The Hidden World of Tenement Fortune Tellers in 19th Century Manhattan

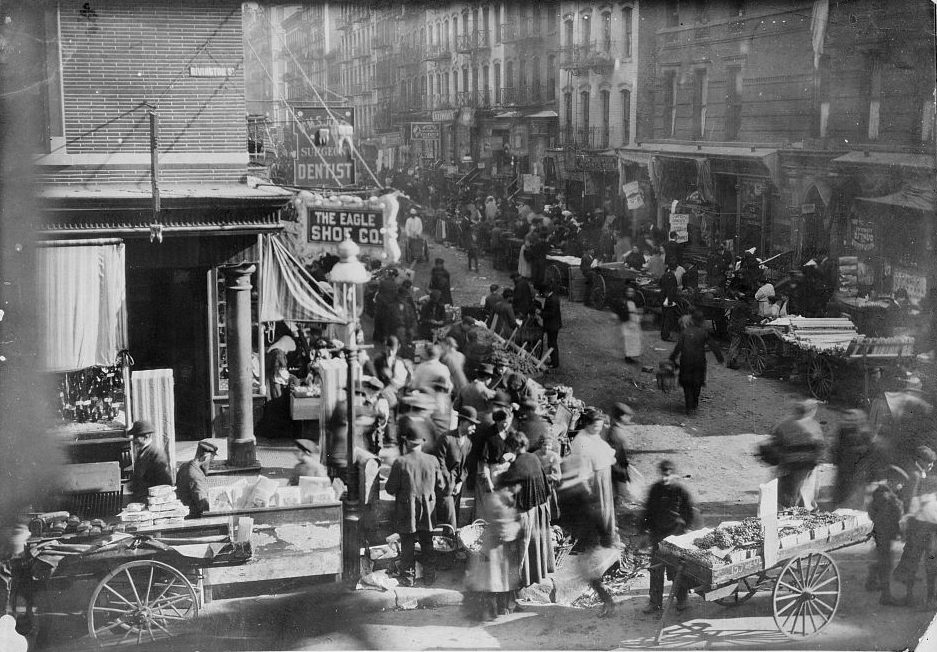

A crowded street scene on the Lower East Side, 1909. (Photo: Library of Congress)

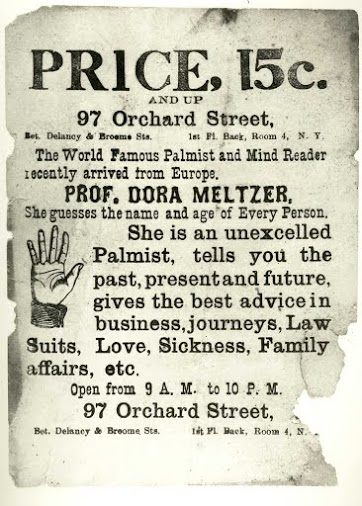

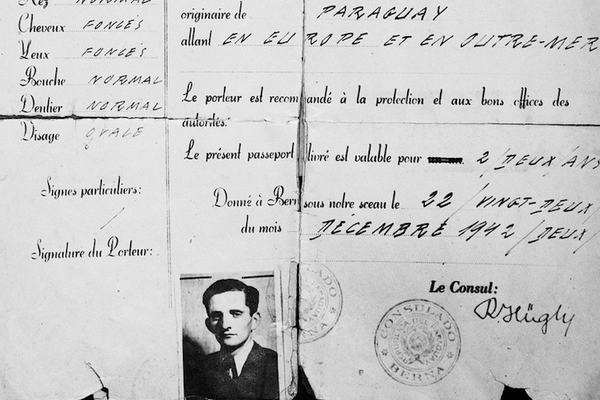

In 1993, a restoration was underway at 97 Orchard Street in New York City. Beneath the darkened floorboards of one apartment, left unchanged for 50 years, a thin, frayed piece of paper from the 19th century was discovered; with one side printed in English and the other Yiddish, it advertised the fortune-telling specialties of “The World Famous Palmist and Mind Reader”, Professor Dora Meltzer.

The people who found this paper worked at the Tenement Museum, founded in 1988 to teach the history of immigrant life in New York through old tenement apartments in Manhattan. At the time, the Orchard Street building had recently been acquired, and the museum was renovating the apartment to use as a historical teaching tool. Layers of wallpaper were peeled back, and items from the 1800s through the 1930s were found in the apartments during the process, but this particular paper was a contextual mystery.

Who was Dora? What fortunes did she tell her guests, and where did she end up? This sparked an ongoing search for who she was and what her business meant to the Lower East Side’s Jewish neighborhood in the late 19th century.

Dora Meltzer’s fortune telling business card: a flyer that advertised her mind-reading abilities. (Photo: Courtesy the Tenement Museum)

Fortune-telling as a pastime and as a business can be found in a majority of cultures in the world. In New York’s early Jewish immigrant communities, fortune-telling often came with a notion of exoticism, mixing Jewish mysticism with a foreign, sage-like edge. Many Jewish fortune tellers, like Dora Meltzer, used imagery that alluded to a hebrew palm-reading manual dating to the 1500s called Khokhmes Hayad (The Wisdom of The Hand), or drew from the old-world appeal of Eastern Europe, where the practice was likely common in villages.

In Europe, some fortune tellers traveled for profit, including Lyla Terfin, who donned a turban and an elaborate backstory of her powers tracing back to India, but was actually a Jewish woman named Elsa Frankel, from Minsk. Others, like the poet and bohemian Naphtali Imber, toured the United States. Most famous for writing the Israeli national anthem “Hatikvah”, Imber made public predictions as “Mahatma”, some of which creepily came true (that Californian wines would gain esteem, that the sun’s rays could be harnessed for power) and others that fell a little flat over time (that Kansas would take part in a new civil war between the Eastern and Western parts of the United States).

For stay-at-home fortune tellers like Dora Meltzer, using details like the title “professor,” and that she “recently arrived from Europe” were enough, and lent her traditional roots and current standards of legitimacy in two fleeting sentences. For 15 cents, her clients could learn when they’d fall in love, when to start their own businesses, or Dora could even guess, as it says in the Yiddish version of her flyer, “how much money is in your pocket.”

The prevalence of fortune-telling was especially relevant as a social and cultural hallmark of immigrants in Dora’s time. New York tenement life was not easy, and opportunities for immigrant workers, who often faced language barriers along with social stigmas from old American xenophobia, did what they could to survive in their new home. With scant support from former networks in their native countries, immigrants sought emotional well-being along with financial security, in whichever ways were available to them at the time.

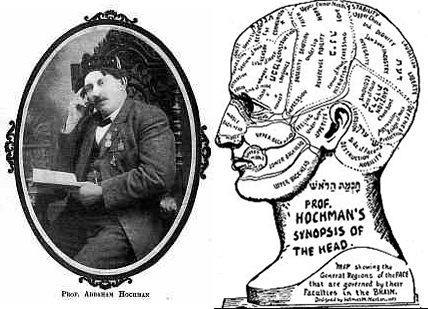

A photograph of Abraham Hochman and his ‘synopsis of the head’, from his book The Key to Prophecy. (Photo: Courtesy Jane Peppler/Yiddish Penny Songs)

“What appeals to me most [about Dora Meltzer’s flyer], is that it’s an entrée into a larger dynamic on the Lower East Side, which was new immigrants that needed advice, and who were the people who could guide new immigrants as they adjusted to America,” says Dr. Annie Polland of the Tenement Museum. “Often those people were found within the community–immigrants that maybe had come five years before.”

Working from home as customers filed in throughout the day, wives and mothers were able to meet new people and function almost as therapists, in a pre-talk therapy time. Lawrence J. Epstein writes in At the Edge of a Dream that housewives could also “raise some funds, be relieved of the tenement’s isolation, and develop social relationships with others.”

Fortune-tellers of Dora’s era often promised to help with immediate family concerns, namely, the very common issue of immigrant fathers and husbands leaving their families. This was a problem of every immigrant community of the time, but was well-documented in the Jewish community, thanks to a fastidious and beloved newspaper culture among the Yiddish-speaking population. Ehud Manor recounts in his book, Forward, that in 1909 the Jewish Daily Forward estimated that 31,000 men left their families. This prompted a “Gallery of Deserting Husbands” column in the paper about who had left their homes, their description, and a call to bring the deserters home to justice.

The busy corner of Rivington Street and Orchard Street, 1915. (Photo: Library of Congress)

This was, at the time, considered an epidemic and social crisis. Men would leave families behind in Europe and start new lives in the U.S., but could also easily leave their city, region, or even their neighborhood and easily claim new identities, shirking their responsibilities to their wives and children, who were dependent on their support. For many women, a desperate recourse was to go to the nearest fortune teller and hope for the best.

Abraham Hochman was one such fortune teller in the Lower East Side of the time. One of Hochman’s specialties was locating missing husbands. “Hochman is listed everywhere…he’s even in the census as a clairvoyant,” says Dr. Edward Portnoy, historian and Yiddishist at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. At a recent Tenement Museum talk, Portnoy recounted how in one story, a woman paid the hefty price of one dollar (versus 15 cents) to visit Hochman in order to retrieve her deserting husband. She was told she would find him on a particular street corner at 10 p.m. When she later brought a police officer to the specified location, they found her husband scratching his back on a lamp post–he was likely arrested before being made to pay alimony as reparation.

However, this is not to say that women were the only patrons of fortune tellers: Hochman notably predicted a winning horse in a race for politician Timothy Sullivan, a win that Portnoy notes made Hochman the official psychic of Tammany Hall’s Lower East Side branch. It’s possible that fortune tellers, with their broad connections and constant stream of local stories actually did have a solid insight into what was most likely to happen in the local future.

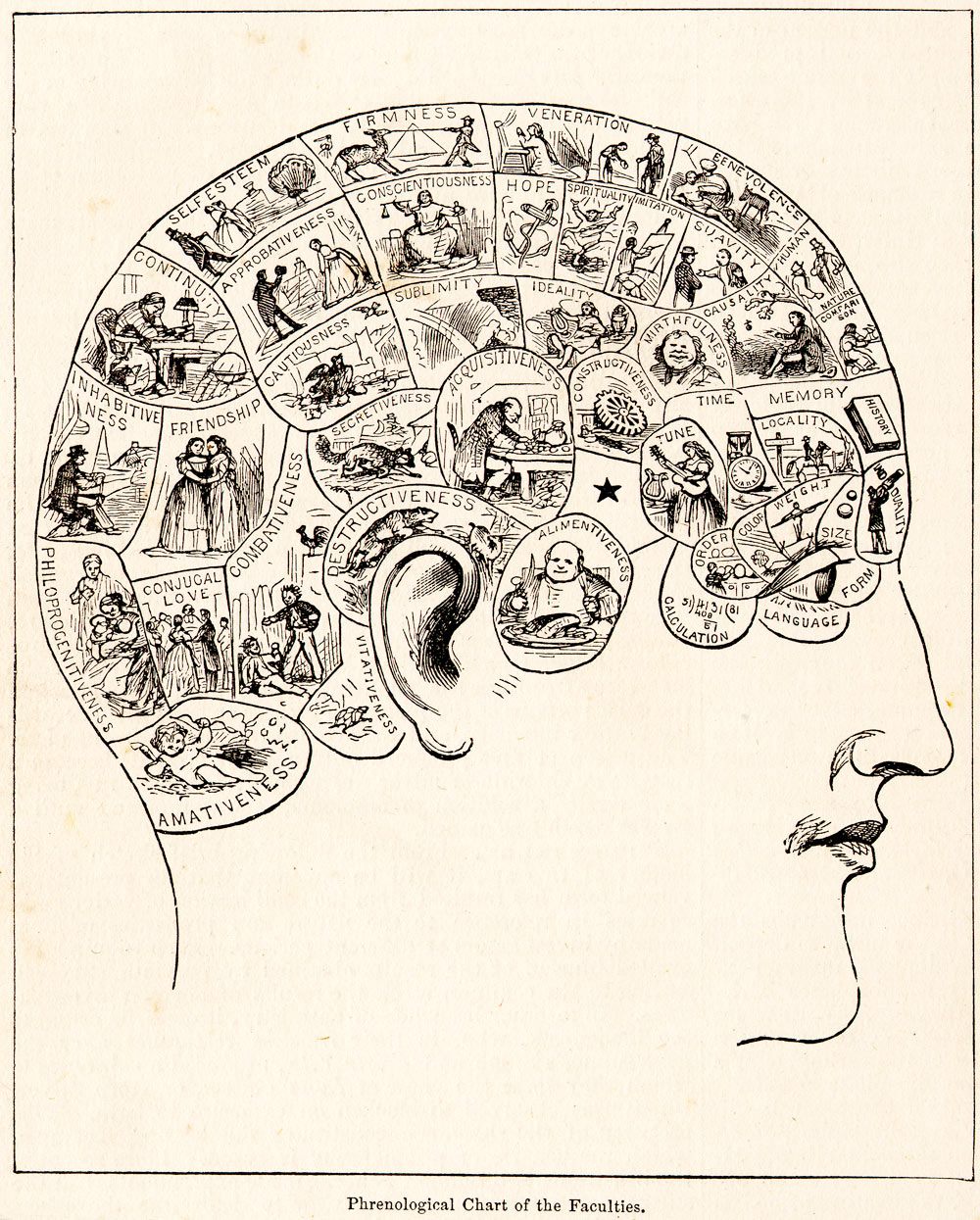

An 1883 phrenology chart. Phrenology was one type of practice used by fortunte teller Abraham Hochman. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Hochman was, to Portnoy’s estimation, one of the most famous Jewish fortune tellers of the day. He was so bold with his business that he wrote his occupation as ‘mind reader’ in the 1910 census, and according to Portnoy’s research was known as “the richest man on Rivington Street”. His success flowed into other businesses, including hotel keeping and even selling his own Passover Haggadah, complete with advertisements for his occult services.

He even released a book called The Key To Prophecy which purports to share his mystic methods, including an ‘astro-biblical chart’ that helped clients answer questions like “should I take dance lessons?” and “is my landlord in love with me?”. Hochman became beloved of the community, which he gave back to with lavish block parties. Hochman advertised a variety of occult practices, from phrenology, the pseudoscience of studying head shapes, to divine personality traits, to palm-reading and astrology, all of which became illegal in New York City in 1911.

Over the years, suspicion of immigrant practices like fortune-telling was equated with fraud and common swindling. A 1909 New York Times article estimated that $10,000 a day was paid to some 1,000 fortune tellers of all cultures at a time when a simple reading typically cost 15 cents, and cautioned that, “the opportunities of the unprincipled person to prey on the ignorance and pathetic truthfulness of these believers in the occult is almost limitless.”

The notion that fortune tellers swindle their customers remains to this day. The crime of fortune-telling changed from being a disturbance of the peace to a Class B Misdemeanor in 1967. The New York law states that except for explicit entertainment-only purposes, “a person is guilty of fortune-telling when, for a fee or compensation which he directly or indirectly solicits or receives, he claims or pretends to tell fortunes,” among other supernatural claims.

A present-day fortune teller in New York’s East Village. (Photo: Mike Licht/flickr)

A best-selling tax book, J.K. Lasser’s Your Income Tax 2012, even explains tax write-offs for victims of fortune teller fraud, which is grouped into “theft loss” alongside riot losses, foreign government confiscations, and being swindled by friends. Today, as in the past, fortune tellers are both reviled and loved for their services, exoticism, and claimed powers; with private detectives and public outcry competing with the loyalty of the fortune tellers’ customer base.

In contrast to the bountiful accusations of fraud and immoral behavior by fortune tellers that came in the next century, Dora Meltzer was likely a housewife earning some small-time income on the side while connecting to her peers. Her business card is a unique document showing Jewish women advertising their clairvoyant talents, as opposed to men like Hochman, and may shed even more light on the lives of tenement families. Maybe more striking, though, is how a piece of paper that was generally considered undesirable became so curious and important to investigate. Dora’s flyer, for all we know, could be one of many similar advertisements that were disregarded as objects, rather than saved.

“It’s weird, it’s actually amazingly lucky that they found that, because it was probably a relatively common thing, and it was a thing that nobody bothered to save,” says Portnoy. “It’s like the stuff people give you on the subway–no one keeps that, you just throw it away. You never think this stuff has historical value.”

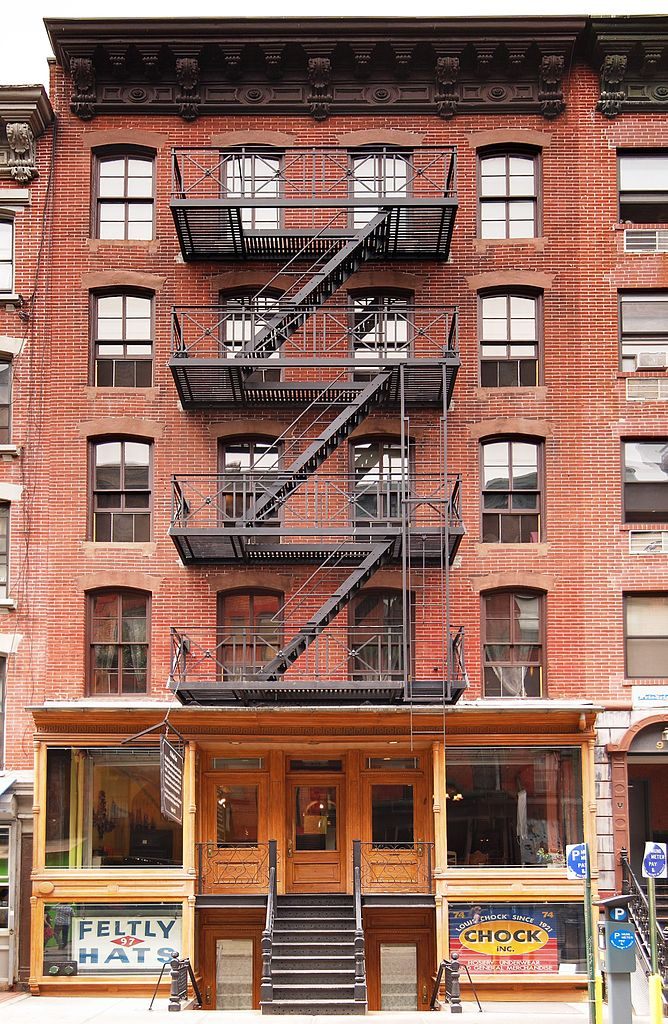

97 Orchard Street, the site of the Tenement Museum, and where Dora Meltzer was believed to have had practiced fortune-telling. (Photo: Fletcher6/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

For the Tenement Museum, the search is still on, and the museum plans on future public talks about Dora and her peers in the hopes that the publicity lends more clues, as it did before. “Several years ago someone had been in touch because of a blog post that was up, but unfortunately their number was lost,” says Polland. They’ve also been reaching out to leads gained from ancestry.com.

In the past, the museum believed Dora’s first name to be an alias–census records showed that a Meltzer family, but no Dora, lived at the flyer’s address. Recently, that changed: the museum not only found a picture of an older woman named Dora Meltzer from 1919 that could be the fortune teller, but also uncovered census evidence that she lived at Delancey Street, around the corner from Orchard Street, with her husband and children.

Poland speculates that Dora may have used 97 Orchard Street as her business address. She could have been protecting her identity, rushing over from her own house if a customer happened to show–after all, her business hours were broadly advertised as “9 A.M. To 10 P.M.” Or she may have helped her relatives at their home there during the day, making it a practical office.

While Dora’s full identity has yet to be uncovered, there are promising leads: a descendant of former 97 Orchard Street occupants recently approached a Tenement Museum educator after a talk, looking to find more about their family. Their last name: Meltzer.

Update, 12/4: An early version of this article stated that Edward Portnoy works for the Center for Jewish History. Portnoy actually works for the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. We regret the error.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook