The Old in the Forest: Wolf Trees of New England & Farther Afield

A New England wolf tree: White oak (photograph by Ray Asselin via his “Timberturner + Bowlwood Woodturning” blog, used with permission)

A New England wolf tree: White oak (photograph by Ray Asselin via his “Timberturner + Bowlwood Woodturning” blog, used with permission)

Old trees resonate with us because they seem to bridge our own animal-time and the other, slower schedules of the planet. While the antiquity of the most aged bristlecone pine, even the most aged quaking-aspen root mass (all praise the Trembling Giant!), doesn’t approach the deep time of stone, trees certainly link us to the mysterious clock of climate. We preoccupy ourselves with the day-to-day action of the weather; they’ve staked their survival on the bigger-picture rhythms of the atmosphere. Great trees are the go-betweens from the realm of flesh-and-blood to those of sky and rock. They’re also aloof witnesses to the frantic escapades of the human race—one reason that they can be such tangible touchstones for our own personal and social histories, and why the injury or death of a familiar old one can be so unsettling.

We commonly call ancient trees persisting in a landscape that’s dramatically changed within their lifespan “legacy trees.” In the Northeast, meanwhile, there’s a special brand of legacy tree found scattered in that region’s dramatically regrown forests: the “wolf tree.” In the strictest sense, wolf trees are those spared the axe during widespread Colonial-era deforestation in order to provide shade for livestock or mark a boundary. As second- and third-growth woods filled in abandoned pasture and farmland, these titans have become crowded by dense, spindly youngsters. Where those upstarts are tall and narrow, competing fiercely for canopy light, the wolf tree they surround has fat, laterally extended boughs and a comparatively squat trunk—a testament to the open, sunny country in which it once prospered.

Why “wolf?” Most suggest it stems from foresters comparing these ponderous relics to rapacious predators sapping sunlight and nutrients from the more economical (and less eccentric) timber swamping them. In Reading the Forested Landscape - which interprets New England’s countryside with historical ecology - Tom Wessels associates the name with lone wolves, outlaws in the face of civilization. (17) Regardless, the term is a good one: These trees, full of wildness, are as stirring to come upon as a fresh paw-print in the snow.

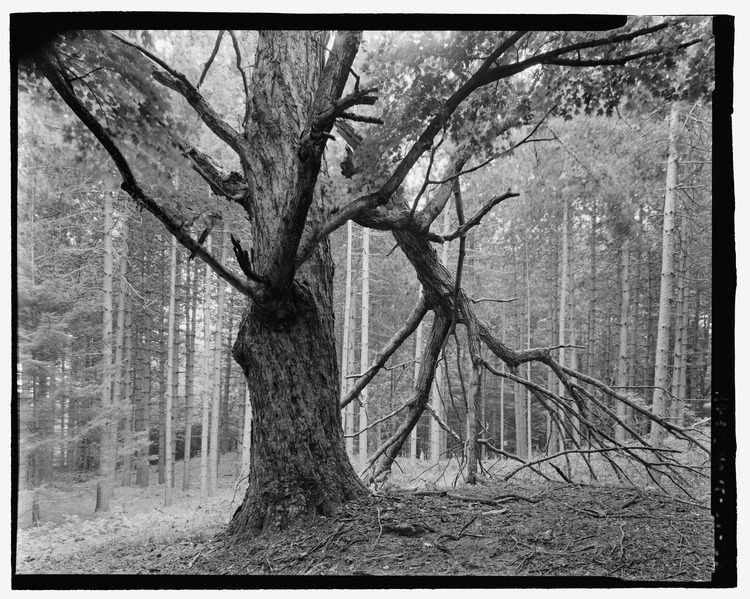

Wolf maple in a red-pine plantation, Vermont (photo by David W. Haas, NPS/via Wikimedia Commons)

Wolf maple in a red-pine plantation, Vermont (photo by David W. Haas, NPS/via Wikimedia Commons)

In his book, Wessels advocates the alternate moniker “pasture tree,” which does describe the history of many of these Northeastern wolf trees. While an 18th or 19th century farmer might completely clearcut a fertile valley to plant crops or grow hay, large tracts of the region’s rolling uplands—ridden with glacially deposited stones and boulders—were more roughly “improved” for grazing acreage. This logged-over landscape, called “bushpasture,” often featured big, solitary trees retained to shelter flocks and herds. (16) While any suitably large tree might be chosen, oaks figure prominently among New England’s wolf trees—unsurprising, given how widespread oak (and oak-chestnut) woodlands were in the stony hills and plateaus commonly converted to livestock range.

Touring upstate New York in the 1840s, the British writer Frederick Marryat marveled at the fast clip at which pioneers were felling the woods and documented the process by which future wolf trees were born (12):

“Occasionally some solitary tree is left standing, throwing its wide arms, and appearing as if in lamentation at its separation from its companions, with whom for centuries it had been in close fellowship.”

In the second half of the 19th century, many farms began to be abandoned, and post-agricultural forest regrowth began across large swaths of the Northeast. As Robert Thorson writes in Stone by Stone, a history of the region’s stone walls (16):

“Trees sprouted in old pastures like whiskers left uncut, enveloping their bordering stone walls in shade. Beginning about 1870, the forest area began to double every 20 years or so.”

To illustrate: Seventy-six percent of Worcester County in Massachusetts was in cultivation or pasture in 1876; roughly a century later, such open ground occupied just thirteen percent. (8)

An eastern white pine in Wisconsin, exhibiting the multi-trunked form shared by many of New England’s old-field pines

An eastern white pine in Wisconsin, exhibiting the multi-trunked form shared by many of New England’s old-field pines

In central New England, many old, open-grown eastern white pines represent second-generation wolf trees, dating from the early years of widespread farm abandonment in the region. As a sun-loving pioneer tree that can produce voluminous seed crops, white pine was well poised to invade the feral meadows (alongside other opportunistic species such as eastern red-cedar and common juniper). These old-field pines nourished a thrumming timber industry in the first decades of the 20th century. This harvest turned out mostly to be a one-time shot: Because they languish in shade, there weren’t pine saplings waiting in the understory to replace the mature trees felled, and furthermore, pines don’t sprout after cutting. So it was primarily hardwoods—red oak, black birch, white ash, and others—that took over once the big pines were logged, and it’s those broadleaf trees that now blanket much of the region. Enough wolf pines remain to speak to the post-agricultural old-field phase the landscape tried out for awhile. Many brandish multiple trunks, making them look like giant upturned tarantulas. And many, overtopped by the hardwoods, have been dead for years and stand as barren snags. (8,18)

Indeed, wolf trees of all stripes tend to be deteriorating, given the crowding and shading that now define them. Their heavy, wide-spreading limbs, nourished once by full sun, are now light-starved and too energetically costly to maintain. (For more insight into the region’s landscape changes, check out the online version of a classic, much-celebrated series of dioramas depicting a generalized history of central New England’s forests, housed at the Fisher Museum at the Harvard Forest.)

New England white-oak wolf tree and stone wall (photograph by Ray Asselin via his “Timberturner + Bowlwood Woodturning” blog, used with permission)

New England white-oak wolf tree and stone wall (photograph by Ray Asselin via his “Timberturner + Bowlwood Woodturning” blog, used with permission)

Plenty of phantoms mill about around wolf trees. Take a 350-year-old white oak in New England, snaking its dying branches through doghair maples and hemlocks. It summons up a whole gang of ghosts, and not just those of cattle or sheep or axe-wielding woodchoppers taking a breather under its canopy—older ones yet. There’s the ghost of lightning- and (especially) Indian-sparked fire, a force that, as in so many areas, helped maintain oak, intolerant of shade and slow-growing, amid a landscape capable of growing dense mixed-hardwood forest. Observers of the pre-colonial oak-chestnut woodlands of Northeastern uplands often commented on their remarkable openness, noting you “might drive a four-horse chariot in the midst of the trees.” (1)

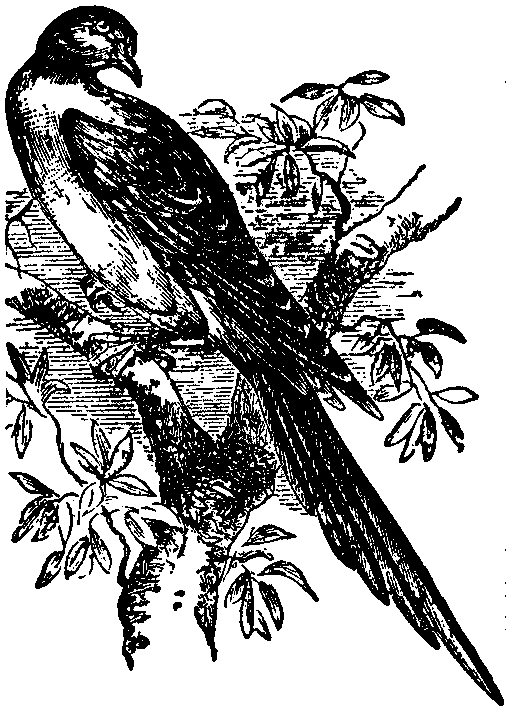

Another phenomenon besides fire, an avian one, may have been just as important in keeping white oaks around in New England. Passenger pigeons, once by far the most numerous bird on the continent (and maybe the planet), favored the acorns of red oaks over white, and existed in great-enough numbers to perhaps suppress the former to the benefit of the latter. (4) Furthermore, flocks of pigeons could be so enormous that the trees they roosted in sometimes collapsed under their weight. Such treefall would allow sunlight into an otherwise closed forest, providing good conditions for a seedling oak unable to survive in heavy shade.

The vanished passenger pigeon is intimately connected to oaks in the Midwest and the East (from The New Student’s Reference Work, v. 3, 1914, p. 1489/via Wikimedia Commons)

Like free-roaming ground fires, the pigeons are gone, but the old oak (on which the birds may have once congregated) conjures their spirit all the same. Surrendering our imaginations fully to flights of space-time, we might even sense in its presence the closing centuries of the Pleistocene, when blue jays and other acorn-eaters hastened the migration of this white oak’s ancestors northward from Ice Age strongholds in the Southeast. Oaks reclaimed the Northeast some 10,000 years ago as a warming, drying climate, which had already chased the continental ice sheet poleward, edged out boreal-style spruce forest. (1) Seen at the proper scale, trees travel: retreating as conditions adverse to their growth set in, advancing where their optimal habitat develops. And the thronging that wolf trees now endure reminds us of the quiet battles plants wage upon each other; of the dynamic, fluid nature of ecosystems; and of the dual role of the human being as animal within those ecosystems and as a force of disturbance upon them.

In September 1841, while traveling south through the haze-filled Rogue River Valley, members of the United States Exploring Expedition encountered an elderly Indian woman, intently “blowing a brand to set fire to the woods.” The small detachment of Navy officers and their associates had struggled during previous days over mountains covered by charred vegetation and through canyons filled with smoke, the result of native-set fires. Expedition artist Titian Ramsay Peale described the woman—who was dressed in a “mantle of antelope or deer skin” and wore a “cup-shaped” basketry cap—as “so busy setting fire to the prairie and mountain ravines that she seemed to disregard us.”

—Jeff LaLande & Reg Pullen (from Indians, Fire and the Land)

While the wolf trees of the Northeast may tell a fairly specific story of Euro-American land use, others exist in many other places—that is, if we consider a wolf tree as any open-grown stalwart now mobbed by younger woods. They’re particularly common wherever fire suppression (and, in some cases, the cessation of grazing) has converted savanna to forest. Find them, say, in such far-flung regions as the Midwest, the Cross Timbers, the Intermountain West, and the Mediterranean-climate valleys of the West Coast.

Like their counterparts in the New England uplands, Indians in Oregon’s Willamette Valley, such as the Kalapuya, burned prairies and oak savannas yearly. Here, the fire season was late summer and early autumn, before the fall rains commenced. These burns sometimes confounded Euro-American travelers, who were hard-pressed to find forage for their horses amid great sweeps of charred countryside. Nonetheless, settlers did notice the surging green-up of prairie grasses on the heels of these Indian fires, and celebrated the beauty of the flame-managed Garry-oak groves, which, in 1847, the pioneer Joel Palmer said appeared “like old orchards” from afar. (2)

Garry-oak savanna, central Willamette Valley

Garry-oak savanna, central Willamette Valley

As the anthropologist Robert Boyd has noted, the Kalapuya and other Western Oregon Indians apparently burned lowland valleys for a variety of reasons. The fires both improved their ability to locate deer and elk and enhanced the local habitat for these ungulates by promoting a lush growth of grass. Furthermore, aboriginal cultures here and in a number of other regions in the Far West implemented an autumn “circle deer hunt,” during which flames were used to flush and funnel game. In the Willamette Valley, Indians also used burning to improve the harvest of foods such as tarweed, hazelnuts, acorns, berries, camas, bracken, and grasshoppers, and they cultivated tobacco in ash beds. (2)

With the ebb of traditional Indian lifeways in the valley beginning in the mid-1800s, fire ceased to be an important landscape-sculpting force. Without regular burns or analogous disturbance, the Willamette appears to convert to forest, as evidenced by the steady invasion of old, airy oak stands by Douglas-firs, grand firs, and bigleaf maples. Douglas-firs, which are shade-intolerant, can colonize a sun-dappled oak savanna but, if other trees start growing up beneath them, will be ultimately unable to reproduce. Thus today, many a deep wood on the Willamette Valley floor has multiple cohorts of wolf trees: dead or waning old-growth oaks mixed with huge, wild-armed Douglas-firs that first seized the dying oak savanna—and both now thronged by younger trees.

Garry-oak wolf tree, Sauvie Island

Garry-oak wolf tree, Sauvie Island

Some Indians regarded Euro-American fire suppression in western Oregon’s valleys quizzically. As LaLande and Pullen write in their account of aboriginal burning in the southwestern part of the state (in Indians, Fire and the Land), “The change moved one Klamath man to complain to ethnographer Omer Stewart that ‘[n]ow I just hear the deer running through the brush at places we used to kill many deer.’ He pointed out that when the brush ‘got as thick as it is now, we would burn it off.’” (9)

I grew up blocks from an overgrown southeastern Wisconsin oak opening: Downer Woods, an 11-acre forest on the grounds of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. Its grandest trees are scattered Halloween oaks—white, red, and bur—that wolfishly hark back to a bygone landscape. Evidence suggests these hoary, twisted monarchs seeded back in the mid-to-late 1700s in an Indian-burned landscape. By the 1830s, the oaks—which likely escaped harvest due to their uncommercial form—presided over pasture for decades. Once the land became a college campus, no longer swept clear either by fire or rubbery-lipped grazers, trees and shrubs invaded the former parkland. (14) Today, ashes and basswoods form a closed-canopy wood studded by those monumental wolf oaks.

The wolf oaks of Downer Woods, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee campus

The wolf oaks of Downer Woods, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee campus

Just as a wolf tree is marooned in heavy woods, many other legacy trees stand out for their isolation in drastically altered environments. In the Pacific Northwest, some record-sized conifers tower, spared and orphaned, in vast clearcuts (where they’re almost certainly doomed to topple in wind): Consider Big Lonely Doug on Vancouver Island, for example, recently deemed the second-biggest Douglas-fir in Canada. And there’s the Lone (or Sentinel) Cypress, a huge old-growth bald-cypress that once served as a navigation marker on the marshy shores of Lake Okeechobee and today stands in the town of Moore Haven, the lake (diminished in extent by water-control measures) now several miles away.

Cousin to the old pasture trees of New England are the centuries-old oaks, beeches, yews, and other veterans of (old) England’s “greenwood.” These behemoth ancients also register the hand of humans upon the countryside: Many reflect years of pollarding or coppicing (the repeated cutting of a trunk to keep harvesting young, straight-growing wood from the same tree), and grow in woodlands once intensely pastured or royal forests preserved as exclusive hunting retreats. Some are truly celebrated monuments in Britain, including the Major Oak of Sherwood Forest (in folklore, the shelter of Robin Hood and his Merry Men) and the many sylvan elders of the Savernake Forest, such as the Big Belly Oak and the King of Limbs.

The Big Belly Oak of Savernake Forest (photo by Jim Champion/via Wikimedia Commons)

The Big Belly Oak of Savernake Forest (photo by Jim Champion/via Wikimedia Commons)

As in the Northeast, these trees can starkly reference our own history, our own touch upon the landscape. But the temporal power of the legacy tree extends beyond its reminders of historical time—that of farmers, shepherds, hangings, and crossroads. It also displays in lonely solitude the majestically drawn-out aging and dying and decay process that any tree showcases if let alone. In these processes, it evokes what Jay Griffiths has termed “wild time” (7): that primal dimension enfolding rock, air, water, wood, and flesh against which the frenetic and neurotic human clock struggles, ultimately in vain.

“The wolf trees are a forest anachronism—old-growth features in a young forest,” Michael Gaige, a New York-based conservation biologist with a passion for “wolves,” has written. (5) Essentially they inject a little old-growth flavor into second-growth woods. They exhibit some classic characteristics of ancient trees, architectural features common across many species. These include heavily plated or flaky bark; patches of bald wood on the lower bole; a spiral grain and/or sinuous wave to the trunk; swollen bases or exposed, buttressed roots; collared clefts and cavities; and a canopy composed of relatively few, heavy, twisted branches. And many trees—notably conifers, but also oaks and some other hardwoods—often display a jagged, multi-pronged deadwood crown: a “staghead” or “spiketop” tree. (11,15,18) These structural and textural features arise from the aging cycle, interactions with neighboring trees, and the tattoos and war wounds a long-lived tree accumulates from its environment.

Sugar-maple wolf tree snag (photograph by Ray Asselin via his “Timberturner + Bowlwood Woodturning” blog, used with permission)

Sugar-maple wolf tree snag (photograph by Ray Asselin via his “Timberturner + Bowlwood Woodturning” blog, used with permission)

With their great mass and their knotty, fissured surface, wolf trees call to many creatures (flying squirrels, woodpeckers, etc.) in ways that comparatively prim, proper, and structurally simple young trees don’t. Studies—from the New England woods to a commercially cut coast-redwood forest in Mendocino County, California—suggest wolf trees and other old-growth relics support greater wildlife diversity and use than the sprightlier trees around them. (10) In Vermont, Gaige noted mammals as big as coyotes denning in wolf trees. (6) (Any big tree can be a wildlife beacon: A study in the Willamette Valley showed the importance to birds of standalone old-growth Garry oaks in farmfields and pasture. [3] The island-like habitat formed by such open-country trees is similar to that of wolf trees, adrift as they are in second- or third-growth of strikingly different stature.)

The ecological services a wolf tree provides aren’t confined to its lifespan. Dead trees—particularly big ones that rot over length periods, like American chestnut in the East and western red-cedar in the Northwest, or a conifer flash-killed by fire and left as a slow-decaying snag—continue to offer habitat and forage for countless organisms, from wood-processing fungi to nesting raptors, on a scale of decades or centuries.

Ponderosa-pine snag, east-side Cascade Range, Oregon

Ponderosa-pine snag, east-side Cascade Range, Oregon

Toppled wolf oak (photograph by Ray Asselin via his “Timberturner + Bowlwood Woodturning” blog, used with permission)

Toppled wolf oak (photograph by Ray Asselin via his “Timberturner + Bowlwood Woodturning” blog, used with permission)

Legacy trees suggest the multiple identities of a given landscape. The tombstone snags of widely spaced ponderosa pines looming in a thick, post-fire-suppression wood of fir and larch on the eastern slopes of the Cascade Range describe a spectral savanna with a contemporary conifer forest superimposed upon it. The wolf oaks of New England echo pre-Columbian fire- and pigeon-tended woodlands as well as erstwhile colonial bushpasture. So wolf-tree country is overgrown rangeland, overgrown savanna—but also just a new kind of modern-day forest, too, a dense, dark one sprinkled with the occasional noble hulk to lock you right into time, and to take you right out of it.

Bush Pasture Park, Salem, Oregon: Oak savanna–>Pasture–>City park (open-grown Garry oaks intact)

References

- Bonnicksen, Thomas M. America’s Ancient Forests: From the Ice Age to the Age of Discovery. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2000.

- Boyd, Robert. “Strategies of Indian Burning in the Willamette Valley.” Indians, Fire and the Land in the Pacific Northwest. Ed. Robert Boyd. Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University Press, 1999. 94-138.

- DeMars, Craig, et al. “Multi-scale Factors Affecting Bird Use of Isolated Remnant Oak Trees in Agro-ecosystems.” Biological Conservation 143 (2010): 1486-1492.

- Ellsworth, Joshua W. and Brenda C. McComb. “Potential Effects of Passenger Pigeon Flocks on the Structure and Composition of Presettlement Forests of Eastern North America.” Conservation Biology 17 (2003): 1548-1558.

- Gaige, Michael. “A Place for Wolf Trees.” Northern Woodlands Spring 2011.

- Gaige, Michael. “Wolf Trees: Elders of the Eastern Forest.” American Forests Fall 2014.

- Griffiths, Jay. A Sideways Look at Time. New York: Jeremy P. Tarcher, 2004.

- Jorgensen, Neil. A Sierra Club Naturalist’s Guide to Southern New England. San Francisco: Sierra Club Books, 1978.

- LaLande, Jeff and Reg Pullen. “Burning for a ‘Fine and Beautiful Open Country’: Native Uses of Fire in Southwestern Oregon.” Indians, Fire and the Land in the Pacific Northwest. Ed. Robert Boyd. Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University Press, 1999. 255-276.

- Mazurek, M.J. and William J. Zielinski. “The Importance of the Individual Legacy Old-growth Tree in the Maintenance of Biodiversity in Commercial Redwood Forests.” U.S. Forest Service Pacific Southwest Research Station Report, 2003.

- Pederson, Neil. “External Characteristics of Old Trees in the Eastern Deciduous Forest.” Natural Areas Journal 30: 396-407.

- Perlin, John. A Forest Journey: The Role of Wood in the Development of Civilization. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1989.

- Perry, David A., Ram Oren, and Stephen C. Hart. Forest Ecosystems. 2nd ed. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press, 2008.

- Salamun, Peter J. “A Botanical History of Downer Woods.” The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Field Stations Bulletin 5.2 (1972): 1-9.

- Stahle, David W. “Tree Rings and Ancient Forest History.” Eastern Old-Growth Forests: Prospects for Rediscovery and Recovery. Ed. Mary Byrd Davis. Washington, D.C.: Island Press, 1996. 321-343.

- Thorson, Robert. Stone by Stone: The Magnificent History of New England’s Stone Walls. New York: Walker & Company, 2002.

- Wessels, Tom. Reading the Forested Landscape: A Natural History of New England. Woodstock, VT: The Countryman Press, 1997.

- Wessels, Tom. Forest Forensics: A Field Guide to Reading the Forested Landscape. Woodstock, VT: The Countryman Press, 2010.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook