The Freakiest TV Hack of the 1980s: Max Headroom

Max Headroom himself. (Photo: Ingrid Richter/Flickr)

Hacker. According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, the word means “a person who secretly gains access to a computer system in order to get information, or cause damage.”

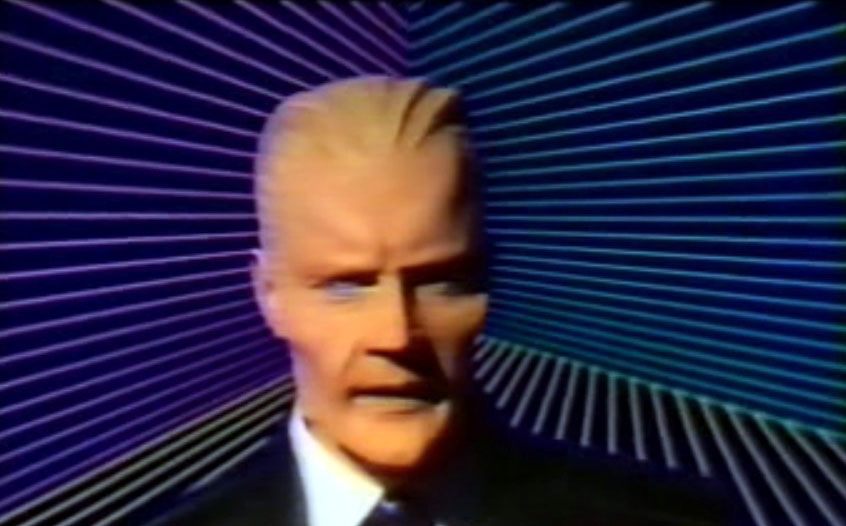

But 28 short years ago, the term hardly existed–that is, until the Max Headroom Incident. At 9:14PM on November 22, 1987, the regularly scheduled programming at WGN Chicago, a local news station in Illinois, was interrupted. The screen hissed and burped, materializing into a figure with a pallid mask bouncing around in front of a corrugated metal background.

Before the mysterious intruder could speak, however, the WGN technicians switched the signal and returned to the local news.

The first attempt at the hack. No audio made it to broadcast.

Two hours later, at approximately 11:15PM, a scheduled broadcast of Dr. Who on Chicago-area PBS affiliate WTTW-11 was broken off. The same masked figure appeared as it had two hours before. Except this time, there was audio. For over a minute and twenty seconds, unsuspecting Chicagoans were subjected to the strange cackling and unintelligible rambling of the masked individual. He also exposed his bare buttocks, which a mysterious woman began to smack with a fly-swatter.

The first successful “hack” of a television station quickly garnered a lot of attention, kicking off a federal search for the culprits. Nearly three decades later, they still have not been found.

The second, successful hack with audio.The mask worn in the video was seemingly a crude representation of the titular character in the science fiction series, Max Headroom. In the show, a computer-generated television journalist–Max Headroom–reports the news from a dystopian future, where large media corporations dominate society. The corrugated metal slab in the background of the signal intrusion was an attempt at recreating Max Headroom’s retro-futuristic broadcast background.

In 2010, Reddit user “bpoag” volunteered some information in an Ask Me Anything thread, where he put forth a theory about the unsolved television intrusion of 1987. Hailing from the suburbs of Chicago, bpoag was an avid “phreaker” as a teenager in the late 1980s. Phreaking, according to bpoag, is “the art and science of manipulating telephone networks and the systems which live on them.”

In other words, it’s a precursor to the computer hacking we know today.

Max Headroom was ubiquitous in the late 1980s. Here he is as a spokesman for New Coke.

Bpoag (who asked Atlas Obscura to withhold his real name) was peripherally involved with a group of phreakers operating in LaGrange, a suburb of Chicago. The de-facto leaders of the group were two brothers in their early 30s, called “J” and “K” (bpoag also asked to protect their identities).

In 1987, the week before the infamous hack, the brothers warned bpoag, who was 13 at the time, that they were planning to do something “big” over the weekend. Later, they told him to tune into channel 11 on the evening of November 22nd.

According to bpoag, the actual “hack” was simple enough to pull off, and didn’t require any advanced or technical equipment beyond what an avid phreaker would already have had in his arsenal. He writes, “All that had to be done, apparently, was to provide a signal to the dish that was of a greater power than the legitimate one.”

The older brother, “J,” had “moderate to severe autism,” says bpoag, but was a capable phreaker. The ramblings heard in the intrusion, including threats to Chuck Swirsky (a popular Chicago-area sportscaster), and a hummed version of the “Clutch Cargo” theme song, seemed to reflect J’s interests at the time. This is the crux of bpoag’s argument.

When asked about the motivations for the hack, bpoag likened it to a kind of public service announcement. “It only lasted as long as it needed to get the point across: that point being that the airwaves were woefully unprotected, and easily exploitable. It’s the equivalent of having your picture taken on the summit of Mt. Everest before coming back down.”

But this was 1987–a few years before the advent of the World Wide Web, and long before the concepts of trolling and hacking became known. The audiences subjected to the Max Headroom intrusion were deeply perturbed by what they saw. “I got so upset that I wanted to bust the TV set,” one man told a reporter for WGN, one of the affected TV stations.

Though the true identity of the hackers, and their motivations, are lost in time, the legacy of the Max Headroom Incident endures. Informed by the original signal intrusion on that fateful November evening, hacking has moved from the realm of merry pranksters to serious protest, and even government-sponsored terrorism, over the past 30-odd years. The Max Headroom hackers, who were likely just trying to have a bit of fun, predicted a global movement.

The high profile Anonymous group uses the Max Headroom motif in their videos, seen here in a 2010 warning to the Church of Scientology.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook