The Friday Night Rites of New York’s Church Bell Ringers

What is about to happen here? (Photo: Ella Morton)

It’s a frosty Friday evening in New York and, as most people are fleeing Wall Street to head home, Tony Furnivall is just arriving. At the end of the street, built into the stone wall surrounding Trinity Church, is a heavy door with a big cross on it.

He swipes an access card, clambers through the bowels of the church, and then begins the climb up the clock tower. There, in a dimly lit room that overlooks Alexander Hamilton’s grave, he’ll find a circle of ropes dangling from the ceiling.

This sounds like the beginnings of some dark Masonic ritual, but it is nothing of the sort. Furnivall is a bell ringer and he’s here for this week’s practice session. Soon he’ll be joined by seven other bell ringers, all of whom will climb up to the clock tower to pull the ropes attached to bronze bells that weigh hundreds of pounds.

Tony Furnivall beside one of the dozen bells in Trinity Church’s clocktower. (Photo: Ella Morton)

Bell ringing, also known as change ringing, is what Furnivall calls “an ultra-niche interest.” Originating in medieval England, it is practiced by an estimated 40,000 people around the world today, mostly in the United Kingdom and among countries of the former British Empire.

In the U.S., there is a small but enthusiastic bell-ringing scene, spread across 42 towers. The North American Guild of Change Ringers, established in the 1970s, calls ringing ”a team sport, a highly coordinated musical performance, an antique art, and a demanding exercise.”

The initial attraction of the pastime, says Furnivall, is about ”controlling several hundred pounds of metal using only a rope, and making the loudest known noise of a musical instrument.” After that novelty wears off, it’s all about honing the teamwork and precision that, together, can result in perfectly choreographed musical moments.

Trinity Church. The bell ringing happens in a room behind the clock face. (Photo: Gryffindor/Wikipedia)

Ringers sound the bells for practical purposes—Sunday church services, weddings, special occasions such as ticker tape parades—but also just for fun. At Trinity Church on Wall Street, there are about 30 volunteer bell ringers on the books, eight to 20 of whom will turn up for practice on Wednesday nights. (This Friday session was an anomaly, organized after the church needed to do a recording session on Wednesday.)

Shortly after Furnivall arrives, he is joined by the other regulars, who hang up their coats, chat for a bit, then each grab a rope so the session can start. Eavesdropping on their conversations, one thing becomes immediately apparent: there are a lot of Brits in this belfry.

Furnivall estimates that around half of the regulars are expats. Some have grown up in bell-ringing families, while others encountered the activity through the church—not that you need to be a member of the congregation to be a bell ringer. ”Church involvement is pretty well irrelevant,” says Furnivall. “We enjoy ringing their bells, and they enjoy having their bells rung.”

Heavy-duty soundproofing in the bell tower means that their two-and-a-half-hour practice sessions don’t disturb the neighbors.

The practice session begins with rounds, which are like scales on a piano. The ringers stand in a circle, each holding a rope, and watch one another carefully. The person ringing the lightest bell pulls his or her rope first, while announcing, “Treble’s going!” Half a second later, a shout of “She’s gone!” makes it clear that the bell has started swinging and the round has begun.

Because there is a gap between pulling on the rope and the bell clanging, ringers must pay close attention to one another’s movements in order to get the timing right. With up to 12 bells in the mix, this can be very challenging.

This evening’s practice benefits everyone, but is particularly helpful for David Henry, the rookie of the group. He is only on his fourth year of ringing—the rest have been at it for at least eight or nine years. Clad in a cycling jersey and jeans, Henry spends the session holding various ropes, occasionally receiving over-the-shoulder coaching from one of the veteran ringers.

It is only toward the end of the night, when asked how he got into all this, that Henry mentions the fact he used to be a Benedictine monk. He says this as casually as someone else might note, “it’s chilly in here.”

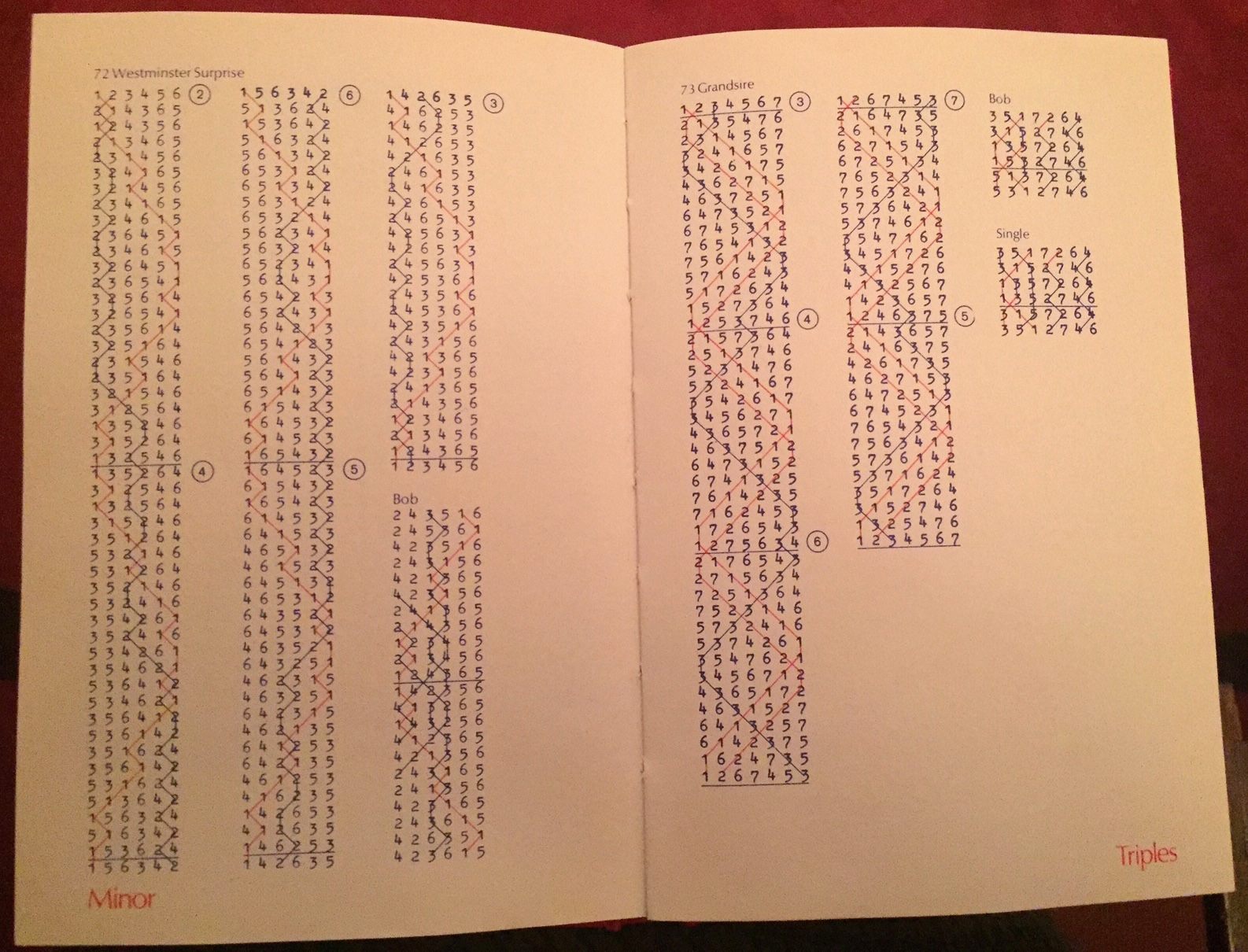

A book of “methods” shows bell ringers when to pull their ropes. (Photo: Ella Morton)

Henry is not the only ringer with an intriguing background. Trinity’s bell ringing squad includes “bankers, accountants, consultants, court reporters, lab directors, teenagers and retirees,” says Furnivall. Two of tonight’s participants, a couple, are doing PhDs in mathematics. They met through bell ringing.

It attracts a wide range of people, but the common personality traits, according to Furnivall, are introversion and an interest in patterns. ”Your geek quotient has to be very high,” he says. “If you live in the interior world” he says, pointing to his head, bell ringing is “unbelievably sexy.”

“If you enjoy the old Busby Berkeley musicals from the late ’20s and ’30s and the kaleidoscopic patterns that he creates, the chances are good that you would find bell-ringing attractive,” Furnivall adds.

Trinity Church’s tranquil yard is visible from the bell tower. (Photo: Ingfbruno/Wikipedia)

The references to retirees and old Hollywood musicals bring up an issue that’s affecting bell ringing worldwide—how to bring younger people into the fold. Bell ringing can be done by anyone, regardless of age, sex, or religious affiliation, yet is often marketed as a traditional art with medieval church origins.

This framing, it turns out, is not terribly appealing for the teens of today. Furthermore, ”I think Quasimodo gave us all a bad name,” says Henry.

Furnivall’s approach to this is a simple reframing: rather than presenting bell ringing as a centuries-old, church-focused tradition, he emphasizes the joy behind the music. “We ring bells to celebrate,” he says, and if you’re spry enough to clamber up a clock tower, you can grab a rope and join in the fun.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook