The Strange, Centuries-Old Tradition of Stuffing Dead Horses

Most taxidermied horses are of the battle-hardened variety.

Many a hunter has taken one of their big catches—a 12-point buck, for example, or maybe a moose—to a taxidermist, but not so long ago, you may have also considered taking a different animal: your beloved, recently-deceased horse.

Stuffed horses might not be as common as they used to be (many a general saw their war horses fit for stuffing), yet you can still find them, living on in perpetuity in a collector’s home or perched in a museum, staring at you, waiting to be stared back at.

Take movie cowboy Roy Rogers, who had both his horse Trigger, who died in 1965, and Dale Evans’ horse Buttermilk, stuffed for display. Trigger was positioned rearing, the way he used to with Rogers aboard, his front legs gently pawing the air. Buttermilk was mounted in a more serene pose, with all four hooves on the ground. When the Roy Rogers museum in Branson, Missouri, closed, the horse sold at auction for $266,000, USA Today reported. The high bidder was Patrick Gottsch, who owns the cable channel RFD-TV. He bought Rogers’ stuffed German shepherd, Bullet, too.

Dig a little deeper, and, even within the already-uncanny world of stuffed animals, you’ll find that taxidermied horses occupy an even stranger category. They’re not hunting trophies, of course, but domestic animals, which means people don’t usually see their first horse just because someone preserved one. And they are very big, meaning that stuffing one is no small matter, unlike a Victorian’s favorite hound or kitten. (Sometimes, though, people do have just the horse’s head and shoulders mounted.) What’s not so surprising, then, is that when they’re displayed, the horses attract attention.

On Chincoteague Island in Virginia, for example, famous equine residents Misty and her daughter, Stormy, are on display in the Beebe Ranch museum, there to commemorate the inspiration for Marguerite Henry’s novel that helped make the island and its ponies famous, 1947’s Misty of Chincoteague. Today, visitors come for both the herds of wild ponies on nearby Assateague, as well as the stuffed ones in the museum.

Most stuffed horses, though, are of the battle-hardened variety, warhorses cherished for their survival skills, their loyalty, or merely just for good luck.

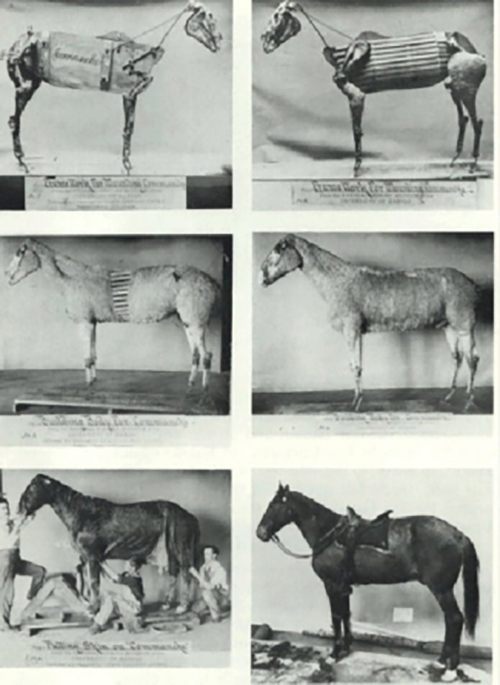

Take Comanche, the horse who was reputed to be the last survivor of the Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876. Comanche is currently displayed at the University of Kansas’ Natural History Museum. His body is saddled and bridled, and he appears to look off into the distance. Another cavalry horse, Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson’s Little Sorrel, is at the Virginia Military Institute. After the war, he spent years touring around, especially throughout the South. Little Sorrel is untacked, and poses with a defiant tilt to his chin. His saddle is in a case nearby. (Robert E. Lee’s horse, Traveller, was preserved as a skeleton, but is now buried.)

Civil War Union general Phil Sheridan’s horse, Rienzi, stands in a case at the Smithsonian, in the National Museum of American History. (The Smithsonian also has a horse hoof that belonged to a heroic fire horse who galloped to a fire on a bloody stump, having lost his foot in an accident on the way.) In 1864, Sheridan, aboard Rienzi, galloped 15 miles from Cedar Creek to Winchester, Virginia, rallying his troops and helping repulse Confederate soldiers.

Thomas Buchanan wrote a poem about the ride: “Be it said, in letters both bold and bright/Here is the steed that saved the day/By carrying Sheridan into the fight/From Winchester–twenty miles away!” After the war, Sheridan kept Rienzi, who was later renamed Winchester. The horse grazed peacefully through his old age, died in 1878, and then Sheridan had him mounted.

At Mount Vernon, a diorama features a George Washington mannequin aboard a taxidermied horse, a substitute for Blueskin, Washington’s favorite warhorse, and the big gray who is seen in portrait in many Washington scenes at Valley Forge, including Arnold Friberg’s 1975 painting of the general kneeling in the snow, Blueskin at his side. The taxidermist told the Washington Post in 2008 that the substitute horse was in fact an Amish workhorse who died with his thick winter coat, found after he’d put out a call looking for a recently-dead white horse.

The Blueskin stand-in reveals that, original or not, taxidermy allows us to see nature in a specific way. Or, as the academic John Herron has written, “As a blend of natural science and environmental representation, taxidermy situates the natural world within a human context, and through these posed animals we can make connections between biological processes and our understanding of the human ideal.”

Or maybe we just want stuffed creatures there for their novelty.

Consider General, a horse that is not very famous, save for one thing: General is said to be the one of the heaviest horses that ever lived, according to the West Virginia State Farm museum, where General stands, stuffed and on display. He weighed 2,850 pounds, and is positioned today not in a case but in a little corral, looking out at visitors, his own kind of celebrity.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook