The Folsom Prisoner Who Built Functional Miniature Carnivals Out of Toothpicks

It was the best way for William Jennings-Bryan Burke to kill time during his 23 years in prison.

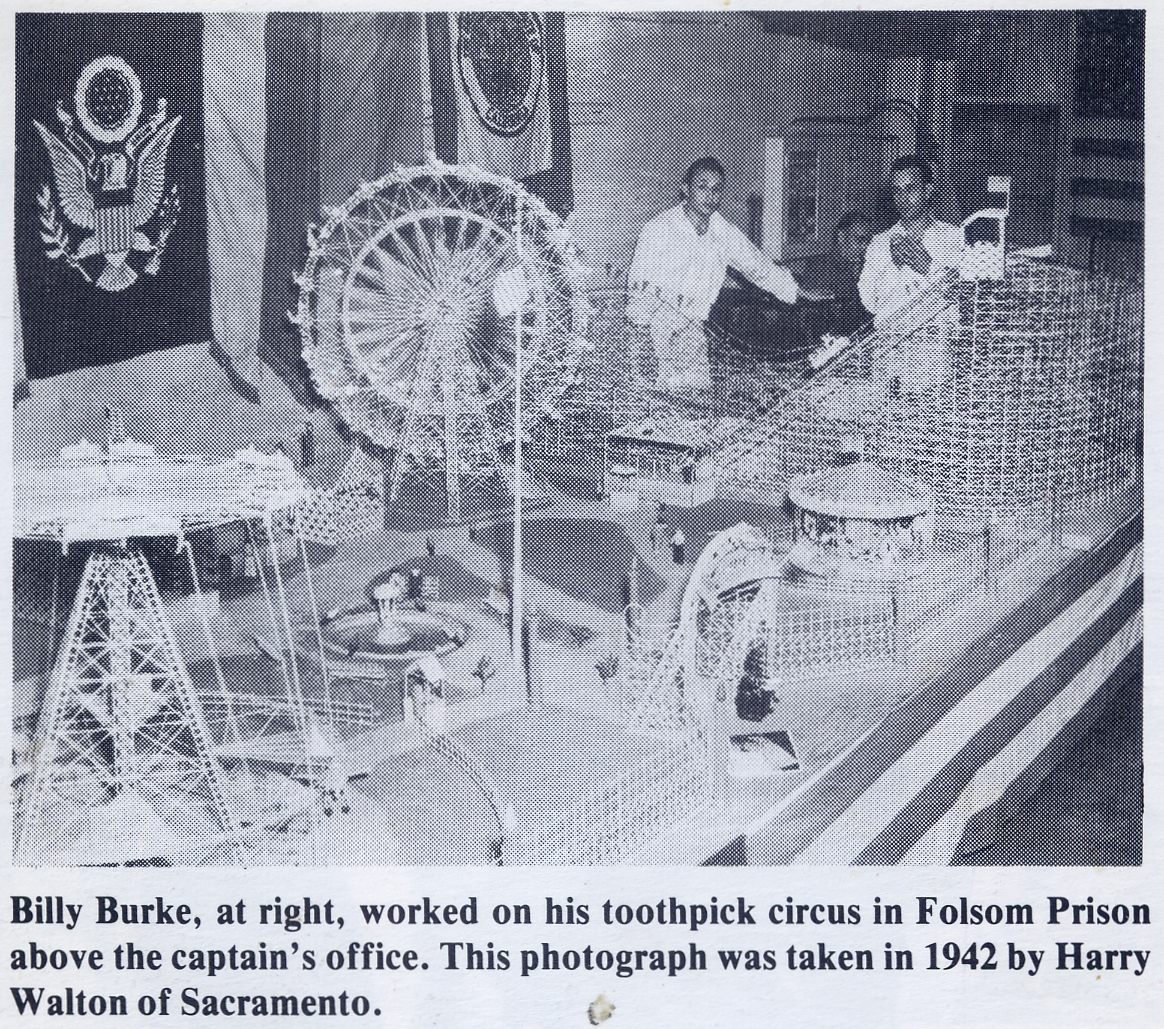

Former convict Billy Burke had a unique hobby during his time at Folsom Prison. [All photos: John Burke/The Toothpick Carnival]

For his last 16 years as an inmate at Folsom State Prison, near Sacramento, California, William Jennings-Bryan Burke (better known as Billy Burke) spent his time fiddling with hundreds of thousands of toothpicks.

Sometime around 1940, the convicted burglar turned a basement near the warden’s office into his artistic domain. Relying on his memories and imagination, he constructed three expansive carnivals containing scaled iterations of Ferris wheels, roller-coasters, air plane rides, merry-go-rounds, and penny arcades—all made out of toothpicks.

Burke got to experiment with his toothpick creations in the basement of Folsom Prison. [Photo: John Burke]

“For a time toothpicks had been designated contraband in prison, precisely because I was using so many of them and the guards weren’t sure of what I had in mind,” Burke told Nan Nichols Sharrer, author of Escape From Folsom Prison: The True Story of William Jennings Bryan Burke. “But soon the warden would bring me toothpicks in his pockets.”

With just a carving knife and glue, Burke would painstakingly piece together the thin splintered pieces of wood by hand into beautiful fully-operational rides and attractions. He even carved out miniature carnival attendees and placed them in life-like situations throughout the park.

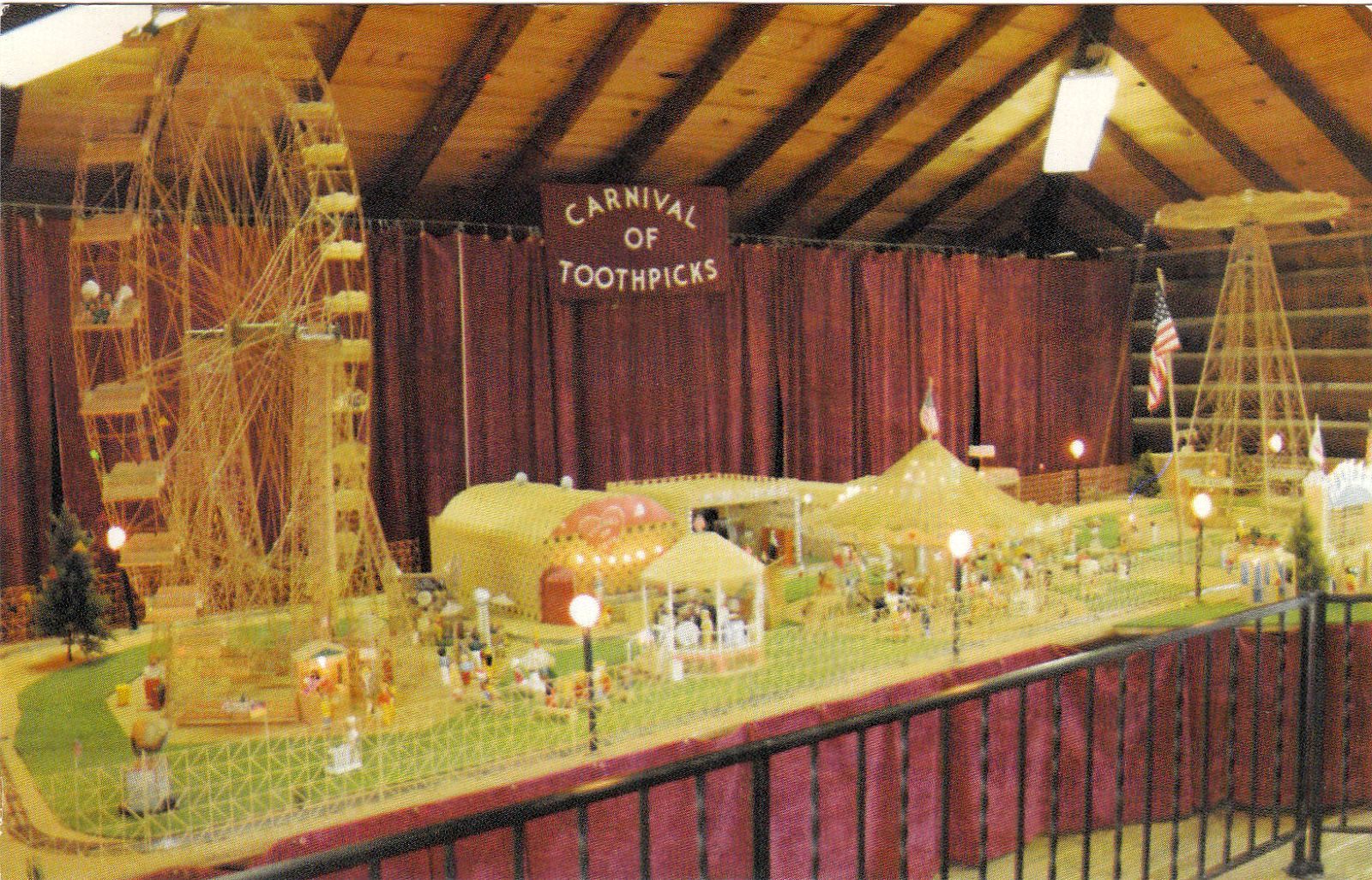

This late 1970s carnival is one of Burke’s most colorful and realistic.

This late 1970s carnival is one of Burke’s most colorful and realistic.Burke spent 23 years at Folsom Prison, between 1928 and 1956, from just before his 19th birthday until he turned 47. A full five of those years behind bars were dedicated to constructing the first of his elaborate toothpick carnivals, which he modeled after beachside amusement parks he visited as a child.

“He was very good with his hands,” says John Burke, one of Burke’s sons. While Burke was well-known for being crafty, it wasn’t usually for the artistry of his toothpick fantasies.

Burke built multiple carnivals named “Playland” both during and after prison. The pieces featured here were during his time at Folsom. Burke, 5’6” tall, stands just a bit taller than the Ferris wheel on his right.

Born in 1909, Burke grew up in Lake Elsinore, a resort town in southern California. He started getting into trouble in his teenage years, running away from reform schools and becoming involved in petty theft, snatching coin-boxes from buses and cracking safes in businesses. In 1928, transgressions such as these landed Burke in Folsom Prison.

Burke was restless in prison, and made several failed plans to escape, including digging holes and tunnels. His most complicated scheme saw him building a hot air balloon that used the gas in the sewer department of the prison to run.

This mini-toothpick carnival, called “Toothpick Fantasy,” operates at Musée Mécanique in San Francisco.

This mini-toothpick carnival, called “Toothpick Fantasy,” operates at Musée Mécanique in San Francisco.

But in 1929, one of his attempts actually worked. Burke built a dummy and placed it in his bunk before sneaking into the prison morgue, where he concealed himself in a coffin. Under cover of night, he crawled across the prison yard, past guard towers, and into the surrounding canal.

Burke’s creative escape was featured in the 2002 History Channel documentary The Big House. “He was one of the few people interviewed on this TV show that successfully escaped from Folsom,” says John Burke. “But, the only thing that really bummed me out was that they didn’t talk about the toothpick carnival.”

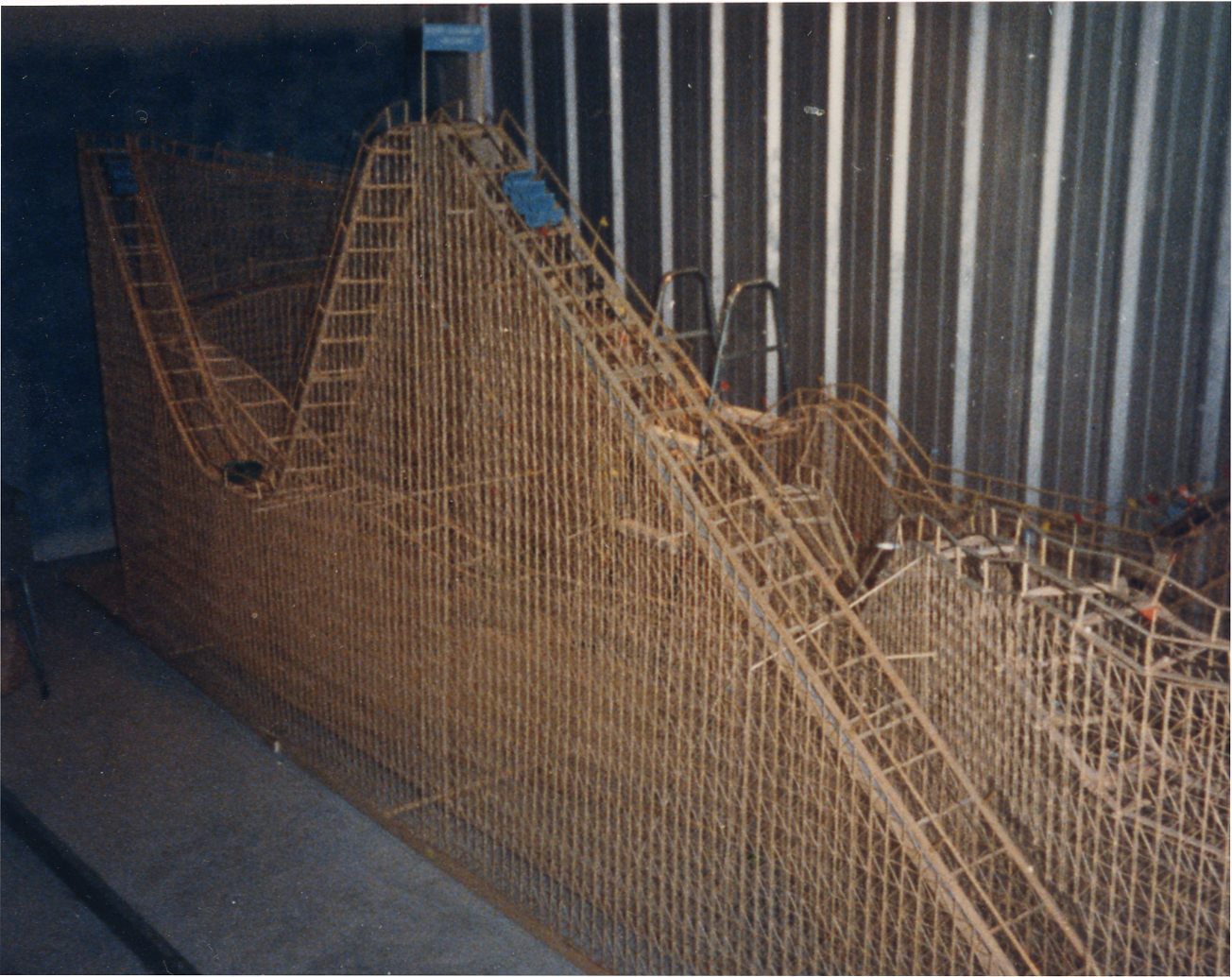

A five-foot tall roller-coaster that Burke built at a storage facility that he worked at after prison.

After his escape, Burke made it to Philadelphia, but quickly fell into his old thieving ways. He was sent back to Folsom just two months after his daring break-out. As punishment, Burke had to spend six months in solitary confinement—trapped in total darkness with only a waste bucket and a door slot for food.

Burke reflects on his time in solitary in Escape From Folsom Prison:

“It is unlikely anybody can imagine what it was like in solitary confinement in 1929. The system has changed today. Now they give prisoners a light in their cell and a few things to read. Some writing material perhaps. They’ve made a great deal of changes, but in the early 1930s when a man went into the hole, they treated him more like an animal than a man.”

All of Burke’s subsequent escape attempts were punished similarly.

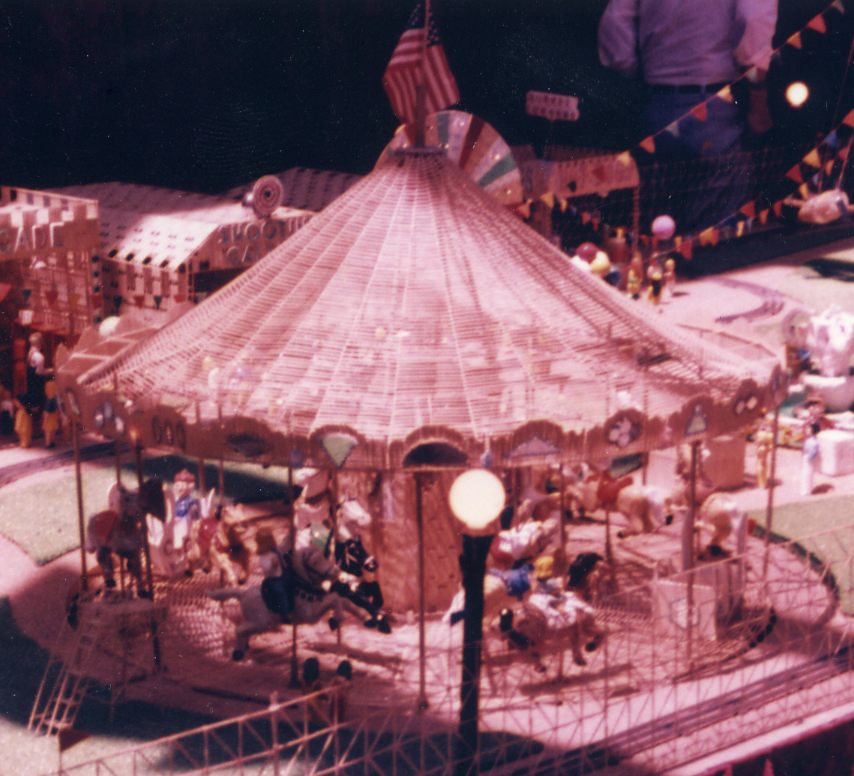

Burke would also paint the structures, like this 1970s merry-go-round, by hand.

Burke would also paint the structures, like this 1970s merry-go-round, by hand.After several turns in solitary confinement, Burke decided to settle down and follow the rules. The other convicts and the guards treated him like a kid. His antics “brightened up the joint” and “some of the [convicts] would smile at my tricks,” he said.

Around 1940, his creativity began to blossom. He had taken a hobby class that allowed him to carry a small knife for carving wood. To busy himself, he started carving boats out of wood, and then fashioning roller-coasters. He even built an airplane with a five-foot wingspan out of wood and canvas.

One of Burke’s most impressive pieces is an eight-foot Ferris wheel that seats 32 miniature carved carnival attendees. Gleaming under lights, this delicate double-wheeled toothpick creation looks like it’s made out of glass or crystal. It currently resides at Folsom Prison Museum.

One of Burke’s most impressive pieces is an eight-foot Ferris wheel that seats 32 miniature carved carnival attendees. Gleaming under lights, this delicate double-wheeled toothpick creation looks like it’s made out of glass or crystal. It currently resides at Folsom Prison Museum. While building planes, Burke got a hold of a special tube of glue that had a picture of the Eiffel Tower made out of toothpicks. That’s when the idea hit. “I let my imagination go to work,” Burke recalled in Escape From Folsom Prison. “I drew a big circle on a sheet of plywood and started to work on my first toothpick Ferris wheel.”

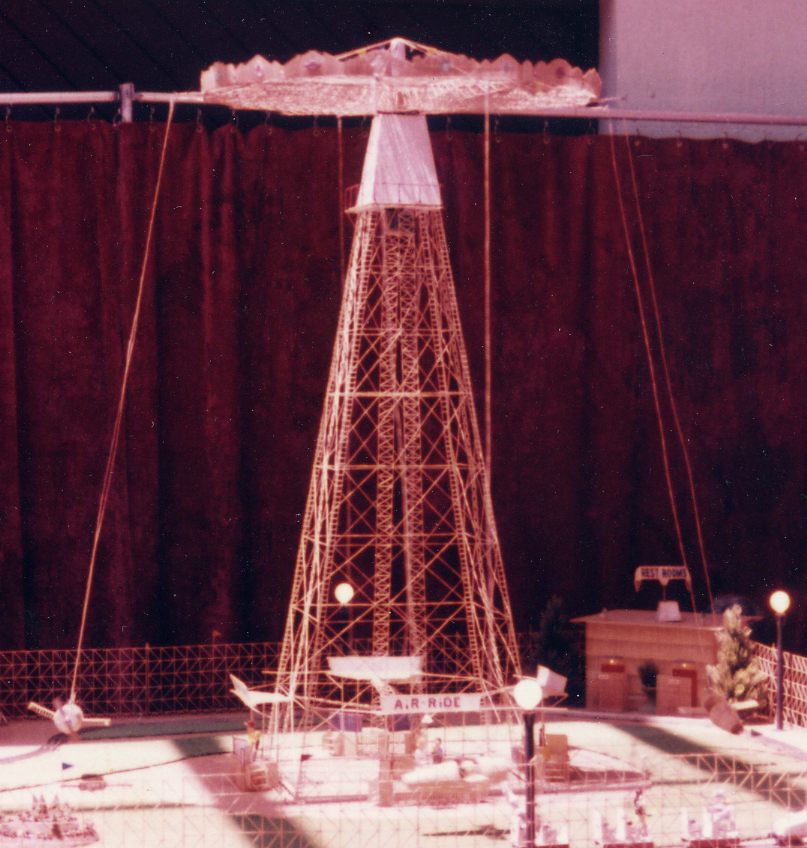

He added more pieces to the carnival: a roller-coaster, concession stands, restrooms, fountains, a bandstand. Almost everything was made out of toothpicks—even the cables that suspended the swinging airplanes on the air ride were made out of toothpicks that had been glued together. To make the rides operational, he took motors from small gadgets and incorporated them into the wooden structures.

Another Playland carnival built around the 1970s. Burke traveled with his carnivals after prison, showcasing them at different fairs and amusement parks.

Another Playland carnival built around the 1970s. Burke traveled with his carnivals after prison, showcasing them at different fairs and amusement parks.Recognizing his talent, warden Clyde Plummer instructed guards to leave Burke alone while he built his creations, and even gave him access to a large basement in the prison. Plummer revised the public visitation rules for Folsom Prison, which had been seen as an odd, isolated place. Soon, the warden was bringing large groups of weekly visitors, sometimes as many as 300 people, to the prison to see Burke’s toothpick Playland, and encouraging them to pay for the privilege. He let Burke keep the money.

Burke was unique in the prison system, but he was not an anomaly. “There were men of many talents in Folsom Prison: Artists, painters, mechanics, poets,” Burke said in Escape From Folsom Prison. “Of course, they had a lot of time to perfect their skills.”

This air plane ride stands over five feet tall. It was built in the 1970s.

This air plane ride stands over five feet tall. It was built in the 1970s.In 1956, Burke was released from prison. He married, had four children, and found work in janitorial, maintenance, and storage companies. All the while, he continued building toothpick carnivals that were even larger than the one in Folsom.

Burke showcased them at fairs and amusement parks, but refused to charge a separate admission fee to see them. He often needed to sell the toothpick carnivals to pay his fare back home, where he’d have to build new ones. At the Solano County fair, he showcased a massive 24-foot carnival made with 250,000 toothpicks.

“He once was building something inside his house and he ran out of space so he knocked out the counter,” says John Burke.

Burke died in 2001, at the age of 92, but his toothpick legacy continues to tantalize visitors. Operational carnivals are on exhibit at the Folsom Prison Museum and Musée Mécanique at Fisherman’s Wharf in San Francisco.

“He always carried a tube of glue and a knife with him,” says John Burke. “He was always working on something.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook