early 1900s. Wrestlers were known as “shooters” or “hookers,” skilled mat technicians who could beat nearly anyone in a legitimate fight. Moves weren’t anything spectacular. Ed Lewis was nicknamed “Strangler” because of his patented finishing hold: A headlock.

Not that it wasn’t an impressive headlock. Lewis was a pretty tough guy, and to practice his arm strength, he created a “headlock machine” that he would grind down on for long periods of time. And he was one of the most well-respected mat technicians in the world, having wrestled in more than 6,000 matches during his 44-year career and losing only 32 of them, according to the National Wrestling Hall of Fame. He was a tremendous draw, among the ranks of Babe Ruth and Jack Dempsey in the roaring ‘20s. To put it simply: Ed Lewis was the real deal.

Lewis was so good, in fact, that the matches were starting to get boring. Some could go on forever. Crowds dwindled, and paydays shrunk. In one 1916 match between Lewis and rival Joe Stecher, the match lasted five hours. The matches even received parody in popular culture: In a line from the “The Music Man,” Mayor Shinn notes he hadn’t seen Iowans get so excited for something “since the night Frank Gotch and Strangler Lewis lay on the mat for three and a half hours without moving a muscle.”

It was clear that something had to change, Klingman said.

“It was more of this legitimate style of wrestling, but these matches got unbelievably boring. I mean they were back-and-forth of just nothingness,” Klingman said. “At some point you say, ‘How are you going to make this more entertaining?’”

Lewis, his manager Billy Sandow, and their partner and fellow wrestler Joe “Toots” Mondt—known as “The Gold Dust Trio”—were keenly aware of this, and in 1925, went looking for their new star.

Wayne Munn was a big guy. So big that his nickname was, simply: “Big.”

In the 1936 book, “From Milo to Londos: The Story of Wrestling Through the Ages,” sports journalist Nat Flesicher lists the Kansas-born Munn as six feet six inches tall. He was a college football player at the University of Nebraska from 1916 to 1918, where he was known as “Nebraska’s giant.” Football came naturally to him, thanks to his size and unusual speed, and the school thought of him as “one of the most counted-on men on the team,” according to an old yearbook.

In 1917, Nebraska finished 5-2 and claimed the conference championship. Munn would have been a crucial part of the 1918 team, but left school to join the army. He was a lineman on the Camp Pike football team, and later, served in France before coming back to the United States to sell cars in Omaha.

The Gold Dust Trio saw Munn, and their eyes turned to dollar signs. He had the size, the body, the look—he was everything they wanted for their next star. He just wasn’t very good.

“Munn was a former football player with almost no wrestling background but he had huge name recognition,” said Mike Chapman, author of more than a dozen books on wrestling. “He was a big man, as his title would suggest. Nice looking. And people thought, ‘Here’s our chance to groom this guy, and make a little money off him.’”

Today, this is common. Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson, one of the most popular professional wrestlers of all time, started as a defensive tackle with the Miami Hurricanes, helping to win the national championship in 1991. Despite going on to become a WWE hall-of-famer, Johnson himself didn’t have any amateur wrestling background. But he was extremely charismatic, and beloved by fans. At the time, though, this was unheard of: Someone without real grappling skill had never been champion.

Munn agreed to the Trio’s plan. He would wrestle around the country, tallying wins against predetermined competitors in on the ruse. Later, he would meet Lewis, who would drop the belt. The big payday would be the rematch.

Lewis, for his part, was fine with losing the belt.

“Ed really did love wrestling, but everybody knew he was the best,” Chapman said. “He wasn’t worried about what the insiders thought, because everybody knew. And he wanted to make a lot of money.”

The one thing he wouldn’t do was lose clean. So the Trio put together an elaborate plan, and on Jan. 8, 1925, the match would get underway in Kansas City, with the winner of two out of three falls taking home the title.

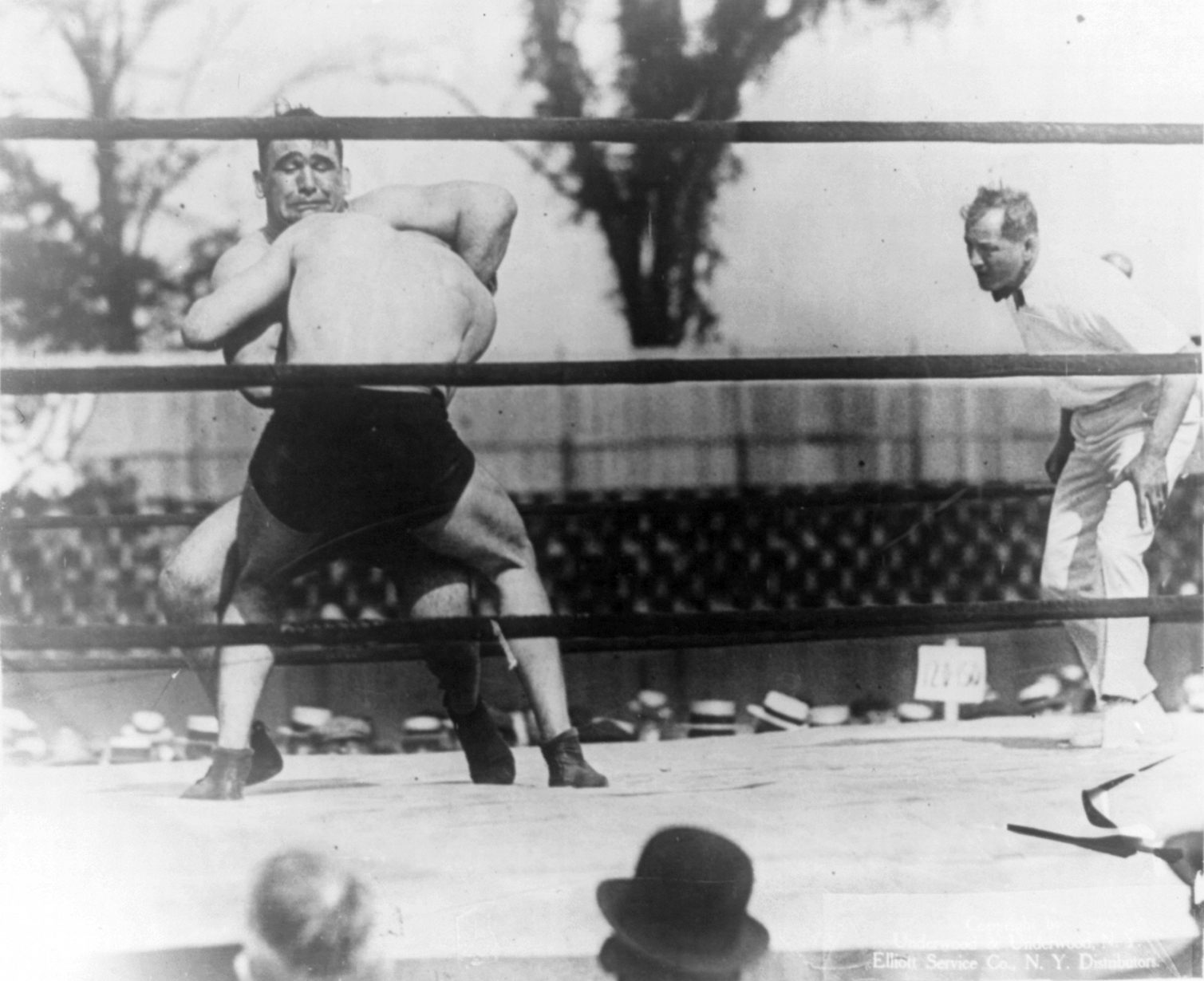

When the match started, it truly didn’t seem like Munn could beat Lewis. Munn had the brute strength, but Lewis was clearly the better wrestler. Yet whenever Lewis would apply a hold, Munn would muscle out of it. Even the patented headlock didn’t work.

To fans’ astonishment, the former football player held his own throughout the match, utilizing a signature football tackle before lifting Lewis high into the air and slamming him to the mat and pinning his shoulders for the first fall at 21 minutes.

Soon after, the two locked up again. This time, Munn lifted Lewis high into the air, and dumped him outside the ring. The crowd was stunned. None of this seemed possible against the great Lewis, but here it was happening in front of their very eyes.

The referee gave the second fall to Lewis, claiming that Munn illegally threw his opponent out of the ring. Sandow pleaded with the ref to end the match and make Lewis the victor. This was illegal, he argued, and his wrestler was injured. The referee didn’t oblige, but gave Lewis 15 minutes to “rest” and come back.

Come back he did, again feigning the injury. Munn quickly lifted Lewis, slammed him again to the mat, and won in less than a minute.

The crowd was ecstatic. They had been rooting for the good-looking footballer to defeat the predictable champion, and had gotten their money’s worth. Lewis was “hospitalized,” and there was word he may never wrestle again.

The Gold Dust Trio had solved two problems: They’d figure out a way to get Munn over despite his lack of wrestling acumen, and they figured out a way for Munn to lose in a way that wasn’t a clean victory.

They didn’t count on problem no. 3: Stan Zbyszko.

Munn would go on a championship tour, defeating Mondt himself, along with Mike Romano, Pat McGill, Wallace Duguid, and Stanislaus Zbyszko. Of all of them, the 46-year-old Zbyszko was the most talented, albeit on the older side.

Zbyszko was a strong wrestler, 5 feet 8 inches tall and 260 pounds. “The King of Poland” spoke 12 languages and had a law degree from the University of Vienna. But his one true love was wrestling.

“He was a gifted man. He could have done anything else,” said wrestling historian John Rauer. “He could have been a politician, he could have been a lawyer, he could have been a judge. But he loved the sport.”

Zbyszko was one of Munn’s first title defenses, and lost to the big man on Feb. 11 of that year in two straight falls, lasting less than 30 minutes total. He was later picked for a rematch on April 15.

During that time, the New York Times reported on Lewis’ condition, as well as a court battle between Lewis and Munn, which was likely entirely planned: Lewis refused to surrender the belt, arguing the match was wrestled under protest.

Munn, meanwhile, was living the life. The same month he won the belt, the Nebraska House voted to honor him for his victory. He received a $100,000 offer to tour Europe. In a publicity stunt, Munn, the untrained grappler, “taught” 1,000 students at Harvard how to wrestle. All of this was building up to the big rematch with Lewis.

On the day Munn had his second bout with Zbyszko, all seemed to be going well. Zbyszko agreed to lose again, and the match would boost Munn’s prestige going into the Lewis fight.

But when the time came, and they stood across from one another, Zbyszko reportedly smiled and said to Munn: “Tonight, we wrestle.”

It was a disaster. Zbyszko legitimately pinned Munn in practically every way possible. The referee, who was in on the finish, refused to count, but fans noticed and screamed for a pin.

After the first fall, Munn’s manager had to think quick. He claimed the wrestler was sick with acute tonsillitis, and tried to talk Zbyszko and the State Athletic Commission into allowing Munn’s sparring partner to finish the match. But it was to no avail.

There was nothing the referee could do. Either he would count the falls, or reveal the “work.” After mere minutes, Zbyszko defeated Munn, took the title, and left the former football player without even his dignity.

“Munn was spoiled by the greatest double cross in the history of professional wrestling,” Rauer said. “There may have been more devious double crosses, but not on such a large national stage, and not with such towering personalities involved as Zbyszko and Lewis.”

Part of the problem was pride. Zbyszko and others objected to the fact that a non-wrestler wore the championship belt. To them, whoever held the title had to be respected by their peers. Munn the football star wasn’t.

Fans didn’t know what to think. Why couldn’t this man, who so handily defeated Ed Lewis, hold his own against Zbyszko? It was a huge blow to Munn’s ego, his reputation, and the business.

“That exposed him,” Chapman said. “As easy as Zbyszko whipped him, it’s tough to talk that away.”

What followed was a series of negotiations and fights, before Lewis finally legitimately brought the belt back into the Trio’s hands. Lewis again fought Munn, this time defeating him easily. Munn’s star was no longer on the rise.

Had Wayne Munn been born 100 years later, he could have been the next Rock. But in the 1920s, in a world of “real” wrestling, he was never the same again. The Gold Dust Trio used him, they all made some good money, and when he wasn’t a draw for them anymore, he left the business.

As for pro wrestling, it kept evolving. Characters became more prevalent, as did the idea of the “heel” and the “babyface”—the bad guy and the good guy. The rivalry, the rematch. Munn’s reign as champion is largely forgettable, but his impact is still felt.

“That did, for all intents and purposes, change the game overnight,” Chapman said.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook