The Secret World War II Prison Camp for Artists

The Camp des Milles in Provence. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

The Camp des Milles in Provence. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

What happened in the picturesque town of Aix-en-Provence during World War II remains one of the darkest chapters in French history. A tile-making factory in the sleepy suburb of Les Milles would become a hellhole for thousands of Jews, whom the French collaborationist government handed over to the Nazis.

But when war broke out in 1939, the large brick building had another purpose, as an internment camp for German and Austrian expats who had been living in the South of France. And those prisoners were a very specific population—the people whom the French government feared were enemy fifth columnists and spies.

In fact they were artists.

For a period lasting until 1942, a large share of the internees were well-known artists, musicians, and intellectuals who had been persecuted under Hitler’s regime and fled to France for safety. Famed Dadaist painter Max Ernst and surrealist photographer Hans Bellmer were both prisoners, alongside dozens of sculptors, playwrights, architects, and authors.

Unlike the notorious camps in occupied Poland, Camp Les Milles was not administered by the Nazis–it was set up and run by the French. Visitors to the camp today have a window into a strange and shameful footnote from World War II, at the intersection of war, politics and art.

The tile pressing room turned performance space for the camp’s larger productions. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

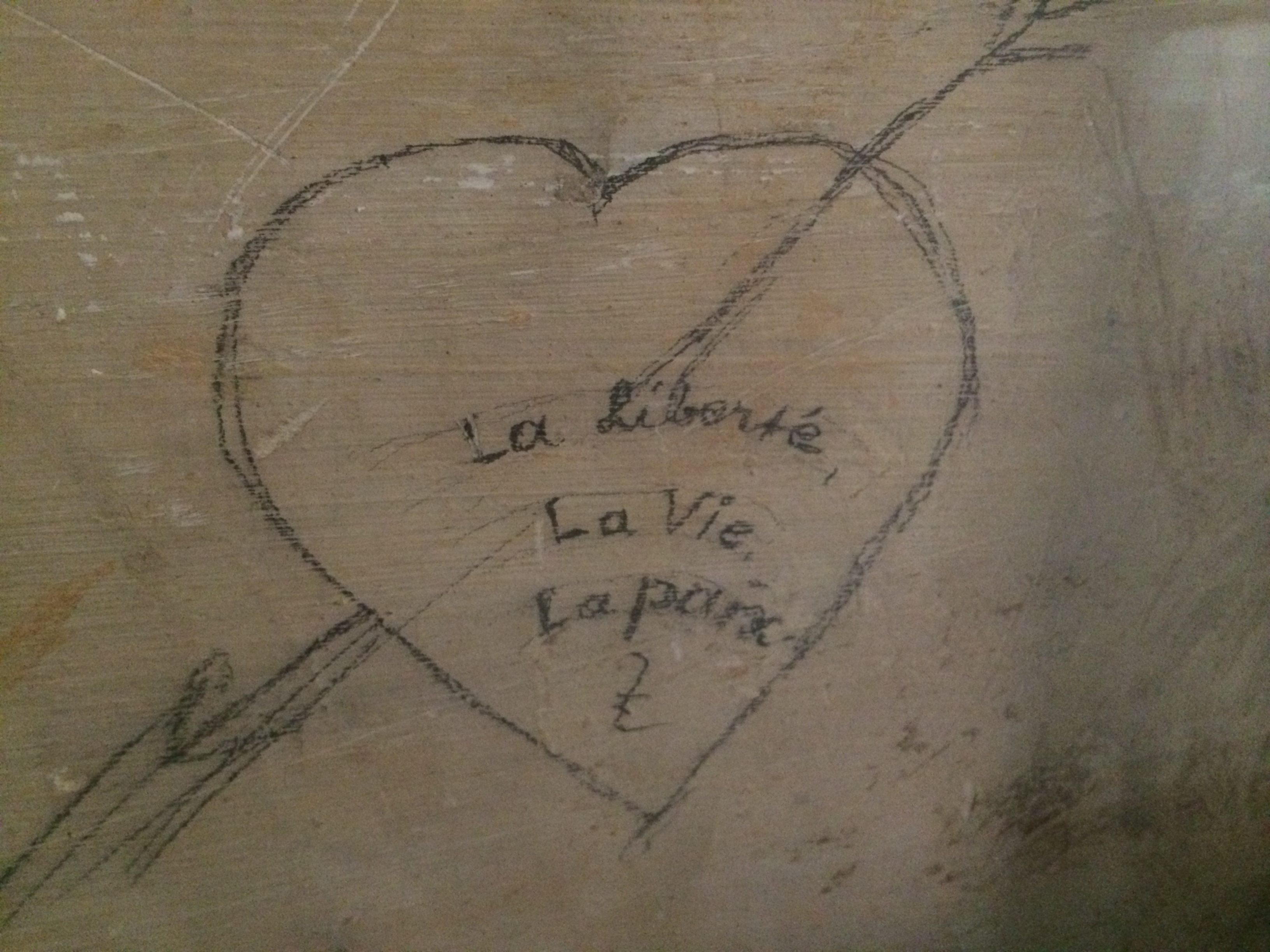

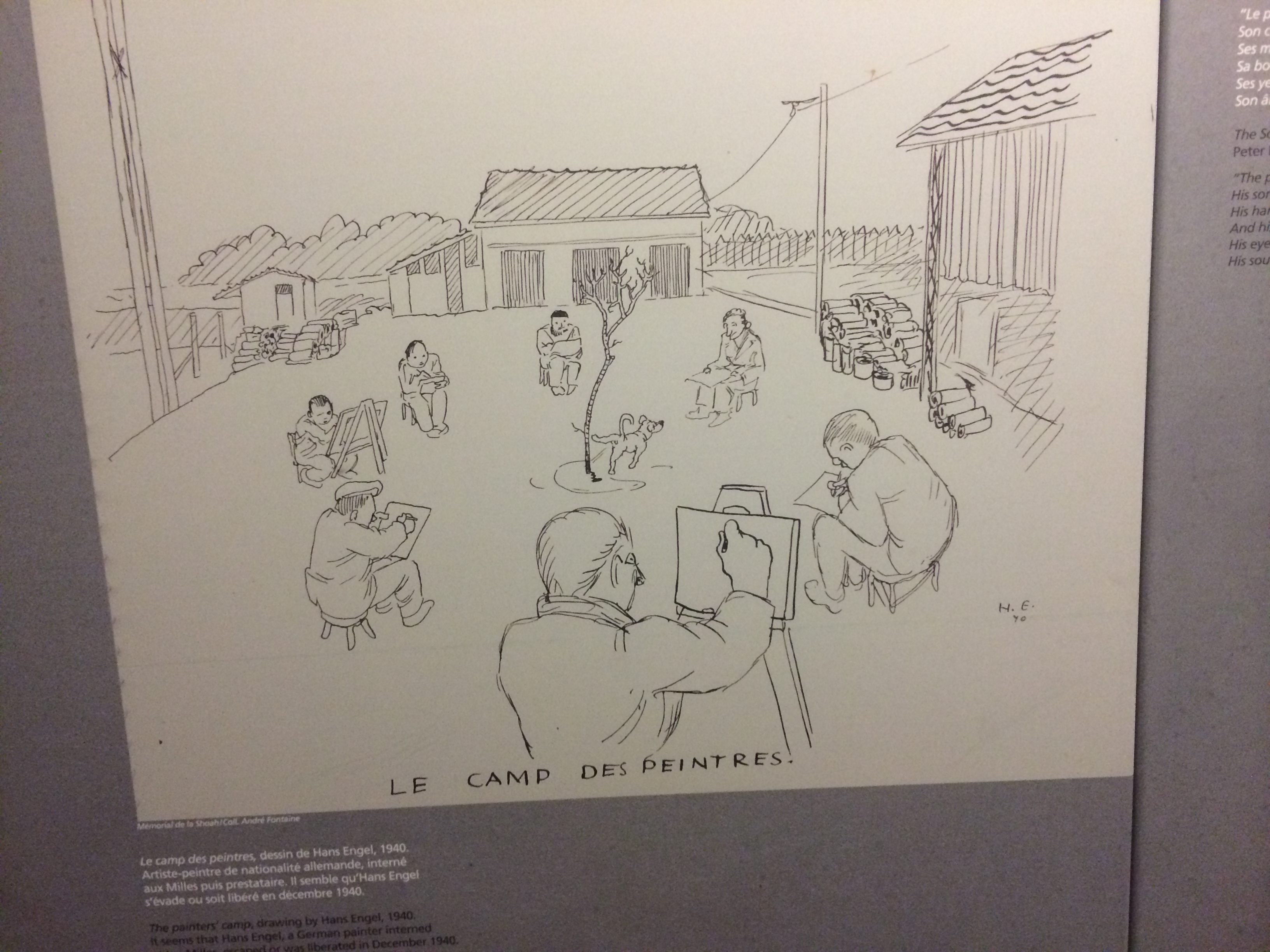

Given the creative occupations of so many of the people being held at Les Milles, it makes sense that they alleviated the boredom and frustration of confinement through artistic endeavors. Under the watch of the guards, they wrote plays, painted over 300 works of art, and decorated the walls of the tile factory with cartoons and graffiti.

One of the largest areas on the ground floor of the factory was the pressing room, where around 5,000 tiles were produced each day. (Before becoming a camp, this factory produced the red terracotta tiles found throughout southern France.) This vast space proved ideal for a concert hall. With so many creative inmates with no other outlets, the confined artistic community began to produce. Renowned musician Leonard Marker composed an opera based on One Thousand and One Nights called “Les Milles et Une Nuit.”

Playwright and musician Max Schlesinger composed a camp anthem accompanied by virtuoso pianist and conductor Adolphe Siebert:

War is hard, but not for us

We were given a rendezvous

At Les Milles and it is a pretty camp

Here we are well cared for,

Just like Milles-ionnaires.

The song was set to the music of Disney’s “Snow White,” and performed for the camp’s commandant, presumably with a sarcastic undertone.

The prisoners recreated ‘Die Katakombe’ in the kilns in the basement of the tile factory. These masks were painted at the entrance. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

The prisoners recreated ‘Die Katakombe’ in the kilns in the basement of the tile factory. These masks were painted at the entrance. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

Underneath the pressing room lies a vast system of bricked tunnels and caves. These originally held the kilns used to fire the terracotta tiles. On one of the larger kilns is a painting of the two masks of the commedia dell’arte along with a painted sign reading Die Katakombe.

Here, the inmates recreated a famous Berlin cabaret of the same name that had opened in 1929, and flourished during the jazz age in the Weimar Republic. The cabaret was closed by the Nazis in 1935, but reincarnated by inmates who presumably remembered it just a few years later.

Prisoners would come down here to listen to jazz, watch performances and swap stories. One internee, Alfred Kantorowicz, wrote in his memoir, Exile In France, that “at night, the candlelight made the activities of Die Katakombe seem like opera scenes.”

Traces of those imprisoned here still adorn the wall of the camp. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

Traces of those imprisoned here still adorn the wall of the camp. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

There was even a bar that served black market Pernod liqueur, wines and cognac smuggled into the camp. You can still see rows of brick and concrete blocks arranged in the pattern of chairs surrounding a long-forgotten stage there today.

After pleading with guards and prison officials, some of the early anti-Nazi Germans held at Les Milles were allowed to escape to safety. Many left via train to the port of Marseille and then onto the United States.

Following the surrender of France in June 1940, however, the permissive nature of the camp changed. The same train wagons which transported the artists of Les Milles to safety would soon be used for a much darker purpose.

The Legionnaires living quarters; the French Foreign Legion contained many Germans who once war was declared were detained by the country they had been fighting for. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

The Legionnaires living quarters; the French Foreign Legion contained many Germans who once war was declared were detained by the country they had been fighting for. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

After the surrender, the French government was nominally still in charge, but the country was split into two parts administratively, with Germany occupying the north and east. The day-to-day running of the so-called Free Zone in the south was left to the new collaborationist French government, based in a spa town whose name would go down in infamy: Vichy.

At this point, Camp des Milles moved into the second chapter of its existence, as an internment camp for so-called “undesirables”; these included refugees, communists, political exiles, foreigners caught on French soil during the war, and increasingly, Jews. Around 200 such camps, of varying sizes, were created throughout France. Les Milles was the largest in the south and became the principal organizational center for the processing of these “undesirables.”

As more and more refugees were sent to Les Milles, conditions rapidly deteriorated. Composer Gus Ehrlich, an internee, described how “they were quartered on the third floor of the main building, which was even less suited for human habitation than the floor below.....there was hardly any straw left. Many slept on the bare floor.”

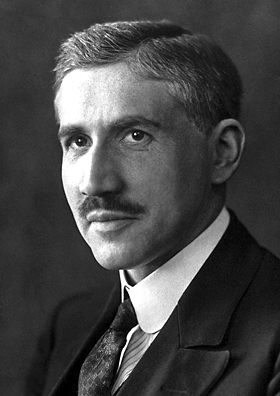

Nobel prize winner Otto Fritz Meyerhof, who was interned at Camp des Milles. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

For many at Les Milles, the great hope was to emigrate to the United States; the camp was viewed as an unpleasant but necessary inconvenience to be endured while the endless red tape was processed. But by July of 1940, exit visas to New York were no being longer granted. By this time, the population was almost solely Jewish. The number of internees surged throughout the summer, cramming into increasingly dire conditions in the camp, and levels of despair inside the camp rose.

This marked the beginning of the third and most deplorable chapter in the camp’s history. Toward the end of summer, the Vichy government began the process of handing over around 2,000 Jews to their eventual murderers. In August, the first trains came to begin the deportations to the dreaded Drancy camp on the outskirts of Paris. From there, prisoners were sent to the Auschwitz Birkenau extermination camp. And it was not the Nazis, but a high-ranking French politician, Pierre Laval, who voluntarily included all the children.

After Germany occupied all of France in 1942, the camp was closed and turned into a munitions factory. After the war, it reverted to its original purpose, making Provence’s red roof tiles, until it was finally abandoned.

The factory that produced the distinctive red tiles found on almost every roof in Provence and home one of the darkest chapters in French history. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

The factory that produced the distinctive red tiles found on almost every roof in Provence and home one of the darkest chapters in French history. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

For three decades, a dedicated group, including survivors of the Les Milles camp, fought to reclaim the old brick factory and turn it into a permanent memorial. The camp was officially opened as a place of remembrance on Sept 10, 2010.

It remains one of the few intact internment camps left in France, thanks to a 30-year struggle to have it protected. These days, Aix-en-Provence is one of France’s most popular tourist towns, a charming ancient city surrounded by rolling vineyards, fields of lavender and the Montagne Sainte-Victoire that so captivated Paul Cezanne. But few of those tourists know about Les Milles, or the museum dedicated to the horrors that happened there.

Alain Chouraqui, president of Les Milles Camp Foundation, says the museum’s aim is “not for the visitors, especially the young, to leave overwhelmed by the darkness of the persecutions, but rather that they become aware of vigilance and resistance,” according to literature at the camp.

This cartoon was just one of 300 works of art produced at the camp. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

This cartoon was just one of 300 works of art produced at the camp. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

Visiting the camp today requires you to go through airport-style high-security gates and X-ray equipment. The courtyards are patrolled by heavily armed and highly vigilant troops. Walking through the dust-covered brick factory is a poignant reminder of a chapter of French history that is largely unknown.

Across the street from the factory is the old railway station of Les Milles, where the older gentlemen of the town like to play petanque. An old black wagon still rests at the siding as a permanent reminder of what happened here. Written on the side it says the wagon can hold eight horses “or 40 men.” In Les Milles’ darkest days, wagons like this delivered thousands of men, women, and children into the hands of the Nazis.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook