The Unknown French Horticulturist Who Made Lilacs Happen

If you’ve ever enjoyed a stroll through a modern garden, thank Victor Lemoine.

Syringa vulgaris, one of the earliest lilacs with which Victor Lemoine worked. (Photo: Marisa DeMeglio/CC BY 2.0)

Syringa vulgaris, one of the earliest lilacs with which Victor Lemoine worked. (Photo: Marisa DeMeglio/CC BY 2.0)What started as one French horticulturist’s escape from the dreariness and destruction of the Franco-Prussian War soon blossomed into a full-scale floral revolution.

Hydrangeas, geraniums, lilacs—the varieties of flowers in the modern garden are nearly endless, but it’s hard to imagine where bloom lovers everywhere would be without the singular contributions of 19th-century hybridizer Victor Lemoine.

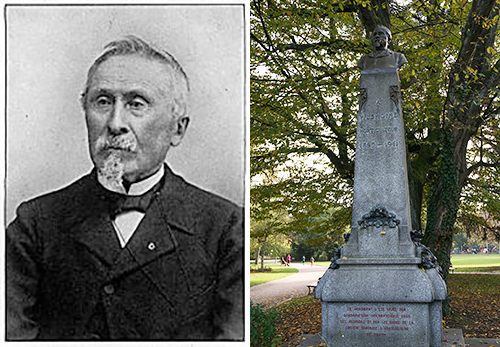

Lemoine, with the help of his wife, son, and grandson, is responsible for introducing the world to more than 200 varieties of lilacs, the popular ornamental flower known for its sweet fragrance, among countless other flower varieties. He’s considered a horticultural hero.

“There is hardly a garden today that does not have at least one plant that can be traced to his genius in horticulture,” contends lilac breeder John L. Fiala, author of Lilacs: A Gardener’s Encyclopedia.

Those who remember Lemoine, especially those writing in the wake of his death in 1911, cite his keen understanding of plant genetics and the impressive patience and work ethic that helped him to become such a prolific hybridizer.

But despite his many achievements, he was little-known even at the apex of his career. Six years after his death at the age of 89, the May 1917 edition of The Garden Magazine asked, “How many people to-day even have a ghost of an idea of the debt of reverence due to the memory of this transcendent genius?”

Born in October 1823 in Delme, in the French region of Lorraine, Lemoine came from a family with a rich history of gardening—both his father and grandfather had managed gardens at a large estate. Lemoine began his horticultural career after he left university in Vic-sur-Seille, traveling around Europe to established nurseries, like Louis Van Houtte’s in Ghent, to study the art of the masters he would one day supersede.

The nursery of Louis Van Houtte, a mentor of Lemoine based in Belgium. (Photo: Public Domain)

The nursery of Louis Van Houtte, a mentor of Lemoine based in Belgium. (Photo: Public Domain)Mastering the art of hybridization, or creating new plant varieties from preexisting ones, required meticulous attention to detail and coordination. Horticulturists would take the pollen from the anther, the pollen-producing part of the stamen, the flower’s male sex organ, and brush it onto the stigma, the head of the female sex organ called the pistil. The looming threat of a flower’s accidental self-pollination and the difficulty of controlling for environmental factors, for example, made for significant challenges for horticulturists like Lemoine.

But his fondness for flora was strong enough that in 1849 he opened his own nursery in the Rue de l’Hospice, in the northeastern French town of Nancy. The first mention of Lemoine’s work appeared a few years later, in 1852, when his double-flowered Portulaca was included in the Revue Horticole.

A garden in Nancy, France, which has a rich horticultural tradition and was the home of Lemoine’s first nursery. (Photo: Patrick Nouhailler/CC BY-SA 2.0)

A garden in Nancy, France, which has a rich horticultural tradition and was the home of Lemoine’s first nursery. (Photo: Patrick Nouhailler/CC BY-SA 2.0)Lemoine didn’t keep the most meticulous records, however, and horticulturists around the world speculate about which varieties he introduced at different points in time.

What they mostly agree on, among other things, is that in 1854 came the first genuine double-flowered Potentilla, a bold red-orange variety that he called “Gloire de Nancy,” and the first hybrids of Streptocarpus. He introduced the first double-flowered geranium, a rosy scarlet variety, in 1866, and the early 1870s saw his first double tuberous Begonia (according to Garden Magazine, “without Lemoine the Begonia would probably never have ‘arrived.’”)

But Lemoine is most remembered for his affinity for the lilac. In 1870, Fiala writes, as a distraction from the turmoil and distress that accompanied Nancy’s military occupation in the ongoing Franco-Prussian War, the 46-year-old hybridizer began what would become his greatest experiment.

The common lilac Syringa vulgaris, known for being one of the main plants Lemoine hybridized. (Photo: Joan Simon/CC BY-SA 2.0)

The common lilac Syringa vulgaris, known for being one of the main plants Lemoine hybridized. (Photo: Joan Simon/CC BY-SA 2.0)Lemoine, with his wife and his son Émile, began his work with a variety of common lilac known as Azurea Plena, a bluish and seemingly insignificant double-flowered lilac discovered in a Belgian nursery in the early 1840s.

Lemoine had an Azurea Plena bush in his garden and set out to hybridize it with single-flowered Syringa vulgaris varieties. The only problem was that working with the pesky Azurea Plena proved to be a challenge, as many of the florets had no stamens and the pistils were often twisted and deformed. And with his worsening eyesight and unstable hands, delicate cross-pollination was no walk in the park.

But Lemoine’s younger wife Marie Louise, equipped with a needle, scissors, tweezers and a paintbrush, took on much of the work atop her stepladder, wrenching open the flowers to dust the pistils with pollen from single varieties of the Syringa vulgaris strain, and then with that from the native Chinese species Syringa oblata.

Soon the number of lilac varieties he and Marie Louise had hybridized from a mere seven seeds in the first year had swelled, with around 70 cultivars introduced before 1900. Some estimates place the final number of cultivars he introduced—or helped his son and grandson introduce—at 214, known today as the French hybrids.

But lilacs weren’t his only lovechild. “During the last fifteen years of his life he devoted his energies to the improvement on Deutzias, Peonies, Hydrangeas, Weigelas, Gladiolus, Astilbes, Lilacs, Delphiniums, Pyrethrums, Heucheras, and Penstemons,” the article in Garden Magazine reports.

Weigelas, which Lemoine hybridized for the first time in 1868. (Photo: Andy/Andrew Fogg/CC BY-SA 2.0)

Weigelas, which Lemoine hybridized for the first time in 1868. (Photo: Andy/Andrew Fogg/CC BY-SA 2.0)He also worked with Montbretias, Dahlias, Saxifrages, Chrysanthemums, Bush Honeysuckles, Spiraeas, and Phloxes, according to Garden Magazine, “the results of which we all enjoy the year round.”

Lemoine’s work didn’t go unnoticed. He became the first foreigner to receive the Victorian Medal of Horticulture of the Royal Horticultural Society in London, and weeks before his death, in 1911, the Massachusetts Horticultural Society granted him the George R. White Medal of Honor.

Syringa vulgaris at the New York Botanical Garden. (Photo: Ryan Somma/CC BY 2.0)

Syringa vulgaris at the New York Botanical Garden. (Photo: Ryan Somma/CC BY 2.0)Lemoine’s lilacs can be found around the world at botanical gardens such as Lilacia Park in Lombard, Illinois, and the New York Botanical Garden. But chances are if you’re a horticultural hobbyist, the legacy of Lemoine lives right in your own garden.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook