Before the Garden Gnome, the Ornamental Hermit: A Real Person Paid to Dress like a Druid

An English hermitage illustrated in “Merlin: a poem” (1735) (via British Library)

While some gardeners might now throw in a gnome statue among their flowers and shrubberies, back in the 18th century wealthy estate owners were hiring real people to dress as druids, grow their hair long, and not wash for years. These hired hermits would lodge in shacks, caves, and other hermitages constructed in a rustic manner in rambling gardens. It was a practice mostly found in England, although it made it up to Scotland and over to Ireland as well.

Gordon Campbell, a Professor of Renaissance Studies at the University of Leicester, recently published The Hermit in the Garden: From Imperial Rome to Ornamental Gnome with Oxford University Press. It’s the first book to delve into the history of the ornamental hermit in Georgian England. As Campbell explains in this video for the book:

“Recruiting a hermit wasn’t always easy. Sometimes they were agricultural workers, and they were dressed in a costume, often in a druid’s costume. There was no agreement on how druids dressed, but in some cases they wore what we would call a dunce’s cap. It’s a most peculiar phenomenon, and understanding it is one of the reasons why I have written this book.”

How the live-in hermit came to be a fashionable touch to a splendid garden goes back to the Roman emperor Hadrian with his villa at Tivoli, which included a small lake with a structure in it built for one person to retreat. When the ruins of this early hermitage were unearthed in the 16th century, it was suggested that Pope Pius IV build one for himself, which he did at the Casina Pio IV. Yet from here it gradually verged away from religious devotees isolating themselves for spiritual reflection to hermitting being an 18th century profession for those willing to put up with the stipulations.

As Campbell cites from an advertisement referenced in Sir William Gell’s A Tour in the Lakes Made in 1797, ”the hermit is never to leave the place, or hold conversation with anyone for seven years during which he is neither to wash himself or cleanse himself in any way whatever, but is to let his hair and nails both on hands and feet, grow as long as nature will permit them.”

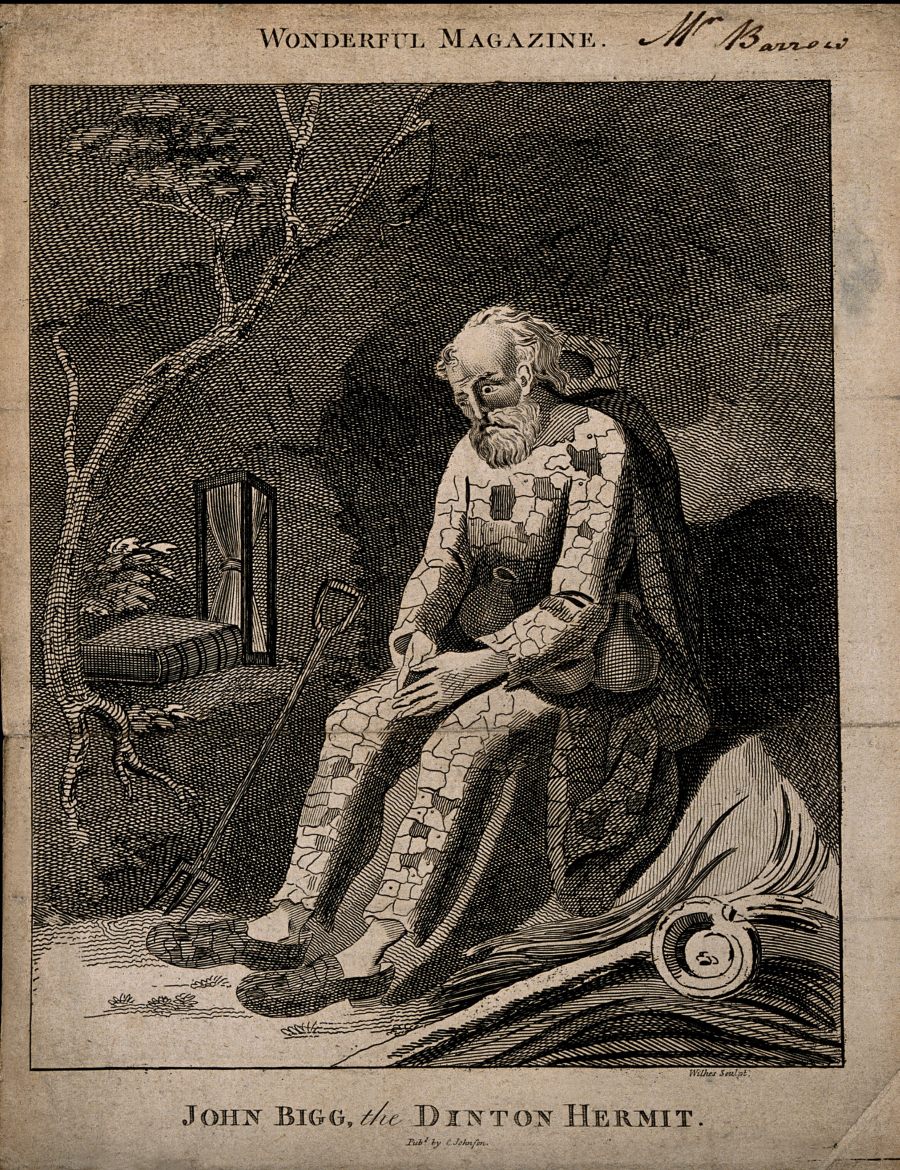

John Bigg, the Dinton Hermit. Not a garden hermit, but of same era (via Wellcome Library)

John Bigg, the Dinton Hermit. Not a garden hermit, but of same era (via Wellcome Library)

John Bigg, the Dinton Hermit (via Wellcome Library)

John Bigg, the Dinton Hermit (via Wellcome Library)

Others asked that their hermits not wear shoes or even to entertain party guests with personalized poetry or the serving of wine. It might seem like a whimsical garden feature, but in fact it was all about that most celebrated of Georgian England emotions: melancholy. Introspection and a somberness of spirit were prized among the elite, and the roles they asked their hermits to play embodied this. A 1784 guide to the Hawkstone estate in Shropshire belonging to Sir Richard Hill describes its resident hermit:

“You pull a bell, and gain admittance. The hermit is generally in a sitting posture, with a table before him, on which is a skull, the emblem of mortality, an hour-glass, a book and a pair of spectacles. The venerable bare-footed Father, whose name is Francis (if awake) always rises up at the approach of strangers. He seems about 90 years of age, yet has all his sense to admiration. He is tolerably conversant, and far from being unpolite.”

An English hermitage illustrated in “Merlin: a poem” (1735) (via British Library)

At other hours, the Hawkstone hermit was replaced with a mannequin, or perhaps, Campbell speculates, an automaton. Some estate owners who couldn’t afford, or did not want, a real live hermit sometimes set up the hermitage as if its resident had just left. Others used the hermitages themselves.

The ornamental hermit vanished at the end of the 18th century. In The Hermit in the Garden, Campbell chronicles the remains in a “catalogue of hermitages,” listing whether they are destroyed, extant, or never built at all. However, the humble hermit may not have left us entirely. As Campbell argues, “the garden hermit evolved from the antiquarian druid and eventually declined into the garden gnome.”

An 18th century hermitage that survives in Manor Gardens Eastbourne, East Essex (photograph by Kevin Gordon)

The Hermit in the Garden: From Imperial Rome to Ornamental Gnome (2013) by Gordon Campbell is available from Oxford University Press.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook