The Man Who Began America’s Yurt Craze

A Harvard-educated visionary who chose to live in remote New England and spread the gospel of yurts via mail.

Bill Coperthwaite, who died in 2013, in his yurt in 2003. (Photo: Kevin Bennett/Bangor Daily News)

The story of yurts in America begins 44 years ago, when Bill Coperthwaite was leafing through National Geographic magazine and came upon a series of Kodachrome photographs that changed his life. Pictured were clusters of round tents sprouted out of the dusty steppes of outer Mongolia like little, white mushrooms. The article’s author, William O. Douglas, a former associate justice of U.S. Supreme Court, discovered these portable igloo-shaped shelters all over Central Asia, in cities as well the snowy, roadless plains. Known as gers (rhymes with “airs”)—or, yurts, as the Russians called them—the tents featured pictures of Lenin and “were as Mongolian as apple pie is American.”

Near the end of his 37-page spread was a freeze-frame sequence, showing a group of herdsmen gathered in a circle. The group unfolds an accordion-like lattice to form a low cylindrical wall, fits long poles over top almost like the ribs of an umbrella, and then covers the entire structure with heavy, woolen felt and white canvas. The caption reads like a perky sales pitch: “Prefab home, a ger goes up in less than an hour.”

At the time, the man who would transform the yurt into a potent countercultural symbol and sometimes punchline, had never ventured beyond Mexico, let alone Mongolia.

The view of Coperthwaite’s yurt, photographed for the publication Home Work. The blue orb on the spire is a Japanese-style glass fishing float. (Photo: Dan Neumeyer/Courtesy Shelter Publications)

Coperthwaite built his first wooden yurt that year, at the Meeting School in Rindge, New Hampshire. He was 22 years old. Coperthwaite taught math, and yurt-building offered a hands-on lesson in geometry. Soon, though, he became transfixed. He began adapting the traditional designs by building yurts with outward sloping walls and using wood instead of wool. He purchased an island off the coast of Canada with the hopes of establishing a more permanent residence, but his down payment was returned upon arrival and so Coperthwaite settled on several hundred acres along the easternmost stretch of Maine’s coastline (or Down East, as it’s sometimes known). On November 25, 1963, Coperthwaite built an A-frame. His students canoed in a flotilla of lumber, and he set up a living museum, known, as he told one reporter, the Sea Farm Folk School.

Five years later, in the midst of his doctorate thesis, “A Traveling Museum of Eskimo Culture,” Coperthwaite built a yurt outside the Graduate School of Education at Harvard. These were no geodesic domes and did not require space-age materials that leaked on your fellow communards in the rain. Yurts proved to be a deeply attractive, durable design that appealed to a restless generation.

The opening pages to William O. Douglas’s National Geographic article about Mongolia. (Photo: National Geographic/Courtesy Peter Andrey Smith)

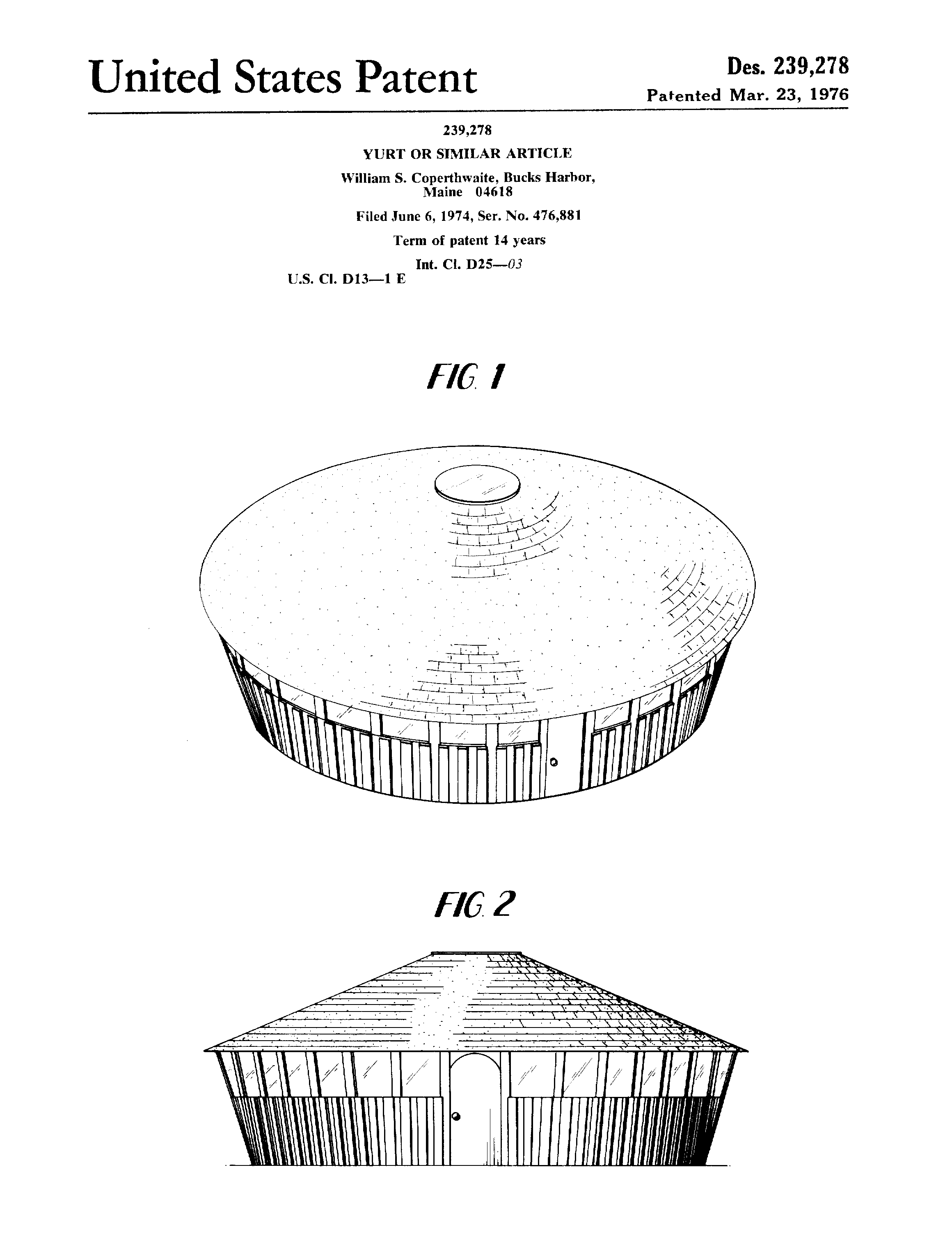

By 1974, yurts attracted a small but devoted following, nestled amidst the converted churches and the domes and the dreamcatchers in Lloyd Kahn’s Shelter, an influential early survey of counterculture structures. (What is a yurt, exactly? In the taxonomy of tents, yurts are distinguished most clearly by their shape—a sturdy round base with a gently-sloped roof. They are circular dwellings with a collapsible frame, sometimes set up more permanently. Geodesic domes are a more specific, and recent phenomenon, dating to 1952 and describes a series of continuous interlocking triangles or hexagons that take on a spherical shape.) Publisher’s Weekly ran a review calling yurts “the newest thing in housing.” Coperthwaite must have realized he was at the epicenter of a growing trend; he secured a patent on his shingled “yurt or similar article” in 1976, and began teaching workshops at his retreat in Maine.

It was more than just a fancy tent to Coperthwaite. As one of his friends, Peter Forbes, the author of a book, A Man Apart: Bill Coperthwaite’s Radical Experiment in Living put it, the beautiful and inexpensive dwellings were part of a broader vision for democratic living. Coperthewaite opens his 2003 book, A Handmade Life, by explaining his devotion to making indigenous crafts, but what he really wanted was to share the exuberance in making, “encouraging people to seek, to experiment, to plan, to create, and to dream.” Of course, not everyone saw it that way. Forbes writes that two sailors once saw Coperthwaite emerge from the fog in his wooden canoe—his white hair frazzled like the seed-head of a dandelion—and thought they’d discovered a hermit.

Bill Coperthwaite’s 1976 patent for a “Yurt or similar article”. (Photo: Google Patents USD239278S)

This unwillingness, and maybe, at times, his inability, to leave a place he made his home would be the defining characteristic for much of his life. His lifeline was the postal service—the only reliable way to reach him—and, from the local post office, he would mail out thousands of maps and plans for building domed-shaped shelters.

Yurts in the Mongolian countryside. (Photo: Francisco Anzola/CC BY 2.0)

Burning Man, where yurts are popular. (Photo: Hawaii Savvy/CC BY 2.0)

By the late 1990s, yurts had became an outdoor status symbol. They sprouted up at backcountry ski lodges and state parks. Some of his former students went on to found companies, and it was now possible to buy yurts with NASA-inspired, fire-resistant coverings. The Ace Hotel in Palm Springs opened a spa inside a yurt. In Utah, the Yurt at Solitude offers slope-side, fine dining at $125 a meal.

What began, innocently enough, with a young math teacher wowed by the Mongolian landscape had opened up a kind of clumsy cultural appropriation. When yurts went up during the Occupy Wall Street protests, Drew Hayden Taylor, a Native American columnist, wrote, “Why do these people have to drag us, and more importantly, the domiciles we traditionally used to inhabit, into their rumblings?”

I wondered what Coperthwaite made of it all, and so one day, I went to find out.

Bill Coperthwaite’s yurt in Maine. (Photo: Peter Andrey Smith)

Driving to the far reaches of coastal Maine can be lovely when you could see more than a couple hundred yards past your face. The winding, two-lane road cuts through blueberry barrens, damp pine forests, and small towns where people congregate around gas pumps, arms slung out the windows of their pickup trucks. His village—Bucks Harbor, located within the town of Machiasport—had suffered the closing of the fish-packing plants and regional depression. The morning I visited, a lone figure was stooped over the mud flats, raking for bloodworms or steamer clams. Suffice it to say, he’d made his yurts inaccessible, almost by design. Visitors parked along a muddy, dirt road and walked a mile-long sawdust path that threaded through maples and balsam firs, through bunchberry and sphagnum moss, over a beaver pond. Then, in a clearing, a circular, the four-tiered wooden yurt rose, its four sloping roofs meticulously shingled. In the silvery, barren fields, it looked like a wooden spaceship fashioned in Middle-earth. A blue orb glistened from its spire.

From above, the yurt resembled a silver satellite dish. On the ground, there was nothing of the sort: No television, no plumbing, no landline. (No Lenin photos either, so far as I could tell.) At his ground-floor studio, Coperthwaite kept hand-planes, axes and adzes, stools. Wood shavings littered the floor. He had carved wooden bowls and wooden spoons. He made birch brooms and paddles. Outside, he constructed a yurt outhouse, an outdoor kitchen with a dome-shaped roof. Everything there breathed of the past: In the yurt library, I found a poster of a woman dancing in the nude with a bull moose (the moose was also nude). Coperthwaite appeared to be preparing for his 90s by splitting firewood in advance, and these wood piles were stacked about—constructed with onerous precision. By many accounts, a reflection of his personality.

Inside the spacious, ground-floor workshop at Bill Coperthwaite’s yurt. (Photo: Peter Andrey Smith)

I never crossed paths with the man who brought the yurt to North America, not that day, or any other time. Later, I read that Coperthwaite had a reputation for being gentle and insistent. When the pilgrims of simply living flocked to his yard, he’d explain that he wasn’t going back to the land, he was getting down to earth.

But was that it? Here was a Harvard-educated, yurt-dwelling philosopher, a grown man playing a poverty in one of the nation’s poorest counties, someone who felt spiritually cleansed by the ritual of making things from scratch. That, it seemed, was a privileged choice—a fantasy not everyone could afford.

Tools in Coperthwaite’s workshop inside his yurt. (Photo: Peter Andrey Smith)

When I finally unearthed the original National Geographic story several years later, I learned that even in 1962, the pop-up gers were factory-made. Perhaps Coperthwaite was loath to admit the handmade world he so revered had spawned from a cheap copy. I will never really know. Shortly before Thanksgiving in 2013, Coperthwaite was killed when his car careened off the road and wrapped around an oak tree.

But I suspect he saw things in simpler terms. When I first mailed him a letter, Coperthwaite replied with an invitation sent in the form of a hand-drawn map. He was alone, yes, but eager to share the exuberant life he had created in his solitary kingdom. The return address simply said, “Bill, Machiasport, 04655.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook