The Strange Afterlife of Edgar Allan Poe’s Hair

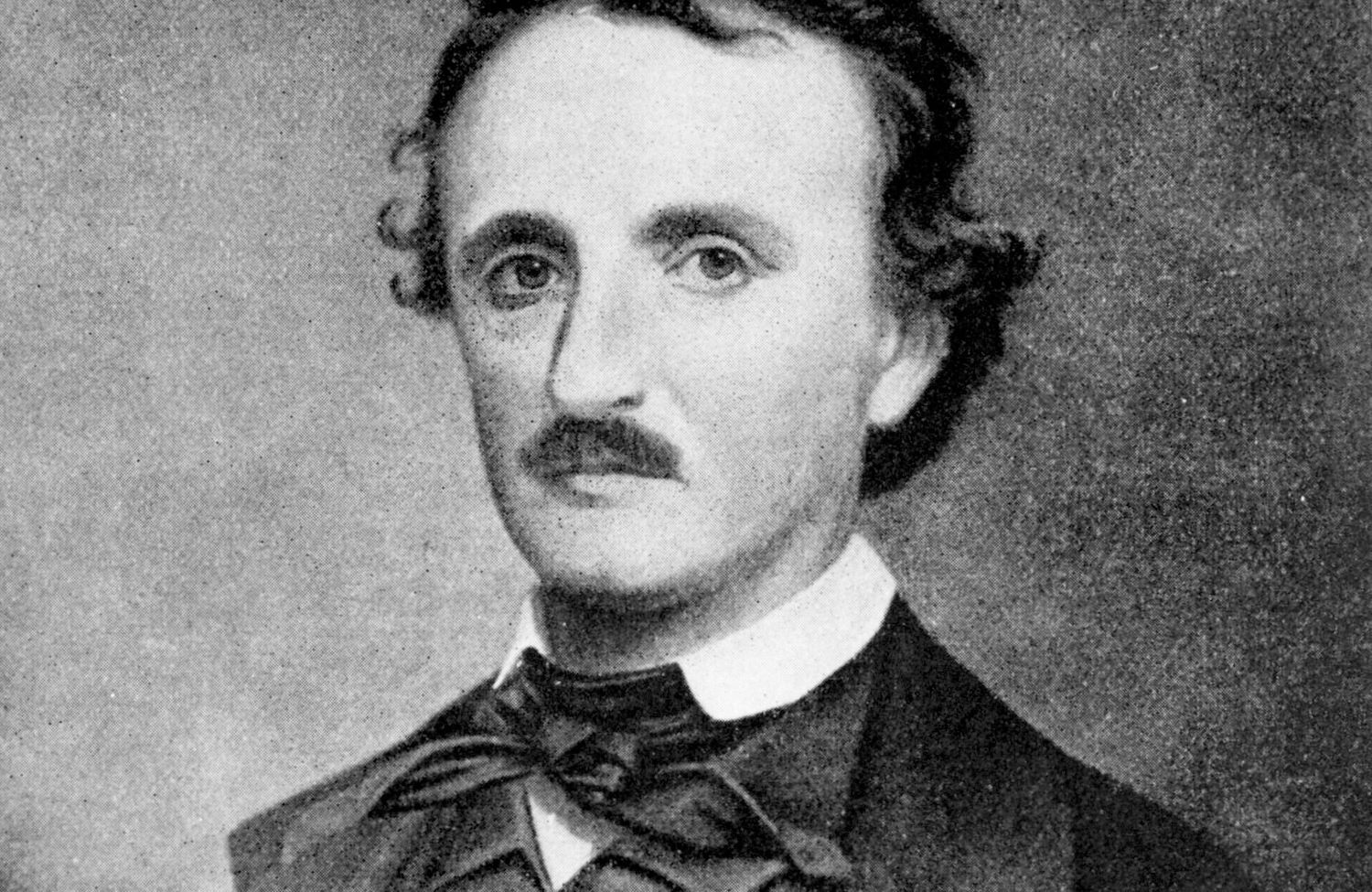

Portrait of Edgar Allan Poe, painted from a daguerreotype after his death by Oscar Halling in 1868.

Portrait of Edgar Allan Poe, painted from a daguerreotype after his death by Oscar Halling in 1868.

Nearly 30 years ago, a woman from Tennessee was clearing out her grandfather’s Baltimore house in order to sell it. She stumbled on a box containing two photographs. One was of Edgar Allan Poe, and the other was of the famous author’s estranged sister, Rosalie Mackenzie, who shared a striking physical resemblance to her brother.

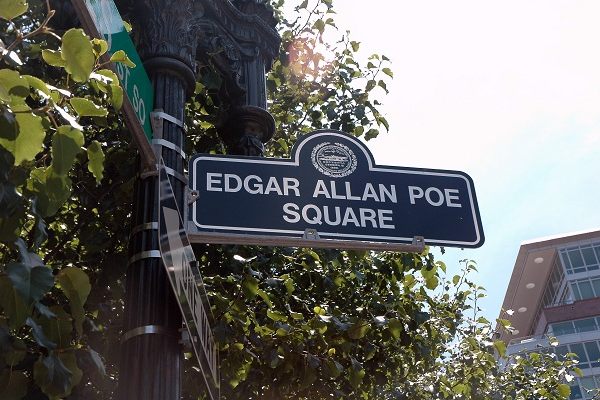

She got in touch with Jeffrey Savoye, who runs the Edgar Allan Poe Society of Baltimore, to see if he was interested in the find. He certainly was. Savoye maintains what is quite likely the Internet’s greatest repository of information on Poe. “I may have bought the whole lot for $35, sight unseen,” he recalls.

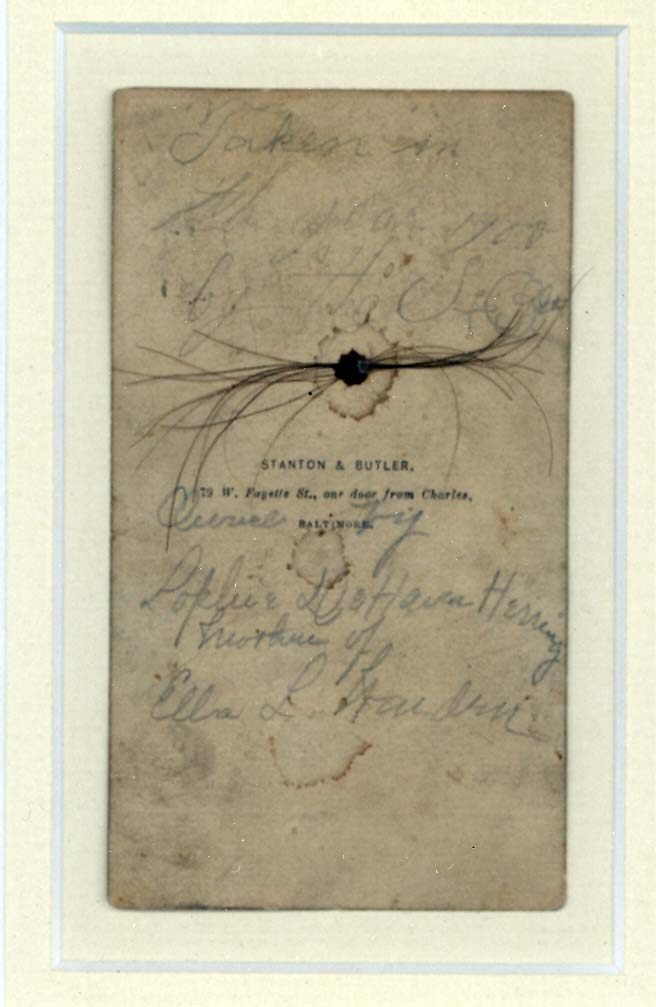

But the woman’s find was not just the photograph. On the back of the picture of Poe–a copy of a well-known Oscar Halling portrait—there was a scrawled note and approximately twelve strands of chestnut brown hair about two inches in length. The locks are held to the photo not by wax, but by an animal-based glue that Savoye suspects is made of rabbit skin.

The hair, improbably enough, turned out to be a lock taken directly from the head of Edgar Allan Poe, celebrated poet, mystery writer, and literary critic. It turns out that this Poe lock was hardly a one-of-a-kind relic—there are purported to be at least a dozen of them in collections across the country. There is no central repository, no tracking mechanism for this odd bit of history. Only a motley collection of interested parties, all of whom must have looked at stray bits of brown hair and wondered, could this really belong to Edgar Allan Poe?

The story of the hair begins on October 8, 1849, at a pre-funeral viewing for the author of The Raven, and The Tell-Tale Heart in Henry Herring’s Fell’s Point, Baltimore home. In attendance were eight people, including his cousins Neilson Poe and Elizabeth Rebecca Herring, and an acquaintance, the doctor Joseph Evans Snodgrass. Poe had passed away the day before.

During the morose event, Ms. Herring did something that was all the rage at the time: she took clippings of the dead man’s hair, most likely from the back of his head, an area obscured by the pillow.

Poe’s hair, once “dark, hyacinthine” but now brown and thinning, was an attraction in life and, now, in death. “His remains were visited by some of the first individuals of the City, many of them anxious to have a lock,” reported Poe’s attending physician. And so Herring (and perhaps others) obliged them, distributing the famous locks to various guests.

The hair found attached to a photograph in a Baltimore home. (Courtesy of Jeffrey A. Savoye)

The custom seems strange now, but it was once fairly common in the U.S. and Europe. “Throughout the nineteenth century, locks of hair were used both as memento mori to commemorate the dead and as symbols of affection for the living,” notes historian Eva Giloi, with even royalty engaging in the practice. Paul Koudounaris, author of Heavenly Bodies, says preservation of the hair is not a reminder of death, but “the creation of a personal relic.”

Originally, said Koudounaris, a relic had been “the part or possession of a person who died in a blessed state and can act as an intercessor for God.” But by the 19th century, he said, “the idea of having a relic—this personal keepsake—with quasi-magical power had spilled over into the secular world, with the desire to just keep a piece of the person around, as a touching reminder, devoid of the original sacred connotations of what a relic was.”

The custom of saving posthumous clippings was widespread, and transcended class. There was even a precedent for it within the literary world. In 1817, Jane Austen’s sister Cassandra cut off several locks of the Pride and Prejudice author’s light brown hair as she lay in her coffin. She intended to keep them as mementos.

In Poe’s case, his hair was even given as a gift during his lifetime. In 1846, a fan requested the writer’s autograph, but he decided to offer her some of his hair instead. “I guess I do want a lock of Mr. Poe’s hair!” she replied, “but I also want a line of his writing.” (There’s no record how Poe’s hair was clipped, but scissors were the likely implement of removal. In The Murders in the Rue Morgue, Poe wrote of the “great force necessary in tearing thus from the head even twenty or thirty hairs together.”)

The enthusiasm for Poe’s hair has hardly abated among collectors and Poe obsessives. In fact, celebrity hair—despite a considerable ick factor—still seems to be sought after. “Clippings from long-dead celebrities’ hair have emerged widely at auctions in recent years,” observed the New York Times. Indeed, it wasn’t so long ago that Susan Jaffe Tane, owner of the world’s greatest private Poe collection, purchased a lock of the author’s hair—as well as his fiancée’s engagement ring, photographic portraits, and other paraphernalia—for a reported $96,000. Poe’s tresses have also been sold on eBay.

In the 166 years since his death, locks attributed to Poe have turned up in a number of places and collections, private and public. How they got there is a fascinating window into Poe’s circle of friends and family, his acquaintances, and others who simply wanted a piece—an actual remnant!—of the renowned writer. In some cases, the hair can be traced directly back to the wake.

Take, for example, the lock that resides in the Edgar Allan Poe Museum in Richmond, Virginia.James Howard Whitty, editor of The Complete Works of Edgar Allan Poe and founder of the museum, purchased about a dozen strands at auction. The provenance isn’t definitive–which is true for most of the Poe hair in circulation–but Whitty acquired it no later than 1922, the year it entered the museum’s collection.

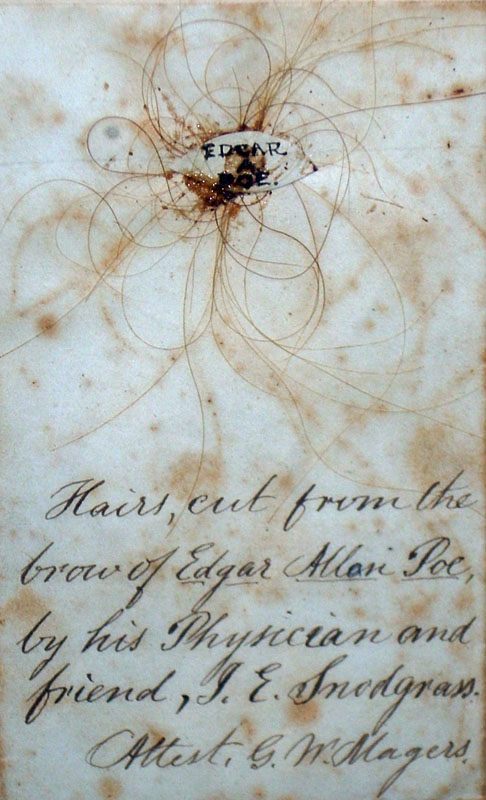

The protein filament curio came courtesy of Dr. Joseph Evans Snodgrass, one of the last men to see Poe alive. Snodgrass was summoned by an employee of the Baltimore Sun, who found a delirious Poe in the gutter outside Gunner’s Hall, a local bar and pop-up polling place. Days later, Snodgrass clipped Poe’s hair and, according to the museum, “gave the souvenir to G. W. Magers, in whose handwriting it is authenticated.”

The lock clipped by Dr. Snodgrass. (Photo courtesy of Chris Semtner, Poe Museum)

According to Christopher Semtner, a curator at the Poe Museum, Magers was “a Baltimore publisher active in the 1840s through 1860s. I have found some books published under his name during that time. I have also found some of his poetry online. I also found a letter he wrote to the editor of Scientific American in 1887.”

Snodgress, however, was not the most reliable of sources. His hobbyhorse was temperance (when he gave an account of Poe’s death, it was to the Woman’s Temperance Paper) and he happily attributed Poe’s early demise at 40 to alcoholism, claiming he’d smelled booze on the dying man’s breath. This wasn’t true. “Samples of Poe’s hair from after his death show low levels of lead,” reported The Smithsonian last year, “which is an indication that Poe remained faithful to his vow of sobriety up until his demise.”

In any case, there is little about these events of which one can be certain. The authenticating letter, written by Magers—based on the account of Snodgrass—should be viewed with skepticism. “People keep embellishing their account, as time goes on,” says Semtner.

Snodgrass would’ve given the hair to Magers no later than 1880; the good doctor died that May.

Later, the hair clipped in Baltimore in the mid-19th century ended up in the possession of George Smith, a major rare book dealer in New York. The founder of the Poe Museum in Virginia likely purchased it sometime during the first quarter of the 20th century.

What, exactly, gave rise to the posthumous hair clipping trend? One factor, says Colin Dickey, author of Cranioklepty: Grave Robbing and the Search for Genius, was the change in attitude regarding the treatment of corpses. Whereas it had once been acceptable to keep the dead in the home for long periods, by the early 1800s, medical authorities realized this was deeply unsanitary and led to the spread of diseases.

Instead of burying family members in the backyard, where they could be visited—as was customary—people were now required to bury bodies in cemeteries well outside the city. These policies meant that people could no longer lay out the dead on their living room table. A new way for memorializing the dead had to be embraced.

People saved hair prior to the 19th century, but the interest in sanitation—and the attendant lack of accessibility to the body—gave the practice a new urgency. As it happens, the period of Poe’s fame coincides with the peak of hair clippings used as relics. It would not fade away until the end of the century, as a result of another cultural shift, to a less ostentatious culture of mourning. By the 20th century, there were other ways to commemorate people, including photography. “The physical remains,” says Dickey, “became less important.”

Yet for his relative Mary Herring, Poe’s hair was of paramount importance.The lock she gave to her daughter, Ella Warden, has been housed in the Baltimore’s Enoch Pratt Free Library since the mid-1930s. A letter from Ms. Warden to “Miss Evans” of the Poe Society, dated November 11, 1936, notes a gift of two “trinkets,” along with some other personal items, including a smelling salts bottle. In her missive, Warden stressed that the thick locks were cut by her mother as Poe’s “body was lying in his coffin in my Grandfather Herring’s house, from which Poe was buried, and not from the hospital, as is commonly believed.”

They belonged to Virginia Clemm, Poe’s wife and, also famously, his cousin. She in turn gave them to Mrs. James Warden (née Mary Herring), who thought the tresses would be safer in the library, and signed off on a long-term loan. The Pratt Library now keeps the hair in a secure vault. It’s a seasonally popular item, attracting visitors in the fall and around Poe’s birthday, in January.

The 79-year-old Ella Warden letter gives the Pratt’s lock a fairly strong provenance—a paper trail, more or less, so a buyer understands how an item came to be in the possession of a seller. Sometimes, in lieu of a physical document, other modes of authentication are required.

John Reznikoff, who identifies himself as “a treasure hunter,” owns some 150 historic hair relics, including locks from George Washington, John F. Kennedy, and Napoleon. “I just found a terrific lock of Jimi Hendrix hair,” he says.

Reznikoff’s piece of Poe hair, which came in a gold locket, was purchased in 2008 from a dealer, via a Chicago insurance agent—he declined to name him—who had bought a toolbox for $150 from a maintenance man in his office. “Upon purchasing the toolbox and bringing it home,” wrote the agent to the dealer, “I found within a small plastic box … along with a very brown and brittle piece of paper with a printed paragraph or two referencing the item. The paper literally crumbled in my hands.”

The locket containing strands of Poe’s hair. (Photo courtesy of Katharine Chandler, Philadelphia Free Library)

Inside the locket is written:

Edgar A. Poe

Born Jan 19th 1811

Died Oct 7th 1849

This is in error. Edgar was born in 1809. He often claimed to be a couple of years younger than he really was, to appear more precocious.

The other side of the locket is inscribed with:

Virginia E. Poe

Born Aug 13th 1822

Died Jan 30th 1847

This, too, is in error. Virginia was born on August 15th.

Reznikoff doesn’t doubt its authenticity. He points out the engraving is consistent with the period, and the hair is the right shade. “This was purchased very innocently, and not for a lot of money,” he says. “And you know what these things are worth.” He puts the value of the locket and hair at $500,000.

The number of Poe locks in private collections is very small, and the few collectors are certainly aware of each other. “I have the motherlode,” Susan Jaffe Tane declares, and it’s largely in her apartment in the Upper East Side of Manhattan. Much of her Poe memorabilia is kept in a custom-made paisley box about the size of a dictionary. The hair is in a small folder in a plastic pouch, bound with ribbon into marbled board.

The authenticating document is an undated letter from the granddaughter of Elizabeth Herring. Tane purchased the family letters, the hair, an engagement ring, a silver spoon, and photographs of Poe and his relatives in December 2012 for a rumored $96,000. “I’d already had a piece of his coffin, so I knew the hair was out there,” she said. “But it’s not the sort of thing that you’re interested in until it falls in your lap.”

The other items hold more appeal for her. “There’s nothing about the hair that I like,” she admits. “It’s just another piece of the physical entity.” She has exhibited them, however, since “unless someone’s got his teeth,” the locks are very likely all that’s left of the author’s corporal body.

Is there a line she wouldn’t cross? Would she buy Poe’s teeth, for instance? “I’m not sure I would draw the line,” she says. Asked if there is a Poe-related acquisition she might consider distasteful, she answers, “I would’ve said the coffin, but I bought it for an exhibition.”

Generally speaking, nailing down the source of hair is problematic. For one, it’s “too easily faked. You can cut off a piece of hair and say it’s so and so’s. And who’s to say not?” says New York Public Library curator Isaac Gewirtz. “I would never purchase hair. It has no research value,” he says. “One doesn’t learn anything about the author of a lock of hair.”

So is all this hair really from Edgar Allen Poe’s head? Hard to say. DNA testing is possible for historic hair, but it’s unlikely to be done well in the case of Poe, given the age of the hair and probable level of contamination. Testing is also limited because hair that is clipped—as opposed to yanked—doesn’t contain nuclear DNA, which resides in the root. Lastly, Poe had no children, so there are no direct descendants who might give comparative hair samples. (Realistically, it’s probably not in the interest of the owners to scientifically authenticate the hair; the procedure is expensive and, given the acceptable, relatively loose standard of provenance, there’s no real upside.) Occasionally, however, celebrated old hair gets put under the microscope. Back in the 1990s, Beethoven’s locks were analyzed to determine his cause of death.

On a brighter note: not all of Poe’s hair was removed posthumously. A lock in the collection of the Indiana University’s Lilly Library is one of the few we know for certain was not taken at the wake. It was acquired by the pharmaceutical industrialist Josiah Kirby Lilly, Jr., for whom, says librarian Rebecca Baumann, Poe was an “early collecting obsession.”

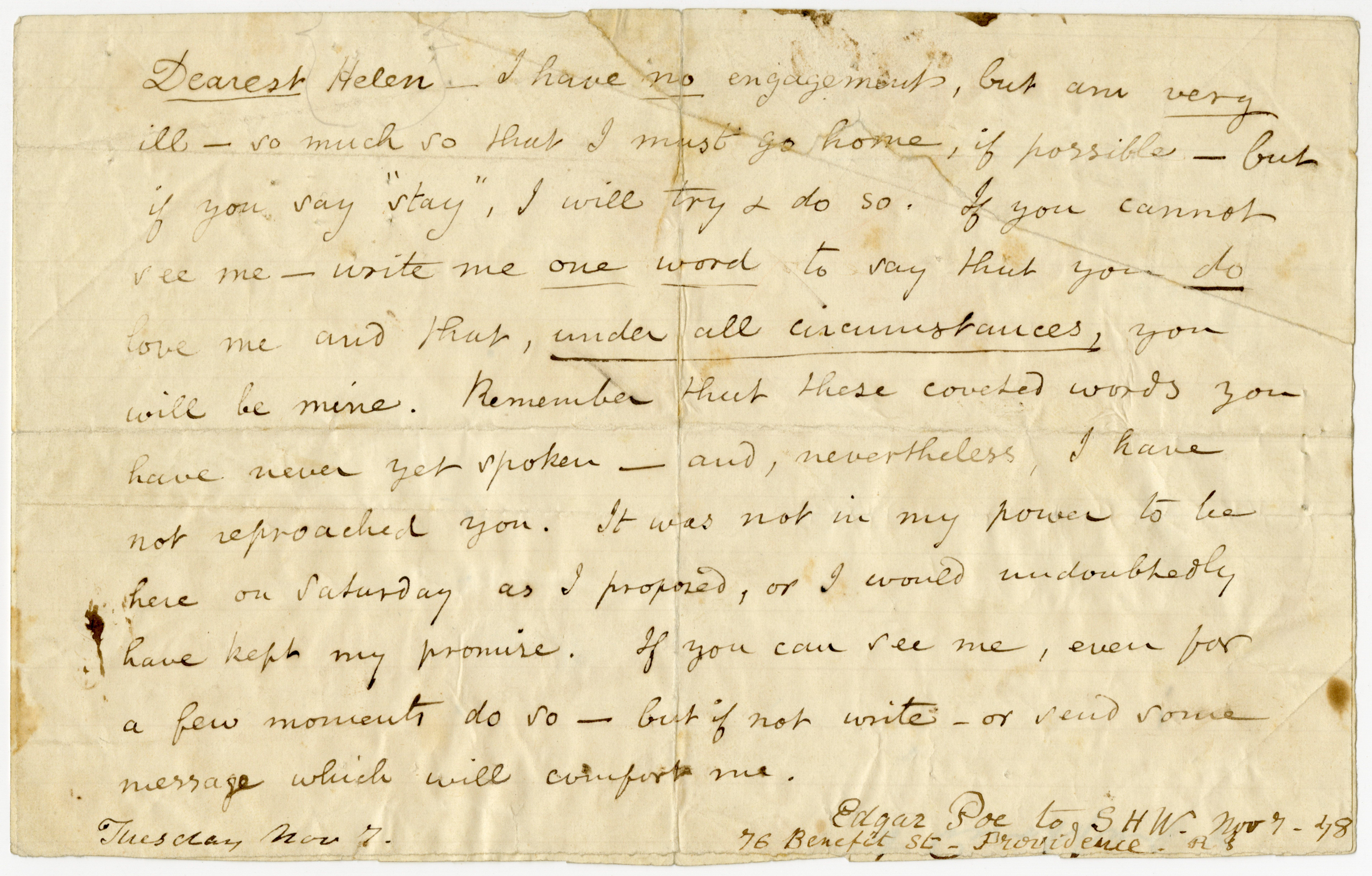

Poe’s dramatic letter to his one-time fiancee, Sarah Helen Whitman. (Courtesy of the Lilly Library, Indiana University)

One chestnut-colored curl in Indiana, purchased from Max Harzof, a famed New York bookseller, was found in a black tin box of letters that Poe wrote to his one-time fiancee Sarah Helen Whitman. Upon the envelope was written: Mrs. Sarah Helen Whitman / Providence / RI / Sent to me on the evening / of Nov 8th 1848.

“Sarah Helen Whitman, a sort of 19th-century version of the modern ‘Goth’ girl, was known for wearing black clothes and a coffin-shaped charm, holding séances at her house, and writing transcendentalist poetry,” Baumann emailed. “She was briefly engaged to Poe until she received an anonymous note at the library claiming that he had returned to drink (which he had sworn off of as a condition of their engagement).”

Their courtship, wrote author David Randall, was “brief and violent … during which both parties were often alternately or jointly hysterical.” In a letter dated November 7, Poe wrote to his beloved: “If you cannot see me—write me one word to say that you do love me and that, under all circumstances, you will be mine. Remember that these coveted words you have never yet spoken—and, nevertheless, I have not reproached you.”

There’s a second lock in the Lilly collection, this one sent in 1849 to Annie Richmond, a friend of Poe’s, by Maria Clemm (mother of Virginia). The hair is encased in a pearl-ringed brooch, which maybe from the writer’s deathbed. “That is certainly the library lore of the item, but I was unable to find anything to conclusively establish this,” says Baumann. “The date is right, and it certainly fits in with the custom of funeral jewelry, but I haven’t been able to confirm.”

The sheer quantity of Poe hair dispersed across the country is remarkable. No less than four libraries along the Eastern seaboard have their own caches: In addition to the collection in Baltimore, the New York Public Library has a lock of his hair, acquired in 1938, while the Philadelphia Free Library is home to a strange miniature of Poe, painted on ivory, that also contains some of his prized hair. Given this fact, one wonders how much hair still remained when Edgar Allan Poe was buried.

Poe was initially entombed in an unmarked grave in a Baltimore cemetery. It was neglected terribly. A decade after Poe’s death, Maria Clemm wrote to Neilson Poe, “A lady called on me a short time ago from Baltimore. She said she had visited my darling Eddie’s grave. She said it was in the basement of the church, covered with rubbish and coal. Is this true?”

By 1875, however, the author’s reputation had been resuscitated and burnished, and Poe’s body was exhumed and reburied in a more tourist-friendly part of the cemetery. A reporter for the Baltimore American was there when the coffin was first re-opened, where it was inspected by a small gaggle of curious onlookers. According to him, the skeleton was “almost in perfect condition, and lying with the long bony hands reposing one upon the other,” while the skull had “some little hair…still clinging near the forehead.”

There’s something poignant about it. Even as the rest of Poe’s body had fallen away—neither carefully cut up like the old man in The Tell-Tale Heart nor encased in a catacomb like the nobleman in The Cask of Amontillado—his remaining locks had hung on.

A pearl-ringed brooch with Poe’s hair inside, perhaps from the author’s deathbed. (Courtesy of the Lilly Library, Indiana University)

Update, 5/12: An earlier version of the story misstated the century of Poe’s life—it was the 19th century, not the 18th. We regret the error.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook