The Manhattan Burial Crisis of 1822 Makes Every Cemetery Today Seem Amazing

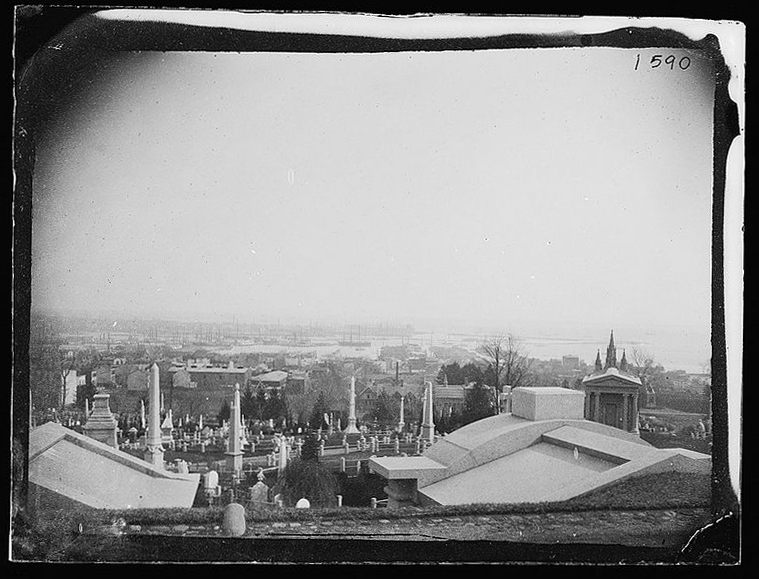

“View from Green-Wood Cemetery, Brooklyn,” 1881, by Rudolph Cronau. (Image: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

The 300-year-old graveyard at Trinity Church in Lower Manhattan today serves as a respite from the frenzy of the Financial District. Small groups of tourists wander the stone pathways, stepping occasionally onto the manicured lawn to peer more closely at tilting eighteenth century tombstones of notable New Yorkers, like Alexander Hamilton, laid to rest in Trinity in 1804 after succumbing to the wounds from his duel with Aaron Burr. A cursory examination of the standing tombstones and stone memorials might lead one to guess the two and a half acre yard holds the remains of perhaps one hundred individuals. Little evidence survives that by 1822, an estimated 120,000 bodies lay underneath.

One official report from that year did not bother to count. “The number of persons buried in this yard down to 1822 cannot be computed,” read the report. “But it is almost beyond belief.” Responding to the “offensive exhalations” that rose from the yard in the late summer, the Common Council and its Board of Health passed a resolution in August prohibiting the further digging of graves at Trinity. Passersby complained of the awful stench, as did residents on nearby Wall and Lumber streets. The source of the smell was unmistakable–the decomposition of tens if not hundreds of shallowly buried corpses. Since July of that year an outbreak of yellow fever had assailed the old neighborhoods south and west of the church.

Trinity Church, circa 1920. (Photo: Library of Congress)

As the summer of 1822 turned to autumn, New York’s body problem only worsened. A terrible odor emanated from Trinity Churchyard, lingering over Broadway and Rector Street. On the night of September 22nd, a local resident would later write in a letter to a leading doctor investigating the causes of that year’s yellow fever epidemic, one man–a Dr. Rosa–decided to take matters into his own hands. The desperate Dr. Rosa recruited a group of men to cover the graveyard in quicklime to speed up the process of decomposition. So offensive was the smell that the men, Dr. Rosa noted later, vomited “freely” as they worked through the night.

Still, despite the city’s ban on new burials, many of the bodies were only interred two or three feet under the ground, and the odor of decay persisted. The ban at least tended to one problem–the near constant uncovering of buried bodies. In order to find new room to bury the dead in the vastly overcrowded yard, gravediggers would poke the ground with iron rods searching for thoroughly decayed and thus softened coffins to unearth. Once dug up, these older remains would then be removed to and piled in the graveyard’s charnel house, opening up space underground for the more recently dead.

A marble marker at New York City Marble Cemetery used for those vaults without monuments. (Photo: Beyond My Ken/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

New York’s burial crisis was not limited to the graveyard at Trinity. Dire reports were also issued on the conditions of the burial grounds at the North Dutch Church on William and Fulton streets, the Middle Dutch Church on Liberty and Nassau, and at St. Paul’s just north of Trinity. Nor was the crisis due solely to the influx of the dead in the wake of yellow fever epidemics, though the outbreaks exacerbated the problem. Contemporary observers noted that the dismal state of Trinity predated the first reported cases of yellow fever in the 1822 epidemic. How could Trinity Church, along with Manhattan’s other 21 burial grounds, possibly keep up with the city’s rapidly growing population of the dead?

Founded in 1697, the Episcopal Trinity Church began to bury its dead in an adjacent lot that had been established 30 years prior as a public burial ground for New Amsterdam. Over the next 125 years, Manhattan’s population grew twenty-five fold. By 1822, Trinity sat in the middle of a thriving commercial neighborhood, its modest yard holding more than a century’s worth of bodies.

New York City Marble Cemetery, on 2nd Street between 1st and 2nd Avenues. (Photo: Eden, Janine and Jim/Flickr)

The development of New York continued without pause for the dead, even in times of epidemic. Greenwich Village, still very much a village in the early 19th century, became a destination for Lower Manhattanites fleeing the “infected districts” during outbreaks of yellow fever. Nonetheless, as the population soared and available space shrank, residents and local leaders alike knew that the city needed to address the bodies, ceaselessly piling up. In the burgeoning metropolis, even Manhattan’s underground was quickly becoming a real estate commodity.

While the odor of decaying bodies was unpleasant enough, New Yorkers also worried that the smell was quite literally making the people of the city sick. When the city suffered its five outbreaks of yellow fever between 1798 and 1822, the cause of the disease was still unknown. (Not until the late 19th century would doctors prove mosquitoes to be its carrier). In a desperate attempt to locate and stop the source of the 1822 epidemic, prominent New York doctors and city leaders noted that the fever’s first case was but a block away from Trinity on Washington and Rector streets. And until the outbreak ended with the first frosts of November, the disease would remain mostly concentrated in the neighborhood just west to the graveyard. Miasma, or polluting vapors that might arise from filth or decay, was long thought to be the cause of disease. The decaying bodies in Trinity churchyard, many of which belonged to victims of yellow fever, and the “noxious air” they produced, might very well be sickening local residents. Manhattan’s burial crisis became a public health crisis too.

The New York Marble Cemetery, with its entrance at 41 Second Avenue, in Manhattan’s East Village. (Photo: Beyond My Ken/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

The city’s ban on further burials in Trinity’s yard was the first of many attempts to remedy Manhattan’s body problem. The same year, an ordinance passed forbidding burials south of Canal Street, save for those in already established family vaults. As the city grew, the burial boundary shifted upwards; first, in 1839, to 14th Street and by 1859, to 86th Street. To alleviate the strain of the public lot at Trinity and to lessen the believed harmful effects of miasma, the city continued to bury its indigent dead outside of the city limits in potter’s fields, including those located in what is now Washington Square Park and Bryant Square.

In 1830 and 1831, two new cemeteries–the first nonsectarian burial grounds in New York–also sprang up on what was then the edges of development: the New York Marble Cemetery in 1830 on Second Street near the Bowery and the similarly named New York City Marble Cemetery, a block away. (Both cemeteries still exist, but are only occasionally open to the public). In order to maximize space, bodies were stacked in thick family vaults underground. Above ground, the cemeteries, although not large, were pleasant places dotted with sporadic monuments reading the family names of those buried below. But soon enough Manhattan grew up around these spaces, and the vaults quickly filled up.

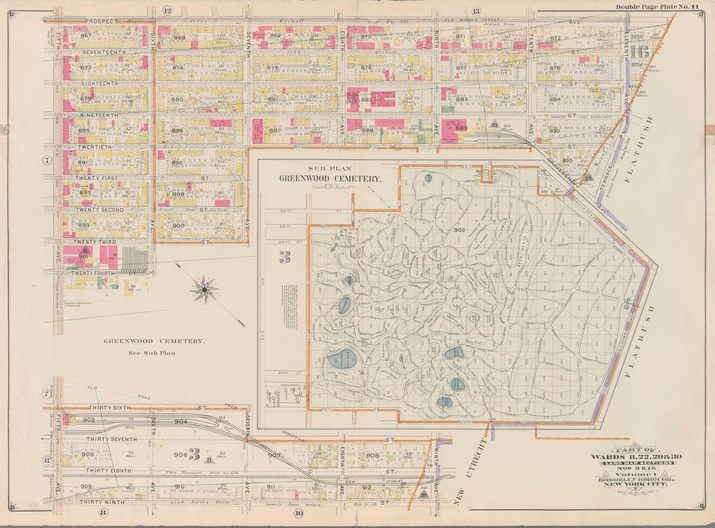

Map of Green-Wood Cemetery and surrounding streets, circa 1899. (Image: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Of course, New Yorkers kept dying. Conceiving of the future of the city would involve not only accommodating its rapidly growing population, but also properly and sanitarily housing its dead. Not only was the ghastly scene at Trinity churchyard in 1822 unbefitting for an economic and cultural capital such as New York, it was intolerable for New Yorkers who wished to secure in perpetuity resting spots for their loved ones and themselves. But eternity was not, as it is now, a concept easily protected in Manhattan. Graveyards–prime real estate–were regularly sold to the highest bidders. Try as they may, the congregation of the German Reformed Church at University Place and 12th Street could not stop the sale and removal of bodies from their churchyard, a case they took to court in 1846 and lost.

Instead, New Yorkers looked to a new model of cemetery, like Mount Auburn outside of Boston and Laurel Hill in Philadelphia, and judged the rolling hills of Brooklyn just across from Lower Manhattan to be safe enough from the encroachment of urban development. In 1838, a group of prominent civic leaders founded Green-Wood Cemetery on 178 acres of land bought from old Brooklyn farming families. Over the next several decades, the “rural” cemetery would add another 300 acres, a far cry from the two and a half on which Trinity’s original churchyard sits. (In 1842, Trinity Church would establish its own rural cemetery in what is now Washington Heights). The cemetery would abandon not only the cramped dreariness and decay of the old churchyard, but also any sense of the city.

David Bates Douglass, the cemetery’s planner and its first president, designed Green-Wood as the ideal romantic landscape, sculpting its hillsides, planting trees and other vegetation, and giving its curving paths names like Evergreen, Petunia, Snowberry, and Verdant. By 1876 Harper’s Weekly could boast that Green-Wood was “the largest and most beautiful burial place on the continent.”

An early photograph by George Bradford Brainerd of the Mount, Green-Wood Cemetery, Brooklyn, circa 1872-1887. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

One needed to pay in order bury their dead, of course, in such a lovely, spacious cemetery. The problem of the impoverished dead and the public burial ground continued to vex city officials, and too, occasionally horrified New Yorkers. In 1858, a letter to the editor of the New York Times hoped to “call attention to our City authorities to the … coffins, skulls, and decayed bodies lying exposed on the corner of Fiftieth-street, and fourth-Avenue,” the site of a potter’s field. “Is our city always to be disgraced by some public exhibition?” the writer bemoaned.

Soon enough, in 1869, the city of New York would purchase Hart Island, which to this day remains the city’s public burial ground. The corpses of Manhattan, once a public crisis, would properly go underground, making room for a whole new set of urban pestilences and pollutants to emerge to beleaguer the city-dweller.

Today the grounds at Trinity, removed mostly from the hubbub of the surrounding neighborhood, feel appropriately respectful for a graveyard–at least by our modern standards. But the ways we now think about a ‘proper’ cemetery–and city too–were in large part shaped by a burial crisis nearly 200 years ago and the responses it invoked. For contemporary New Yorkers, routine assaults on the senses are considered something of an unavoidable byproduct of urban living. But the state of Trinity churchyard in 1822 is now hard to imagine. Today’s city dwellers are unlikely to think of the disposal of human corpses as a pressing urban problem, nor include the odor of bodily decay on a list of urban nuisances. But they should be grateful to early 19th century New Yorkers, who in grappling with their newfound realities of city life, solved the problem of the bodies–or at least, pushed the issue out of sight and mind.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook