The 10 Trials of the Master Bladesmith

Master bladesmith Tim Hancock forges a Damascus steel blade, is a badass. (Image: Daviddarom/Wikipedia)

You think it’s hard to get a job in your industry? Try becoming a master bladesmith—there are fewer than 200 in the world.

Joining this elite class of swordsperson requires accreditation by the American Bladesmith Society, one of the largest bladesmith organizations in the world. The road from knife hobbyist to professional metalworker is long, filled with incredibly rigorous tests of both material knowledge and physical dexterity. You learn to be an apprentice, and then, later to have an apprentice. You cut steel, you cut hair, you ruin knives.

In other words, it takes more than just being sharp to get an edge in the ancient art of bladesmithing (you’re welcome).

To find out just what is takes to earn the title of master, we spoke with Harvey Dean, a master bladesmith and chairman of the American Bladesmith Society (ABS). The society itself is rather young, having been started in 1973 as a reaction to the dwindling number of bladesmiths crafting quality blades. Many practitioners of the craft had moved away from solid pattern welded construction (which forms a blade out of multiple pieces of metal forged together), opting to practice the quicker and cheaper process of stock removal blademaking (simply cutting the pattern of the blade out of a piece of metal and sharpening it). The founder of the ABS, William Moran, introduced his incredibly strong “Damascus steel”—created by forming a composite metal rod (or “billet”), pounding it flat, and folding it over itself again and again—at a trade show in 1973. He even handed out pamphlets about making Damascus steel to awestruck convention-goers in order to spread around his technique. This form of metal has been the gold standard for the ABS ever since.

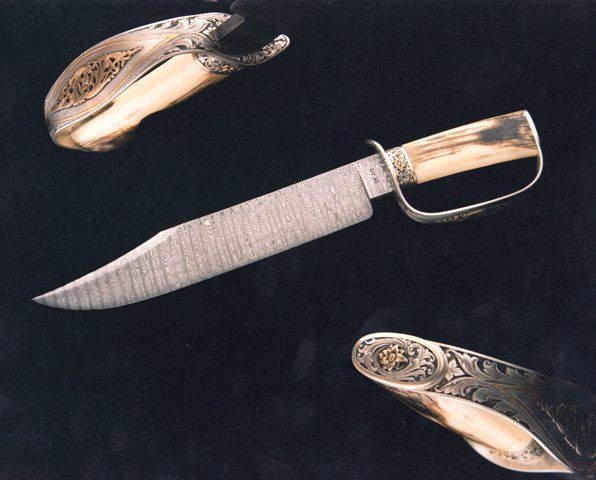

One of Harvey Dean’s Damascus steel bowie knives, showing the distinctive ripples of the hundreds of folds. (Image: Harvey Dean/Used with Permission)

Dean has been making blades for more than 20 years, having earned his master rating in 1992. He has administered a number of master and journeyman tests over the years and even teaches potential bladesmiths on the ins and out of the craft. But to begin, one simply has to sign up with the ABS and start making blades. From the time time you sign up with the ABS you are considered an apprentice. “Now that doesn’t mean you have to be working under somebody,” Dean says. “That’s just your title. You’re kinda left on your own to find your education, although we do offer some classes and seminars to help you along.” Journeyman and master bladesmiths are generally more than willing to help pass along their knowledge and techniques, but it is up to the aspiring bladesmith to seek out their wisdom.

Once you’ve been a member of the ABS for three years (only two if you also take their “Introduction to Bladesmithing” course), you can take your skills to the next level by finding a master smith to give you a journeyman test. Hopefully you’ve been using your years as an apprentice practicing and learning from your peers, because the test is no walk in the park.

To achieve journeyman status, an apprentice must forge a simple carbon steel blade—no Damascus steel or fancy patterning, not even the hilt needs to be anything fancy. The blade itself can be no longer than 10 inches, and it had better be pretty sharp. You can bring this blade to any Master Smith willing to oversee the test. Given how small the master bladesmith crowd is, it will probably be someone you already know. “I know a lot of the people that come and test [at my shop],” Dean says. “I give them a little speech right at first, saying ‘I know we know each other, and we’re friends, but as soon as you tell me you are ready to take this test, our friendship ceases for a little while. Because it has no bearing on the test whatsoever. Either you pass or you fail.’” There is no room for nepotism in the world of blademaking.

Another of Dean’s signature bowie knives. (Image: Harvey Dean/Used with Permission)

The first test requires nothing more than cutting a rope. However, this must be an unanchored, free-hanging length of rope, and the cut must be made in a single swipe, chopping off approximately six inches from the bottom of the rope. This tests the geometry, shape, and sharpness of the blade. Most applicants swing at the rope in a diagonally downward slice to get a better cut, since coming at it horizontally is more likely to cause the rope to wrap around the blade instead of slicing through.

Assuming the rope is cut successfully, the apprentice must move on to the second phase of the test: chopping wood. In this deceptively simple test, you’ll chop through two regular, construction-grade 2x4s. This often requires a number of consecutive whacks, digging out triangular chunks from the wood, until the boards are scored enough to break. It is violent work that is meant to see how well the blade holds its edge. Any nicks, chips, rolls, or other deformations in the blade’s edge can result in failure. The Master will sometimes run their fingernail down the blade to detect any imperfections invisible to the eye.

The next step in the test involves cutting a much softer target: hair. To demonstrate that the edge of the blade didn’t dull while chopping wood, the apprentice has to shave some hair off his or her own arm. (You can shave something else, but they probably prefer you to keep it clean.) According to the official testing guidelines, “Enough hair must be shaved to demonstrate that the edge remains keen and shaving sharp.”

The final step in the test is the most stressful—literally. During the final phase of testing, the tester will place the tip of the blade in a vise, and bend it to a 90 degree angle, sometimes using a pipe for leverage. This tests the strength of the metal and the apprentice’s ability to heat treat it, giving the blade a harder edge and springier back. If the stress on the blade causes it to chip, shatter, or snap, the apprentice fails. A slight bit of cracking is allowed, but this is a slim margin for error.

No matter the outcome, the knife is ruined.

It may seem a bit tragic to destroy a knife immediately after proving its superior quality, but as Dean says, “If a guy’s going to really get serious about it and wants to make sure he passes, he’s gonna have to destroy some before he gets to a master smith’s shop.” If the apprentice does pass the performance tests, he or she must then brave the judgement of a select jury of peers that only convenes twice a year, at either the Blade Show in Atlanta, Georgia, or the International Custom Cutlery Expo in Kansas City, Missouri.

During these panels, each apprentice must bring five carbon steel blades to be judged. Here a jury of ABS master smiths judges the five blades on exacting criteria like design, blade construction, guard construction, balance, and proportions. These blades can be much fancier, since they aren’t going to be destroyed.

If the panel deems the offerings to be of sufficient make and quality, the apprentice is finally named journeyman, and given a “JS” stamp for future blades. Now on to master.

The path from journeyman to master is essentially the same as the path from apprentice to journeyman, but you’ll also have to train apprentices under you. As a journeyman, you must put another 2-3 years of experience under your belt before applying to test for your master rank. When you do, you must then once again seek out a master to perform the test.

To become a master, the performance tests are the same, but the blade must be different. During the master performance test, a journeyman needs to make a Damascus steel blade that has been folded at least 300 times. Dean tests this with his master’s eye: “I could sit down under a microscope and count out those layers, but I can look at it and pretty much tell.” The other difference is that the blade must have a “hidden tang.” The tang is the portion of the blade hidden beneath the handle. For a full tang, the handle material is flush with the edges of the tang, the flat edge of which is usually exposed, sandwiched between the pieces of the grip. The more challenging hidden tang is fully surrounded by the handle. These differences aside, the blade must still cut rope, wood, and hair before being bent into oblivion.

A folding bowie knife by Harvey Dean that he says was one of the most challenging blades he ever created. (Image: Harvey Dean/Used with Permission)

Once again, the journeyman must then take five blades in front of a jury of masters, at least one of which must be made of Damascus steel. This time, one of those blades has to be a Damascus steel quillion dagger. Quillion daggers are a medieval European style of knife that has a crossguard across the hilt. They are usually of elaborate make, marking the sign of a true master. “It’s one of the harder knives to build. Probably every [technique] you’re ever going to use in any kind of knife is going to be in that,” Dean says. “Ever since the jurying [portion of the certification] has been done, it’s required a quillion dagger. It’s got a lot of different stuff that you normally wouldn’t use if you made hunting knives, or bowie knives, or pocket knives.”

If the quillion dagger and the other juried blades pass muster, the journeyman is named a master smith, and given an “MS” stamp to mark future blades as the work of a master.

Even though the number of official bladesmiths is small, the designation is not going away. Dean says that many of the people who seek to become master bladesmiths come from all walks of life. Some are looking for professional title, while others just consider bladesmithing a hobby. Most people aren’t making massive swords or fantasy blades, but drop point skinning knives, folding pocket knives, and, increasingly, culinary blades are popular constructions.

Dean says that the ABS now has around 1,300 registered members, hailing from 23 different countries. As one of the only bladesmithing organizations left in the world that gives out official ratings, they are seeing an increasingly international membership, to the point that Dean says they are even considering changing the name of the organization to be more inclusive. The title of master bladesmith is not impossible to achieve, but you’d better be on point.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook