The Video Game That Promised to Contain 52 Video Games And Failed Miserably

Action 52 wasn’t great.

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

Let’s say you had a terrible idea. It’s not an uncommon thing; we all have them daily.

And, indeed, if you look around, they’re a dime-a-dozen, from this novelty bath mat that has what look like bloody footprints on it to many people who have tried to market and sell water specifically for dogs.

But of all of the bad ideas in the world, consider what might be the worst idea of them all: A video game concept called Action 52.

The nice thing about video games is that, no matter how good or bad they are, there’s always a cult audience ready to tell you every possible detail about that game.

And Action 52 is no different.

The unlicensed Nintendo Entertainment System and Sega Genesis title, is a perfect example of a bad idea in action. The brainchild of a guy named Vince Perri, the game made a bold promise: You could get 52 original games in a single cartridge, ensuring that you’d never again have to spend $50 on a single game.

Perri is said to have had the idea after witnessing his 9-year-old son play a pirated multi-cart from Taiwan, a device that had numerous titles installed.

“I happened to see my son playing an illegal product made in Taiwan that had 40 games on it. The whole neighborhood went crazy over it,” Perri said, according to a Miami Herald article from 1993, dutifully reproduced by CheetahmenGames.com. “I figured I’d do it legally. It’s obvious when you see something like that, you know there’s something there.”

There was one obvious problem with this line of logic: he didn’t have 52 games to sell. So he hired a couple of developers to make them for him. They didn’t have much in the way of time or money, and while it’s entirely possible they had talent, the lack of time or money ensured the talent would be hard to find.

Perri made the ultimate mistake that one could make when creating an original product—he mistook quantity for quality. But Perri was able to get a variety of investors to buy into his idea, ensuring that the idea had enough funding to go to market (at a price of $199, or as they liked to put it, $4 per game), but he skimped out on the only thing gamers really care about—the actual games.

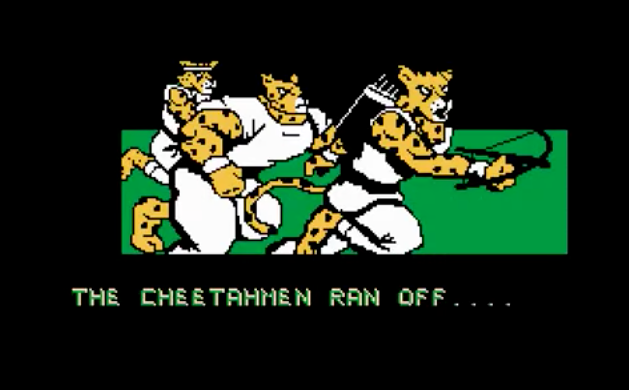

“Action 52 is just plain ugly, with Cheetahmen and Billy Bob being the only two games out of 52 to contain adequate artwork and visuals,” Hardcore Gaming 101 wrote of the final result in a review. “Some games are little more than a mess of pixels, but for most of them, they look like something you’d find in the margins of an eight year old’s math notebook. There’s also practically nothing in the way of animation, and backgrounds are extremely repetitive.”

A developer who worked on the project, going by the anonymous name of “Action 52 Developer #4,” explained that they were basically up against the wall trying to build numerous video games in a minimal amount of time.

“That’s right, 4 guys, 3 months, 52 games, no pressure. And, no money,” the developer wrote. “That’s until I talked the guys into letting me ask Vince for some kind of advance. I don’t recall the exact number, maybe $1,500. And that’s all I ever got paid for those long hours spent on this project.”

The most prominent game on the multi-pack was Cheetahmen, which Perri hoped to franchise and turn into a series of hit toys.

There are all sorts of stories about the games, Perri, and Action Enterprises flying around. Among them: that the developers of the game ripped off the code of a pirate cart and recoded it for their own needs; that Perri had $20 million at his disposal, but spent less than $100,000 on the game itself; that more than 1,500 copies of a Cheetahmen sequel were sold at a Florida warehouse for a dollar each in 1996; and, most embarrassingly, the vaporware system that the company announced at the Consumer Electronics Show in 1994.

That system was supposed to be able to play NES, Sega Genesis and Super NES games, and included both a built-in LCD screen and a built-in CD-ROM. It was the most obvious piece of vaporware ever created. The company, of course, disappeared without a trace soon after CES.

But a funny thing happened on the way to obscurity for Action Enterprises: A YouTube celebrity named the Angry Video Game Nerd (birth name James Rolfe) took on Action 52 in a two-part episode. The first episode focused on the first 51 games on the cartridge (all of them were awful), while the second gave lots of hate and mockery to Cheetahmen.

“Out of 52, I’m sure we’ll eventually find one that’s decent … I hope,” Rolfe says at one point in the first episode, only to soon learn that he was wrong.

Quickly, Action 52 became something of the video game version of my favorite movie, The Room.

Sure, it’s still awful, but people have sort of embraced the awfulness of both the concept and the the absurd backstory of its creation. In 2012, Rolfe even showed up in a Kickstarter video for Cheetahmen II, the unreleased sequel to the original game. (That whole situation drove some controversy over whether or not the Kickstarter’s creator, Greg Pabich, was running a scam—but in the end, the results ended up being legit.)

Perhaps the most notable part of the Action 52 saga is the remake project that came about in 2010, when game developers pledged to remake each of the 52 games on the infamous cartridge, with the goal of making the games good (or at the very least, playable). So far, 23 such remakes have been completed.

The thing to remember about terrible product ideas is that there was likely a point at each of these products’ creations where the idea seemed like a good one.

For example, a device that creates any scent you can think of is an innovative idea, if not a particularly useful one. The problem there was a lack of market research.

Action 52, for its part, was clearly a failure in execution, and if it had 52 good games, maybe we’d be hailing it rather than mocking it.

But that’s not what Perri made. Maybe he aimed too high, charged too much, or rushed his developers. But the result is this: Given the choice of drinking dog water or playing Action 52, most people would choose the dog water.

Or, at least, they should.

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook