The First Planned Parenthood Only Lasted For 10 Days But Started a Revolution

Mothers wait outside of America’s first birth control clinic. (Image: Library of Congress)

It’s been a particularly difficult week for Planned Parenthood, which has had to contend with a mass shooting at its Colorado Springs clinic, followed by the passing of a Senate bill that seeks to defund the entire organization.

The Senate vote is highly unlikely to have any legislative effects, but it sends a message that clinics like those operated by Planned Parenthood are a bitterly divisive presence in the United States.

This state of affairs, of course, is nothing new—it goes all the way back to 1916, when Margaret Sanger opened the nation’s first birth control clinic in a Brooklyn storefront. Her pioneering center lasted all of 10 days, but kickstarted a women’s rights revolution that continues to be fought today.

Born in 1879, Sanger (née Higgins) was the daughter of Irish immigrant parents, and grew up in upstate New York. She briefly attended Claverack College for nursing before marrying architect William Sanger in 1902. The couple had three children together and eventually moved to New York City, where Sanger became active in a number of socialist causes. While she was an official member of the New York Socialist Party’s Women’s Committee, Sanger really broke ground with a pair of sexually frank columns aimed at educating women about their bodies and their rights. Titled What Every Mother Should Know and What Every Girl Should Know, the columns discussed everything from sex, to the ways the human body changes during adolescence, to the science of birth—all subjects that were considered more than a little taboo at the time.

While working as a nurse in impoverished East Side hospitals, Sanger became acutely aware of the issue of reproductive rights, especially among the poor. She was faced with women who could not hope to support the number of children they had, women on whom the physical toll of repeated childbirth had left its mark, and, perhaps most tragically, women who had injured themselves in the process of DIY abortions. The problem as she saw it was not just a lack of access to proper contraceptives—Sanger was not an advocate of abortion, at least not at this stage in her career—but a lack of any knowledge about contraceptives at all.

This paucity of access and knowledge was in part due to the Comstock Laws, which regarded contraceptives and information about them as unlawfully obscene. Specifically, the law referred to sending such things through the U.S. Postal Service, but it also set a precedent that information about contraception was essentially porn.

Sanger sought to bring birth control into the mainstream conversation, going to increasingly bolder lengths to get people to stop treating reproductive rights like a dirty secret. She even coined the term “birth control” to replace the more delicate terms of the day such as “familial limitation.” In 1914, Sanger began sending out a series of short informational pamphlets called The Woman Rebel, looking to challenge the existing obscenity laws by testing them. Sure enough, seven of the nine issues of The Woman Rebel were, as Sanger described it in a later article, “suppressed,” and the Federal Grand Jury brought her up on charges, attempting to imprison her. Instead, she left the country for Europe.

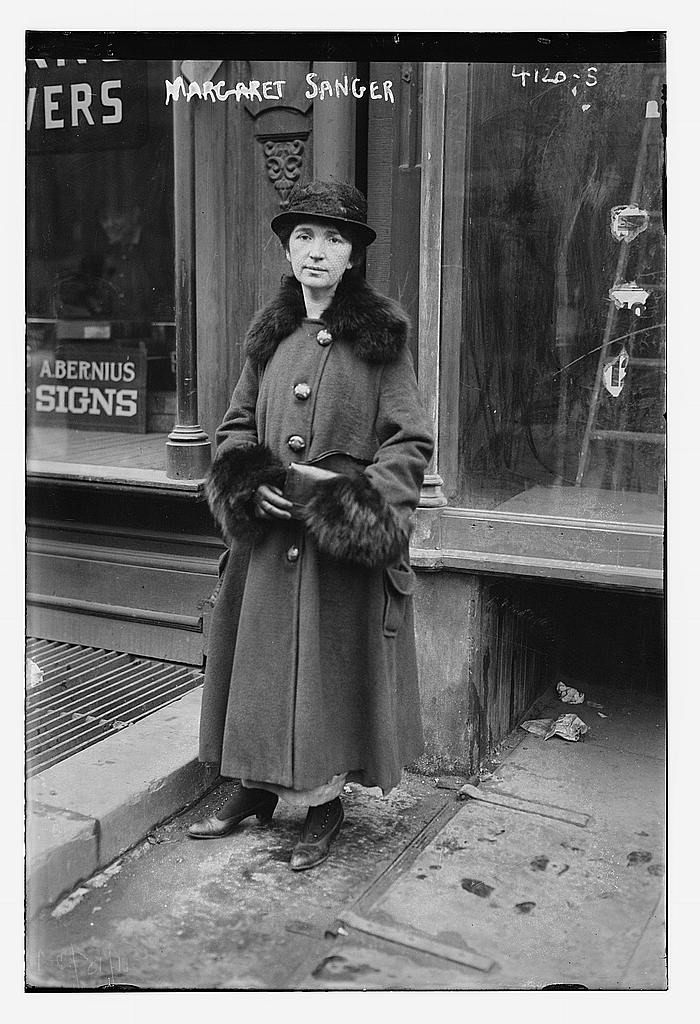

Margaret Sanger (Image: Library of Congress)

When she returned to the United States in 1916, Sanger was acquitted of her initial charges, but was more ready than ever to fly in the face of the government’s ridiculous laws and effect some real change. Thus she decided to open the country’s first birth control clinic.

During her time in Europe, Sanger had seen Norwegian birth control clinics that were able to help women gain access to contraceptives such as diaphragms, and wanted to start something similar in a location that would most benefit from the clinic’s services. Sanger chose the Brownsville neighborhood of Brooklyn for her clinic. At the time it was mainly inhabited by poor Jewish and Italian immigrant families, and in her autobiography Sanger herself described the area as “particularly dingy and squalid.” If it sounds like she wasn’t much of a fan of the place, the inhabitants of Brownsville seemed even less enthused about her setting up shop there. As Sanger recounts in her autobiography, she and her associates approached a number of local social organizations, all of whom wanted no part of her controversial scheme.

Finally, Sanger and her team were able to rent out a storefront at 46 Amboy Street for $50 a month, and the nation’s first birth control clinic was born. Consisting of just two rooms and a spot outside where mothers could leave their carriages, the tiny facility was perfect for their needs. The patients could wait in the outer room while consultations were held in the inner room. Though Sanger was not able to find a doctor willing to work at the clinic, an examination table was put in the back room, just in case they ever could find a willing physician.

Thousands of fliers were printed, calling for mothers who wanted to learn about contraceptives. “DO NOT KILL, DO NOT TAKE LIFE, BUT PREVENT,” the leaflets proclaimed. They were printed in English, Yiddish, and Italian, and were stuffed into as many mail slots and pedestrians’ hands as possible. Sanger was well aware of the legal trouble her new clinic could, and likely would, get her into. Far from operating in secret, she went so far as to mail a letter to the District Attorney of Brooklyn, letting him know that she would be distributing contraceptive information, and included the clinic’s address.

Having done everything she could to get the word out both to the women who needed to take advantage of the clinic and the lawmakers that needed to see it in action, Sanger and her associates opened the doors of their clinic on October 16, 1916. In her autobiography, Sanger said she didn’t know if anyone would show up, due to fear or disinterest, but she was relieved to find that when they opened the doors, there was already a line of some 150 people waiting to be treated. America’s first birth control clinic was in business.

Visitors would enter the private room alone, or in pairs, or sometimes even in large groups. Sanger would talk to them about contraceptives, what they were and how they worked. Mothers, daughters, young, old, wives, and even husbands, of all races and religions flocked to the clinic to receive advice. The clinic received so many visitors on its first day that they immediately had to begin telling people to return the next day.

Margaret Sanger and Fania Mindell inside the Brownsville clinic. (Image: Library of Congress)

In an ironic contrast to the perception that modern Planned Parenthood centers are simply “abortion clinics,” despite their inclusion of a wide range of women’s health services, Sanger’s original birth control clinic didn’t distribute contraceptives, yet many people came hoping to get an abortion. It was these women, many of whom would threaten suicide when they learned they could not receive an abortion, that Sanger wrote, “haunted [her] at night.” In her book she even described one woman who was so desperate not to give birth to a child that she threatened, “If you don’t help me, I’m going to chop up a glass and swallow it tonight.” If nothing else, Sanger had proved that there was an overwhelming need for her clinic.

The birth control clinic at 46 Amboy Street lasted for all of 10 days. As Sanger anticipated, it wasn’t long before the authorities cracked down on them. After sending in an undercover member of the vice squad (whom Sanger and her associates quickly spotted), the police raided the clinic on October 26, arresting Sanger. She was jailed overnight, but immediately attempted to reopen the clinic, although she was once again taken in by police.

Sanger would attempt to get the center up and running again a couple more times that November, but finally the police forced the landlord to evict her. In the scant 10 days that the clinic was open, it provided counseling services to nearly 500 people, taking case files on all of them.

After the demise of the Brownsville clinic, Sanger turned her efforts towards more formalized approaches to advocating reproductive rights, founding the American Birth Control League, and later on helping to found Planned Parenthood. She devoted her entire life to the betterment of women’s rights and eliminating the barriers to access to birth control, and sparked a national revolution with that two-room store front.

The original building at 46 Amboy Street was demolished, but a new building now stands on the spot, boarded up and, when last captured by Google Street View, lined with discarded mattresses. The site of Sanger’s clinic is not protected by any landmark status, and bears no sign of its historic past.

46 Amboy today. (Image: Google Maps)

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook