The First Campaign Websites Were Just 2 Tech Guys Trolling Bob Dole And Bill Clinton

In 1996, presidential campaigns didn’t even think to register domain names.

The 1996 Presidential campaign button for Bill Clinton and Al Gore. (Photo: Quartermaster/background color altered/CC BY-SA 3.0)

In 1996, even before presidential campaigns had really gotten online, websites making fun of them had already appeared on the internet.

It started with Phil Gramm, the turtle-like Texas Republican who boasted that even his wife thought “Yuck!” when she first met him. Gramm’s campaign did have a website, an incredibly simple and self-serious affair. To two twenty-something tech guys in San Francisco, it looked like a parody, and it gave them an idea. Since almost none of the other campaigns had even bothered to put up a website yet, perhaps this was an opportunity to make good use of certain unclaimed domain names.

“We got Buchanan’s first,” says Brooks Talley. “Then we went on a spree.”

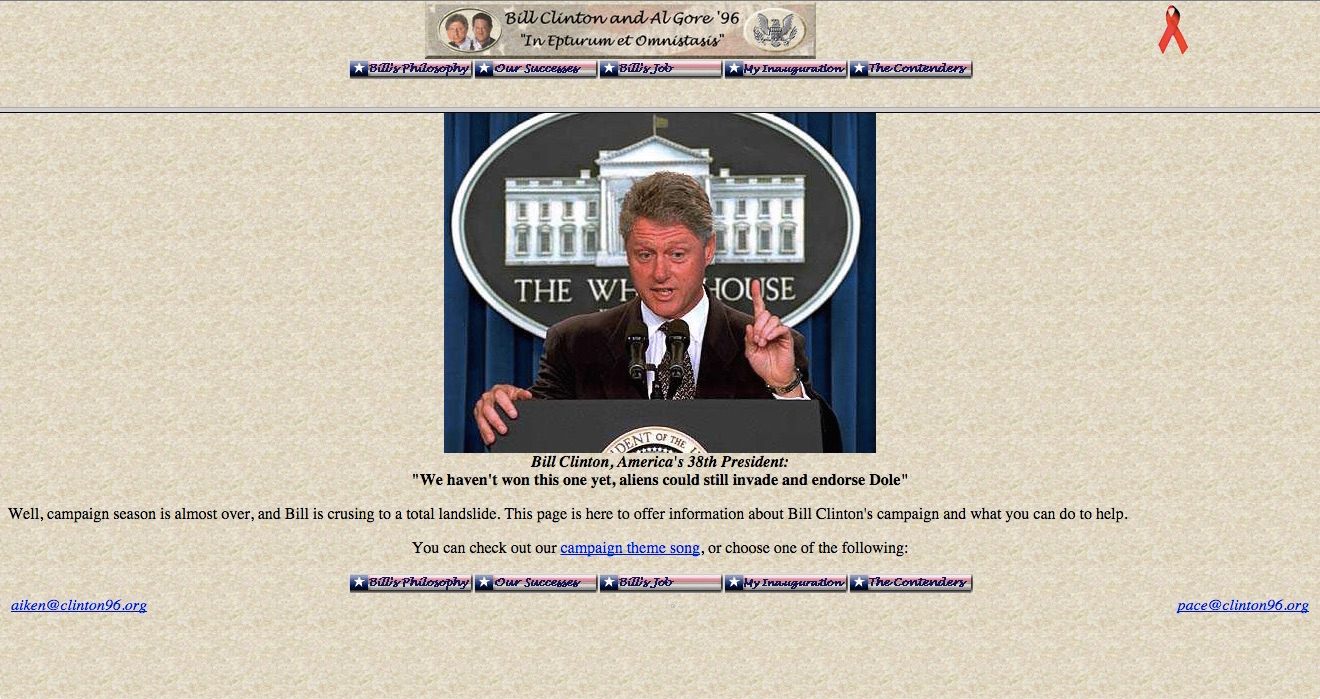

Soon, Talley and his friend Mark Pace had control of key political domain names, including dole96.org and clinton96.org, that could easily be mistaken for the addresses of real campaign sites. They even got ahold of whitehouse.org, on which they featured a photo of then-President Bill Clinton and a quote:

“We haven’t won this one yet, aliens could still invade and endorse Dole.”

www.whitehouse.org, circa 1996 (Image: Brooks Talley and Mark Pace)

A fake internet site was a new type of joke, and creating one was simple. Besides Phil Gramm, none of the candidates had bothered registering domain names, and ’90s websites were easy to slap together in a few hours, says Pace. Talley and Pace mercilessly lampooned the candidates, and though their spoof websites were obviously jokes, some of the fun came at the expense of naive people who did not yet have the instinct to ask, in the face of unbelievable web content–is this actually real?

You might say Talley and Pace were trolling the candidates, but their intent wasn’t malicious. They were more mischievous pranksters, who had tools at their disposal that no one had yet thought to use in the great American tradition of skewering politicians.

The public web was only about five years old, and in the previous election cycle, no presidential campaign even had a website–the 1992 Clinton campaign had been posting its policy papers to CompuServe forums. In 1995, when the first spoof campaign sites went up, the internet was still new and weird enough that campaigns weren’t paying that much attention to it.

By the end of the decade, in the 2000 campaign cycle, online campaigning would be important enough that the Library of Congress began systematically archiving campaign sites. But in 1996, winning the web was not a political priority, and Talley and Pace created a spoof website for Clinton and Gore more than half a year before the campaign launched its own.

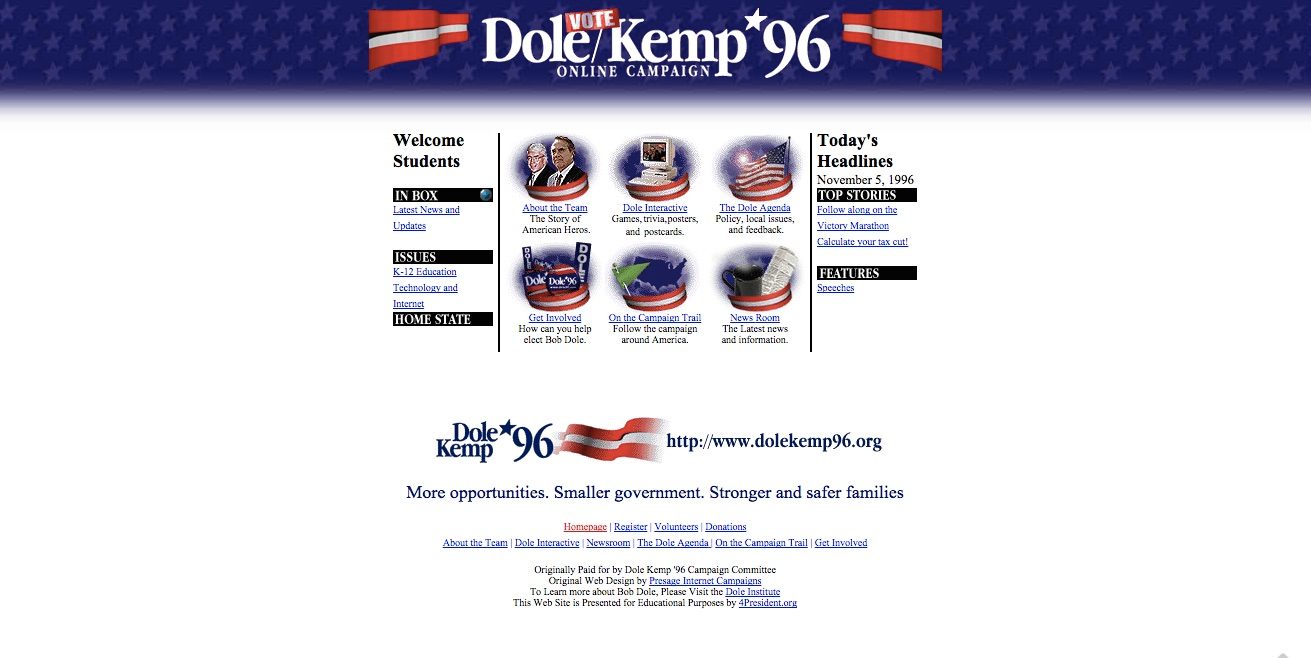

Dole’s actual campaign site (Photo: 4president.org)

Talley and Pace had a major first mover advantage. They were tech nerds, at a time when most people were just starting to use the web. Talley had dropped out of college and was making good money in the tech industry, and Pace was working 60 hours a week for a systems integration company and pushing hard to convince clients that they should get e-mail. The two men had met in the ‘80s, at an after-school job working in a stereo store’s new computer department. They shared the same sense of humor and taste in music; at one point they created a company that provided lighting for all-night raves in the desert.

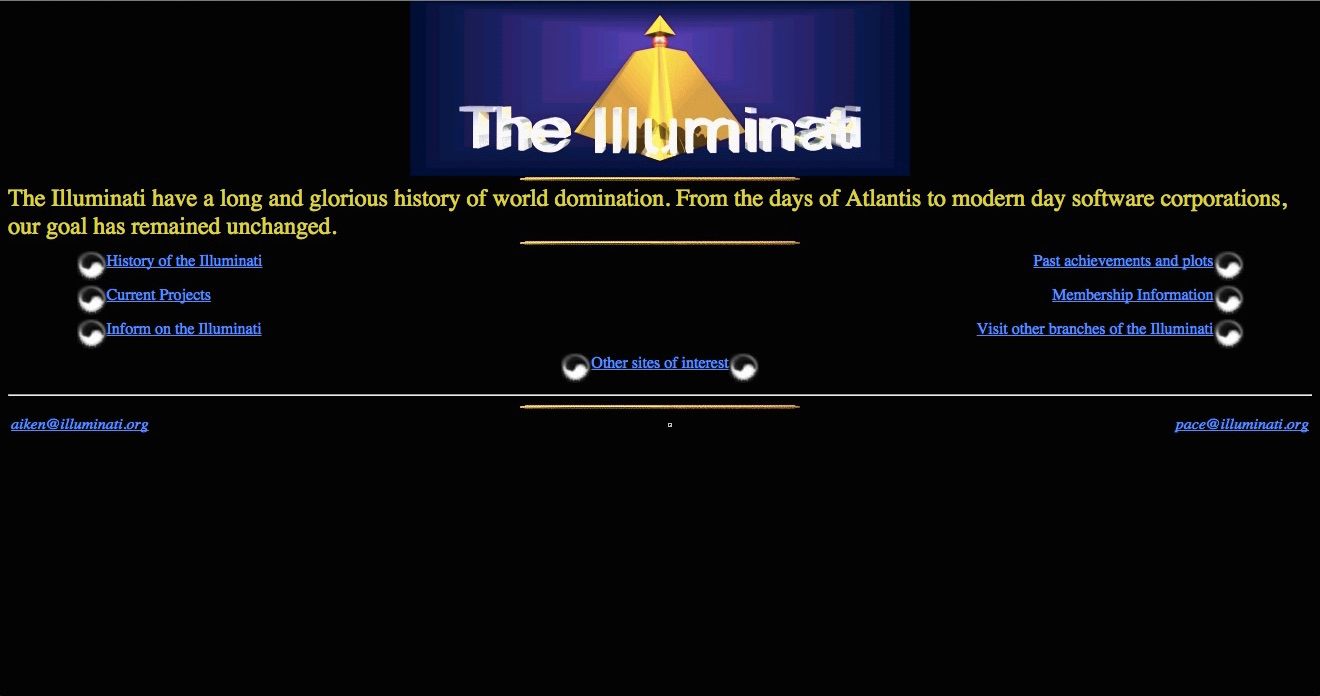

The political domain names they grabbed were part of a much larger collection. In the mid-90s, registering a domain was free: you just emailed InterNIC, a governing body for the internet, and about a week later, they’d grant you control of your new domain. Pace and Talley had registered hundreds, including Pigs.com, which they later sold to a pig farmer, and Microsnot.com, “the worldwide leader in hype.” At the time, they were really into The Illuminatus! Trilogy, a work of fiction by two Playboy editors about how conspiracy theories can invade culture, so they registered illuminati.org.

They’ve held onto that one, and while these days the site doesn’t load anything, it once had a certain weird glory to it:

Why wouldn’t the Illuminati have a website? (Image: Brooks Talley and Mark Pace)

“We liked wacky, surreal humor,” Talley says, and politicians who took themselves seriously were fun to poke fun at. The two young men photoshopped Bill Clinton into a photo of the industrial goth band Skinny Puppy. They imagined that Dan Quayle had defected to the Democratic Party.

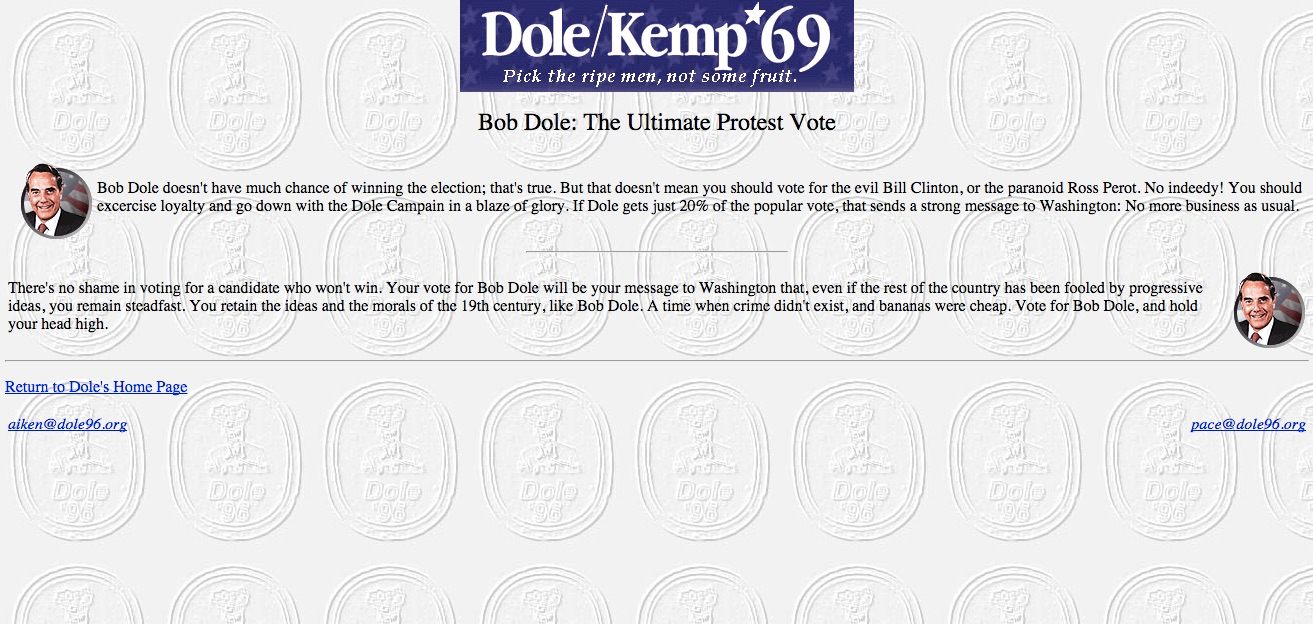

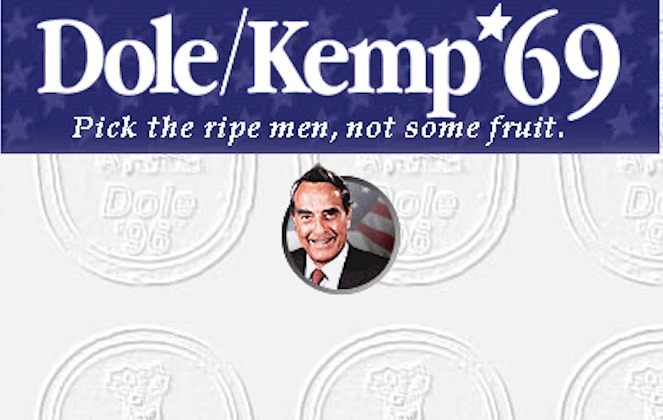

They riffed extensively on the idea that Bob Dole–“a sensitive, caring man (even kind of mushy like two-week-old bananas)”–was somehow connected to the Dole Fruit company, and their picture of Bob Dole speechifying at a podium labeled with the Dole Fruit logo earned them a cease-and-desist letter from the company. The tagline for the Buchanan site was: “Pat Buchanan is not a Nazi.”

“The Buchanan one was the creepiest,” Talley says. “We had a number of swastikas and Nazi references, and the copy was devoted to explaining why he wasn’t a Nazi.”

Sometimes, people bought it. Talley and Pace would get emails from people who were either horrified or totally on board with Buchanan’s fake positions. “They’d write, ‘I really agree with your message but maybe the swastika is going overboard a little bit,’” says Pace.

Some of the joke pages also ended up in Yahoo’s entirely serious list of presidential campaign sites, and overall, about 20 percent of the e-mails they received were from people who didn’t seem to get the joke. AOL provided a form for its members to send Clinton, Dole, and Newt Gingrich their thoughts about the 1995 budget negotiations, which were going badly; the form used an email from the Dole spoof site, and Talley and Pace started getting hundreds of presumably serious suggestions each day.

”There’s no shame in voting for a candidate who won’t win” (Image: Brooks Talley and Mark Pace)

”There’s no shame in voting for a candidate who won’t win” (Image: Brooks Talley and Mark Pace)

Most days, the sites got about 300 to 1,000 visitors, but once the media started covering them, tens of thousands of people were viewing Talley and Pace’s work. None of the campaigns, though, seemed too troubled by the bogus sites. “It is clear that it is a joke,” a Dole spokesman told the the Chicago Tribune. A White House spokesperson said that “parts of it were rather humorous.” (Possibly he hadn’t noticed that the red ribbon in one corner linked to cum.net.)

Just four years later, though, the political class had started taking the web seriously. The Bush campaign tried to stop anti-Bush postings at gwbush.com and bush.org by lodging a formal complaint to the Federal Election Commission. The campaign also pioneered a more web-savvy tactic: registering 260 Bush-related domain names so that they couldn’t be bought by anyone else.

An image from dole96.org (Image: Brooks Talley and Mark Pace)

Today, that’s become standard practice for politicians: in 2014, Michael Bloomberg bought hundreds of .nyc domain names that might otherwise be used for off-brand purposes. But it’s not a fool-proof strategy, as John Oliver proved, when he registered a bunch of his own Bloomberg-inspired sites, like tinytinybloomberg.nyc.

There are more basic forces at work protecting politicians from spoof websites: the amount of effort required to make a good one. If some prankster today wanted to make the 2016 version of Talley and Pace’s Buchanan site, it might mean spoofing Donald Trump’s website and replacing the current photo, in which he’s flashing the victory sign, with an almost identical picture in which he was flashing an offensive gesture, like a Nazi salute, or of clothing, such as a KKK hood.

At the very least, it’d require decent coding and photoshopping skills, and at that point, it’s simpler just to replace Republicans’ guns with giant dildos and post them on Twitter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook