The Popular Victorian Clubs That Yearned To Fill Europe With Hippos

In the 19th century, dozens of Acclimatization Societies wanted to stock Europe with exotic beasts—and the colonies with tame ones.

On November 15th, 1877, a select group of dedicated people filed into the Reading Room of the New York Aquarium for their annual meeting. For the next few hours, they updated each other on the milestones they had achieved that year. One man described how he had loosed skylarks, chaffinches, and pheasants in Central Park, and watched a previous crop of English sparrows “multiply amazingly.” A second voiced his hope that the English titmouse and the blackbird could soon join them. Yet another made an impassioned argument for the movement of the California brook trout, which he called “the best of our own fishes,” into New York waters.

Today—as we laud native species, fight invasive ones, and secure our borders against trafficked wildlife—this behavior seems intrinsically harmful. But this wasn’t a group of proto-eco-terrorists. It was the American Acclimatization Society—one of dozens of perfectly legal groups dedicated to spreading species around the world. For a few decades at the end of the 19th century, “acclimatization,” or intercontinental species-swapping, was all the rage throughout Europe and its colonies. Although it was eventually replaced by sounder ecological strategies, its strange legacy remains.

The godfather of acclimatization was a French anatomist named Isidore Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire. Originally a specialist in so-called “structural monstrosities” (what we today would call congenital abnormalities, like cleft lips), Saint-Hilaire eventually found himself in a senior position at the National Museum of Natural History in Paris. While there, he developed certain philosophical views about the role of animals in society—namely, that they and humans are locked into a kind of mutually beneficial contract that enabled their true destinies.

Under the terms of this agreement, certain animals provide humans with undying devotion, along with other more tangible goods like fur, feathers, and meat. In return, humans allow these animals a passenger’s-seat view of the progress of society and the triumph of reason, something the animals couldn’t pull off on their own. Even wild animals, he argued, could choose to become domesticated—opting into what, in Saint-Hilaire’s argument, was a good deal for all involved.

Under this philosophy, it only made sense that the French should bring as many of these animals as possible into their country, in order to give them the chance to fall in step. They should also send their own domestic animals abroad, to spread the fruits of this bargain to other countries. In 1854, Saint-Hilaire established La Societé Zoologique d’Acclimatation—the first acclimatization society, headquartered in the National Museum. Within a few years, they had opened a side branch in French Algeria, as well as the “Jardin d’Acclimatation,” a zoo in Paris filled with all the animals that might soon roam France—Algerian sheep, Angora goats, yaks, elephants, and hippos. By 1860, the society had over 2,500 members, including diplomats, scientists, foreign heads of state, and military men.

Thanks partially to La Societé’s international membership, its founding ideas quickly crossed borders. It helped that these concepts meshed so easily with many of the principals of colonialism. As acclimatization devotee Auguste Hardy once put it, in many ways, “the whole of colonization [was] a vast deed of acclimatization”—dependent on the idea that European powers knew what was best for the entire world, and deserved both to spread their own way of life to all four corners of the globe, and to harvest all of the earth’s fruits.

By 1900, there were over fifty Societies, swapping species everywhere from Algiers to Tasmania. Think of a rampant colonial power, and chances are that people there were meeting regularly to scheme about how to spread different creatures to their colonies, and bring others back.

Many of these efforts were, predictably, spectacular failures. An early shipment of camels to Australia, to help travelers cross the arid interior, was met with tragedy when bad weather killed all but one (that camel, named Harry, lived a life of celebrity until he accidentally killed his owner, John Horrocks, by headbutting a gun while Horrocks was cleaning it). Ostriches similarly failed to thrive there. The founders of the British Acclimatization Society, who believed that the country’s growing food crisis could be solved by the introduction of exotic fish and big game, threw an enormous banquet every year from 1860 to 1865, featuring tables piled high with German boar, Syrian pig, East African eland, and Australian kangaroo. But they never successfully imported anything more impressive than the North American gray squirrel, which haunts them to this day.

Others were too successful. Australia was a popular places to send European species, largely because the settlers there were suspicious of the native flora and fauna and wanted to see some more familiar animals (“The swans were black, the eagles white… some mammals had pockets, others laid eggs… and even the blackberries were red,” complained one, named J. Martin, of his time there).

Members of Society there brought in blackbirds, thrushes, partridges, and rabbits, the latter of which soon overran the continent. The same thing happened with opossums in New Zealand. To fix this problem, they tried bringing in weasels and stoats, which began eating birds instead of the intended target. Both countries are still dealing with the devastation caused by these decisions.

The American society had its own share of victories and defeats. Chairman Eugene Schieffelin, a New York pharmacist, was both a bird fan and a Shakespeare obsessive, and he built many of the group’s priorities around a single pursuit—introducing every bird mentioned by the Bard into Central Park. Some, like nightingales and thrushes, died out quickly. Others flourished to the point of menace. European starlings now compete with native birds for nesting space, damage fruit trees by the millions, and even occasionally ground planes.

Thanks partly to these fiascos, the appeal of acclimatization slowly faded. More rigorous ecological theories replaced the spiritual and colonialist views of the natural world that had driven each society’s formation. Some, like Britain’s, dissolved altogether. Others rebranded, forgetting their border-crossing dreams and taking up mantles of conservation and game management.

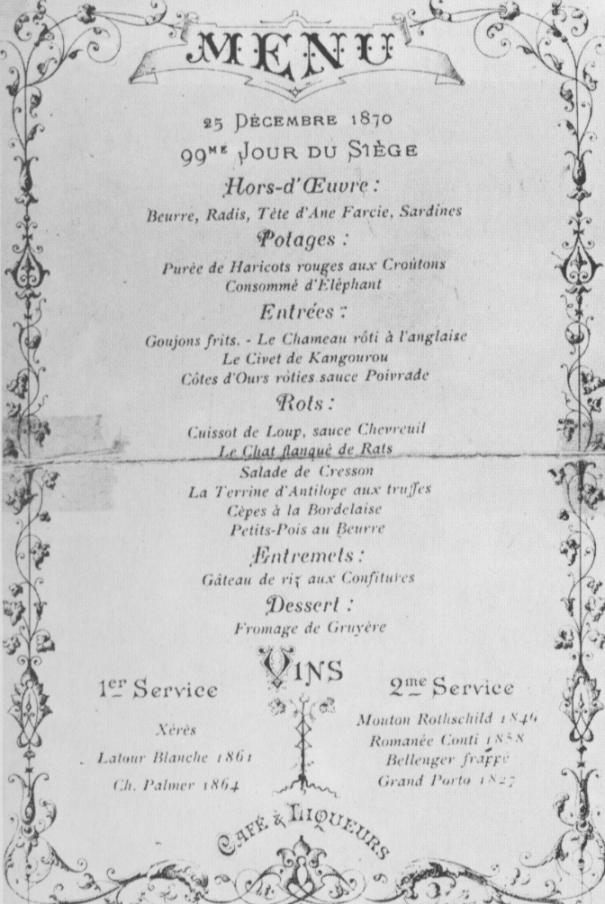

But one society—the original—came to a more brutal, if fitting, end. During the 1870 Siege of Paris, as the German army kept supplies from crossing into the city, most Parisians resorted to desperate measures, eating dogs, cats, horses, and even rats. Responding to the bourgeois’s demand for better options, luxury chef Alexandre Étienne Choron cooked most of the animals in the zoo of the Jardin d’Acclimatation for Christmas dinner, serving, among other things, fried camel, kangaroo stew, and elephant soup. (No one, in the end, wanted to dine on the hippo.) It was a far cry from the dream of exotic game roaming France—but the colonizers still had their beasts and ate them, too.

Naturecultures is a weekly column that explores the changing relationships between humanity and wilder things. Have something you want covered (or uncovered)? Send tips to cara@atlasobscura.com.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook