The Women Who Rose High in the Early Days of Hot Air Ballooning

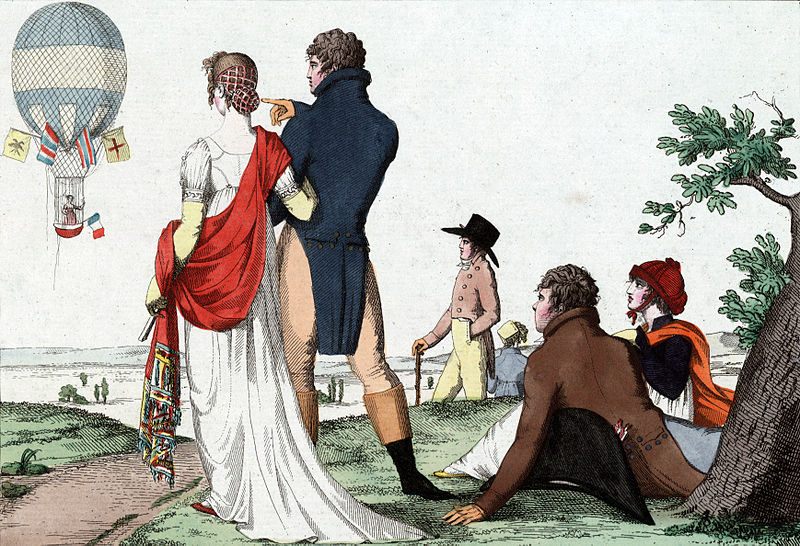

Spectators watching French balloonist Jeanne-Genevieve Labrosse ascending in a balloon on 28 March 1802. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

On the evening of July 6, 1819, British tourist John Poole was in his Paris hotel room when he witnessed something spectacular and shocking. A woman, Sophie Blanchard had ascended to the sky in a balloon, and was set to discharge some fireworks from the basket. But instead, as Poole recounted, this happened:

For a few minutes, the balloon was concealed by clouds. Presently it reappeared, and there was seen a momentary sheet of flame… In a few seconds, the poor creature, enveloped and entangled in the netting of her machine, fell with a frightful crash upon the slanting roof of a house in the Rue de Provence…and thence into the street, and Madame Blanchard was taken up a shattered corpse!

This dramatic death Sophie Blanchard, pioneering balloonist, signaled the beginning of the end of “balloon-mania,” which swept continental Europe and England for almost 40 years and involved women playing crucial roles.

Balloonist Sophie Blanchard. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

In 1784, just two years after Joseph Montgolfier invented the hot air balloon, 19-year-old Frenchwoman named Elisabeth Thible was the first woman to go on an untethered balloon flight. On June 4, 1784, a painter and amateur aeronaut named M. Fleurant and the Count Jean-Baptiste de Laurencin were scheduled to go up in La Gustave, named after King Gustav III of Sweden, who was there in Lyon to watch the spectacle. However, the Count got nervous and gave his spot to Thible, said to be a widowed opera singer. Thible, dressed as the goddess Minerva, climbed into the balloon to the delight of the assembled crowd, who were shocked to see a woman braving the open sky. According to historian S.L. Kotar:

The descent went smoothly, but as the balloon touched ground, it burst open at the top and the canvas toppled upon them. Fleurant cut his way out with a knife and went to rescue his “fearless companion,” only to find her already out of danger.

Fleurant credited Thible with the 45-minute flight’s success, recounting how she had bravely fed the firebox during the entire trip.

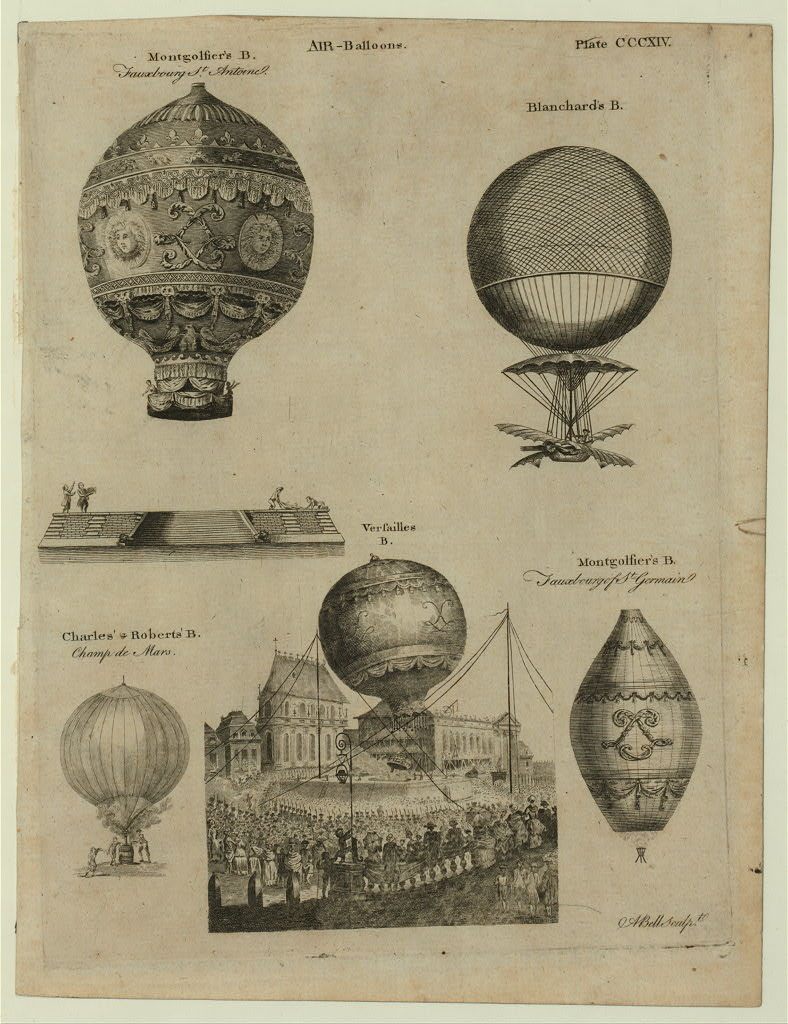

A 1784 print showing different balloon designs in France. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Over the next decade, France would be plunged into civil war that would spill beyond French borders. During this turmoil, a new superstar aeronaut emerged on the scene. In 1797, Andre-Jacques Garnerin thrilled war-weary Europe when he became the first person to parachute out of a balloon over the Parc Monceau in Paris. He was made the “Official Aeronaut of France.“ In 1798, the tireless self-promoter decided to pull his most daring stunt yet: to bring a woman up in the air. (It seems everyone had forgotten about brave Elisabeth Thible).

When the Central Bureau of Police got wind of the upcoming stunt, Garnerin was forced to appear in front of officials, who feared the implications of a man and woman being alone together. They also were concerned that air pressure might damage a lady’s delicate undercarriage. The Bureau issued an injunction against Garnerin, only to have it overruled by the Minister of Interior and Police, who stated that there “was no more scandal in seeing two people of different sexes ascend in a balloon than it is to see them jump into a carriage.”

The young woman chosen by Garnerin is known to history as simply Citoyenne Henri. The ascent, on June 4, 1798, drew a large crowd to the park, and the flight went smoothly. Citoyenne Henri, much like Elisabeth Thible, enjoyed brief fame before plunging back into anonymity.

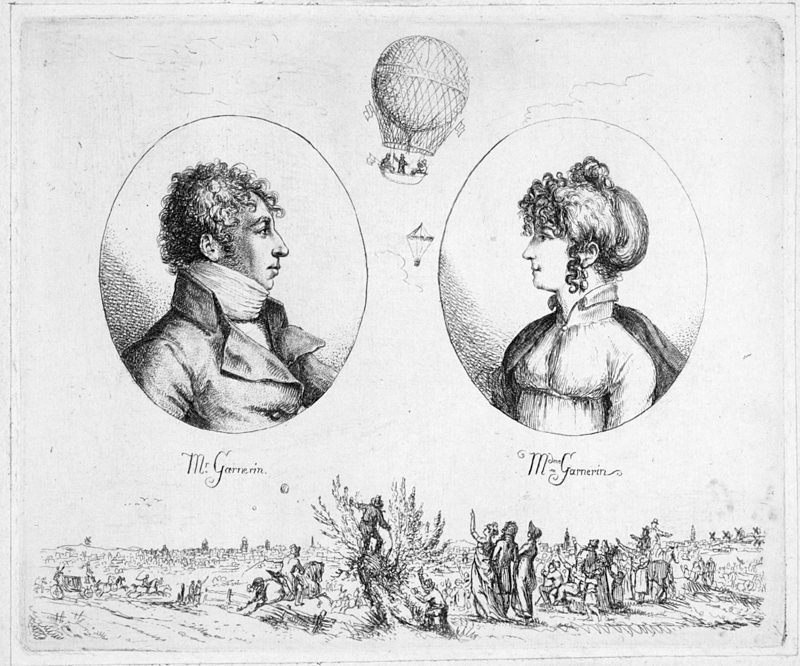

Andre-Jacques Garnerin with Citoyenne Henri in a controversial balloon flight on 8 July, 1798. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

The first golden age of female flight was soon to come, with the Garnerin family leading the way. Garnerin’s wife, Jeanne-Genevieve Labrosse, originally his star pupil, became the first woman to fly solo on November 10, 1798. A year later, she was the first woman to parachute, from an altitude of 900 meters (2,953 feet). Together, the Garnerins performed throughout Europe and the UK, pioneering “acrobatic displays, parachute drops and night-flights with fireworks.” They were soon joined by his niece Elisa (Lisa) Garnerin, who would become a celebrated solo balloonist and parachutist, with 39 recorded descents.

Elisa Garnerin’s lengthy solo career would be overshadowed by her great rival Sophie Blanchard. The darling of early aeronautics, the tiny, “bird like” Sophie was first taken up in a balloon by her much older husband, the aeronaut Jean-Pierre Blanchard, in December of 1804. Nearly mute on the ground, she was so thrilled to fly that her first words in the air were “sensation incomparable!” She was soon touring as a soloist with her husband, contributing to the party atmosphere of public celebrations around Europe. After her husband’s death, Blanchard continued to tour alone, becoming the “Aéronaute des Fêtes Officielles” of Napoleon.

Garnerin with his wife, Jeanne Geneviève Labrosse. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Blanchard’s exploits became legendary. “Only comfortable in the air,” Sophie became famous for her night ascents across Europe. She set off fireworks from her balloon to celebrate the 1810 marriage of Napoleon and Marie-Louise, and dropped leaflets over Paris to announce the birth of their son. She toured Italy, Germany and the UK. Blanchard was fearless to the point of recklessness—she was knocked unconscious when she flew too high to avoid a hailstorm, she would fall asleep in her balloon for hours, and suffered nosebleeds and frostbite when she ballooned over the Alps to celebrate the Emperor’s birthday. A true artist, she wore eye-catching bright colored feathered hats, and flattering white cotton empire style dresses with long, billowing sleeves to protect her hands. Most amazing of all was her special balloon, described by the historian Richard Holmes:

She commissioned a much smaller silk balloon, capable of lifting her on a tiny, decorative silver gondola. This was shaped like a small canoe or child’s cradle, curved upwards at each end but otherwise quite open. It was little more than three feet long and one foot high at the sides. … When she stood up, grasping the balloon ropes, the edge of the gondola did not reach above her knees. It was virtually like standing in a flying champagne bucket.

After Napoleon’s ousting in 1814, Blanchard switched from imperialist to monarchist and became the “Official Aeronaut of the Restoration.” Her night flights became more and more technically daring and dramatic:

Her small balloon lifted more and more complicated pyrotechnical rigs, with long booms carrying rockets and cascades, and suspended networks of Bengal lights, all of which she would skillfully ignite with extended systems of tapers and fuses. At the height of these displays, her small white figure and feathery hat would appear like some unearthly airborne creature or apparition, suspended several hundred feet overhead in the night sky, above a sea of flaming stars and colored smoke.

It all came crashing down on July 6, 1819, when Blanchard’s balloon caught fire over Paris and she fell to her death. Her untimely end led one unsympathetic critic to quip, “A woman in a balloon is either out of her element or too high in it.”

French balloonist Sophie Blanchard, standing in the decorated basket of her balloon during her flight in Milan, Italy, in 1811. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Although balloon-mania subsided, women continued solo flights that astounded their male counterparts. One example is the brilliant, scientifically gifted Wilhelmine Reichard, the first German woman to make a solo flight in 1811. Along with her husband, Johann, Reichard made many scientific observations and notations while in the air. She did solo flights until 1820, becoming a darling in the German press, lauded for her boldness and courage.

There was also the lovely cockney teenager known as Miss Stocks, who shocked English patriarchs in 1824 when she survived a nasty crash that killed Thomas Harris, the male pilot. To reassure themselves, male onlookers convinced themselves that Harris had died in an act of chivalry, protecting Miss Stocks from the full impact of the fall.

The end of the 19th century would see a resurgence of female balloonists and aerialists, particularly in America and England. Women like Lizzie Ilhing Wise, the golden haired inventor “Madame” Carlotta (Mary) Meyers, Leila Adair, Leona Dare, Jenny Van Tassel, and Mrs. Graham would all become famous for their exploits in the sky. Together, they would pave the way for the pioneer female aviators and astronauts of the 20th and 21st centuries.

Update 1/26: In an earlier version of this article, the wrong year was cited as the final year of Reichard’s solo flights. We regret the error.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook