Looking for the Perfect Onion

From Georgia to New Zealand, the quest for a sweet, painless onion continues.

From The Core of an Onion: Peeling the Rarest Common Food – Featuring More Than 100 Historical Recipes by Mark Kurlansky, on sale November 7 from Bloomsbury Publishing. Copyright © Mark Kurlansky, 2023. All rights reserved.

With the exception of a few specialties such as cipollinis, small flat onions from the Emilia-Romagna region of Italy, or local varieties from certain regions, most consumers in the world know little about what onion they are eating. They choose large or small; yellow, white, or red.

But there is a tremendous variety of onions. Recipes can be deceptive, because some onions are stronger than others. Climate and soil—especially sulfur content and drainage—and, according to some, even phases of the moon, can have a tremendous impact on the nature of an onion.

For centuries, bees and other pollinating insects randomly crossed onions. But this was not a regular event. The onion produces what is known as a “perfect flower,” a flower with closely knit male and female parts that can pollinate itself and doesn’t need bees to reproduce. This produced only a few inconsistent variations. Even when nature produced a crossbreed, it was not striving for a trait that would be of interest to humans.

However, today 90 to 95 percent of onions produced in the United States are artificially mixed strains. Such hybrids originally had very low yields. But this began to change with the work of an Arizona geneticist, Henry A. Jones.

To create hybrids, a flower that was only female and thus was receptive to outside male input was necessary. Otherwise the flower favored its own organisms. Scientists worked at “emasculating onions”—removing the male parts. Since male and female parts were very close together, emasculation was a tedious and demanding effort performed with tweezers. The breakthrough came in 1925 when an Italian red onion was found in the University of California Davis plot that had only female parts and therefore could not pollinate itself. According to Jones, “the history of practically all hybrid onion seeds produced in the United States today can be traced back to [this] single male-sterile (female) onion plant … in 1925.”

Once able to create hybrids, Jones found that at least some of their offspring had female-only flowers, which enabled him to continue crossbreeding. From 1925 to 1943, using flies for pollination, Jones developed crossbred onions with a higher yield per acre, uniform plants and bulbs, and greater resistance to disease. Some of his onions were three times the weight of the original bulbs from which they were bred. He headed research at the Desert Seed Company in El Centro, California, which became one of the leading sources of onion seeds for American farmers. Once hybrid seeds became easily available, commercial farmers never again relied on the vagaries of their own seeds, but were able to buy exactly what they wanted.

Onion seeds are small, black, and triangular; they look like little shards of coal. Usually these little black seeds are planted in seedbeds and a farmer knows that the seedlings are doing well when they produce roots at least as long as the green shoots produced on top. Once they have substantial roots and shoots, they are planted in the field, usually about one foot apart. Any closer would inhibit the growth of the bulb.

In the 1930s, experiments in breeding onions began in Texas with cooperation from Jones. The “Grano 502” variety was developed. The original Grano came from the town of Grano near Toledo, Spain. The Texas Grano 502 is the parent of a growing American market, the “sweet onion.” These are onions that are less pungent, less stinging to the eyes, and contain more sugar, so that they are literally sweeter tasting. From these come the Texas supersweet and the Granex, similar to the Grano, but with a flatter shape.

In 1932, Moses Coleman, a farmer in Tombs County in southeastern Georgia, was looking for a good cash crop and decided to try onions. He bought Bermuda onion seeds from Texas. This was before Grano and Granex were developed. He harvested a crop in the late spring and was surprised to find that they lacked the characteristic aggressive bite of other raw onions. They were sweet-tasting and barely caused a tear when he cut into one.

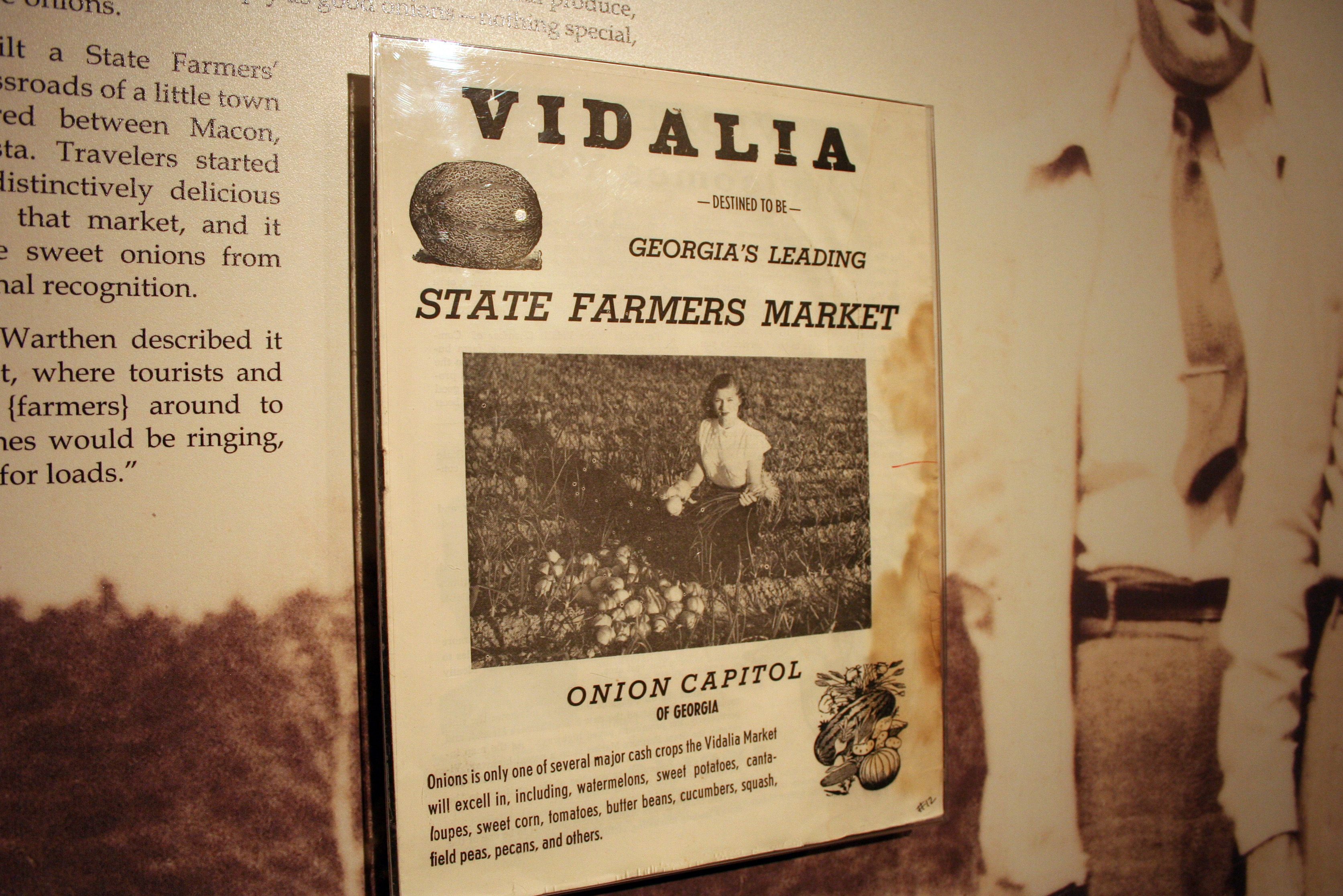

At first people didn’t want to buy them because they were not what an onion is supposed to be. But he found his market, and even sold them for a higher price than normal onions. This was at the height of the Depression and other struggling farmers noticed Coleman’s success and started growing these sweet onions too. The sandy soil with a low sulfur content, just the right amount of rainfall most years, and warm temperatures produced mild onions. In the heart of this region was the town of Vidalia, where major routes intersected. In the 1940s, a farmers’ market was built there by the State of Georgia. The sweet onions were the most popular product of the market and they became known as Vidalia onions.

In 1952, Texas Granex seeds were brought in and they became the standard Vidalia seed. As production increased, the State of Georgia took an interest in branding the product. To be called Vidalia onions they had to be grown either within 13 counties or parts of seven others—a distinct geographic area, about 10,000 acres in all, stretching from west of coastal Savannah to McRae in the center of the southern end of the state. Ideally, each field is rotated with another crop every other year, usually soybeans or peanuts.

A typical Vidalia onion farm is 300 to 400 acres but there are a few that are over a thousand. A few family farms have only 50 acres. But these sweet Granex hybrid onions are not suited for large-scale production because the higher the sugar content, the more fragile the plant, so these high-sugar onions require careful handling. There are about twenty-five varieties, but they are all flat shaped. Some would prefer a rounded onion like a Grano, better for slicing for such popular dishes as onion rings. But a Vidalia has been defined. It is a sweet, flat onion. Every year the Georgia Agricultural Commission states an official “pack date.” An onion sold before that date does not have the legal right to be called a Vidalia onion.

It is an expensive onion to produce, given that it is planted, harvested, and cured by hand. The seeds themselves are expensive. And they do not get the enormous yields of some of the western onion fields in Washington, California, Arizona, and Texas. A certain amount of pesticides is used depending on the year, to defend against crickets that move in right after planting and the attack of certain deadly pathogens. Irrigation is used to get the right amount of water. Too much water or not enough water will destroy the crop. After harvesting, the onions lie between five and seven days curing in the field unless it rains, and then they must be quickly moved to well-aerated drying pens, another reason why large holdings are more difficult.

Bob Stafford, former director of a research and promotion organization called the Vidalia Onion Committee, said, “It takes a certain kind of person to handle the rough times.”

Even so, Vidalias have become a big business, with about 200 million pounds of these hand-grown onions sold around North America annually. Marketing became more elaborate, with an annual onion festival to attract tourists and even a Vidalia Onion Hall of Fame that elected one inductee each year.

People in south Georgia know their onions. While most Americans are just choosing which color, in Vidalia country, customers have favorite farms. Some farmers are more conscientious than others. Conscientious means a better product but often less profit. Stafford said, “Some people pump them up with a lot of fertilizer to grow fast and they won’t be as sweet and mild. The only way to test them is to bite in.” Some prefer them a little stronger and others a little milder. You have to know your farm. Some say they like an onion that won’t even sting your eyes, but Stafford said that there will always be a little sting. “An onion is an onion.”

The expression “no pain, no gain” is not always true in cooking, though it often is. There is a constant attempt to get the onion without paying the price, i.e., tears. That is why onion powder, ground dehydrated onions, was invented. It does not make you cry, but it does not make you sing. It does not have the strong flavor we love in onions. Some chefs find it useful for certain dishes, the same way Indian chefs sometimes use dry ground ginger. Paul Prudhomme, the late New Orleans chef, on occasion used onion powder in combination with fresh onions, saying that the combination could make “the final effect more balanced and interesting.”

The claim of Bob Stafford in Vidalia that there will always be some bite because “an onion is an onion” may not always be true. Scientists in New Zealand and in Japan have been developing a new species that does not have the ability to produce tears. Scientist Eric Block reported that they had “a wonderful, fresh, sweet onion aroma.” Supposedly it will be oniony without the pain. But will that be an onion?

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook