The Persistent Racism of America’s Cemeteries

Not only is segregation still an issue but also America risks losing important history in its forgotten graveyards.

A view of Greenwood Cemetery in Waco, Texas. (Photo: © Google 2016)

In 2016, the city of Waco, Texas issued an order to remove a fence in the city’s public burial ground, Greenwood Cemetery. But it wasn’t just a cosmetic change: Using a forklift and power tools, City of Waco Parks & Recreation staff cut apart the chain-link fence that had been used to divide the white section of the cemetery from the black section.

The cemetery had been racially segregated since it opened in the late 1800s. It was operated by two sets of caretakers, white and black, until the city took over the cemetery about 10 years ago.

Waco is not the only Texas community to struggle with the surprisingly robust ghost of Jim Crow: This spring, the cemetery association of Normanna, Texas, about an hour outside Corpus Christi, was sued by the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund for barring a white woman from burying the ashes of her Hispanic husband there. Although the cemetery association later relented, the U.S. Department of Justice is investigating. No Hispanic people are buried within the Normanna cemetery—there is one sole tombstone with a Spanish surname, located just outside the cemetery’s chain link fence.

San Domingo Cemetery in Normanna, Texas. (Photo: © Google 2016)

Until the 1950s, about 90 percent of all public cemeteries in the U.S. employed a variety of racial restrictions. Until recently, to enter a cemetery was to experience, as a University of Pennsylvania geography professor put it, the “spatial segregation of the American dead.” Even when a religious cemetery was not entirely race restricted, different races were buried in separate parts of the cemetery, with whites usually getting the more attractive plots.

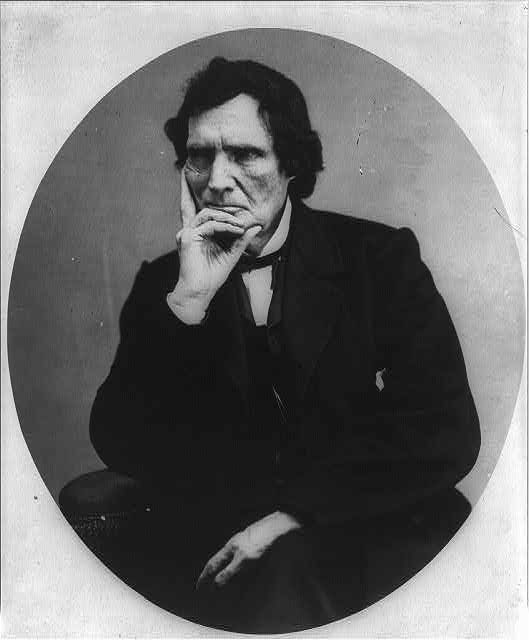

Some white Americans did fight against this policy. Abolitionists, such as Thaddeus Stevens, a radical Republican and chair of the House Ways and Means Committee during the Civil War, insisted on being buried in a non-segregated burial ground. Stevens chose to be buried in an interracial cemetery in Lancaster, Pennsylvania after his death in 1868. The issue of interracial eternal repose was so important to him that he wrote it into his own epitaph. His tombstone read: “I repose in this quiet and secluded spot, not from any natural preference for solitude; but, finding other cemeteries limited as to race, by charter rules, I have chosen this that I may illustrate in my death, the principles which I advocated through a long life, equality of man before the Creator.”

Abolitionist Thaddeus Stevens. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-USZ62-63460)

From the 1920s through the 1950s, courts did not consider cemeteries to be “public accommodations,” so cemeteries did not qualify for special civil rights protections. But in May 1948, the Supreme Court ruled in Shelley v. Kraemer that state enforcement of racially restrictive covenants in land deeds violated the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment. This had a major impact on the ability of blacks to buy houses in white neighborhoods, but it also affected the de-segregation of cemeteries. Whites-only restrictions on cemetery plots could no longer hold up in court. As a sign of the slowly-changing times, several interracial cemeteries appeared in the 1950s. Charles Diggs, Sr., a black undertaker and florist in Detroit, bought land to create an interracial cemetery just outside the city in 1953. Mount Holiness Cemetery in Butler, New Jersey, also promoted itself as an interracial cemetery in black newspapers like The New York Age in the 1950s.

But since blacks and whites continued to live and worship separately, such initiatives were few and far between.

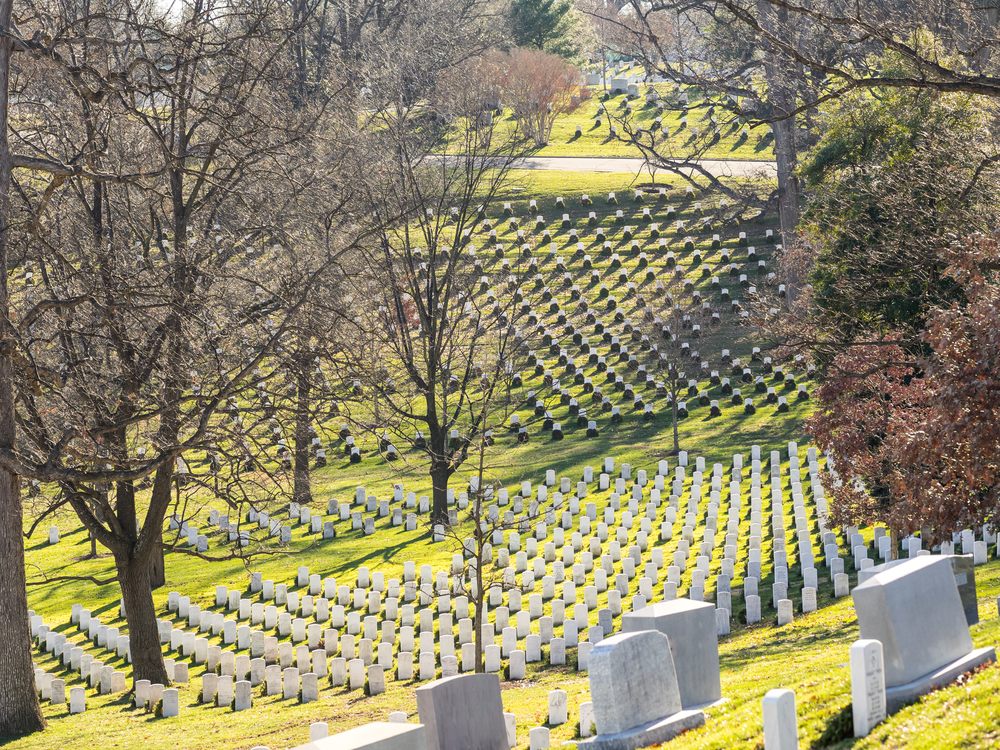

Arlington National Cemetery was desegregated in 1948. (Photo: Sergio TB/shutterstock.com)

Just a few weeks after SCOTUS ruled in Shelley v. Kraemer, President Harry Truman issued Executive Order 9981, which officially desegregated the military. Although it took years to desegregate battlefield units, the order went into immediate effect at Arlington National Cemetery. One of the first black veterans to be buried in a formerly white section of Arlington was Spottswood Poles, a star of Negro League baseball who enlisted with the infamous Harlem Hellfighters, an all-black unit that fought in the trenches of France during World War I. Poles earned five battle field star decorations, as well as the Purple Heart, for his military service. He was interred at Arlington with full military honors in 1962.

As the racial composition of communities changed over time, many black cemeteries became neglected and forgotten, and the resting places of countless unsung heroes of America’s black past quietly disappeared. In 2014, U.S. Senator Bob Casey called on the Veterans’ Administration to establish a public database listing where all black Civil War veterans were buried, because few such cemetery records exist. Since many black graves are unmarked, recording and cataloguing their locations requires ground-penetrating radar and high-precision GPS. Several months ago, over 800 unmarked graves were uncovered using this technology at a black cemetery in Atlanta, demonstrating the potential for similar discoveries in cemeteries and forgotten burial grounds across the country.

Spottswood Poles in 1913. After serving in World War One, Poles was buried in Arlington National Cemetery in 1962 with full military honors. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Like the city councilors of Waco, many community groups and civic associations are currently engaged in the difficult, lengthy, and expensive tasks involved in unearthing black history. In the process, they are discovering that addressing the wrongs of the past is often more complicated than simply removing the physical reminders of Jim Crow that haunt our landscape. The traces of the past are sunk deep into the earth, but with the right tools, it’s possible to make them visible.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook