The Year in Grossness

2018 was chock-full of nauseating delights.

What do we mean when we talk about “grossness”? Maybe an egregious oversight, a miscarriage of justice, or something that’s plainly, glaringly, indefensibly bad.

Sometimes, yes, we do mean those things. Other times, we mean something entirely different, and much simpler: “Grossness” as something to be celebrated or reveled in—something spectacularly crude, or joyously vulgar. Icky, in a fun way.

This year presented no shortage of moments of stomach-churning wonder. Here are some of the things that made us queasiest in 2018.

Behold, Latrines (and Coffins) Full of Ancient Poop

If you flush a toilet, you probably expect the foul stuff to snake its way through a labyrinth of pipes and eventually vanish during the wastewater treatment process. Folks who squatted at latrines made from barrels in Renaissance Denmark made no such assumptions—and their centuries-old poop is still hanging around. Archaeologists dug up a latrine in Copenhagen to learn more about local trade and eating habits. The poop held a surprising amount of wisdom—and, yes, it was still stinky.

In 2018, researchers also sifted through feces in pursuit of traces of parasites from the ancient city of Ephesus, in present-day Turkey, and studied long-dropped deuces in Bahrain, Jordan, Lithuania, and the Netherlands. Other teams came across sewage that had been leaking into a sealed sarcophagus buried beneath the streets of Alexandria, Egypt, for 2,000 years.

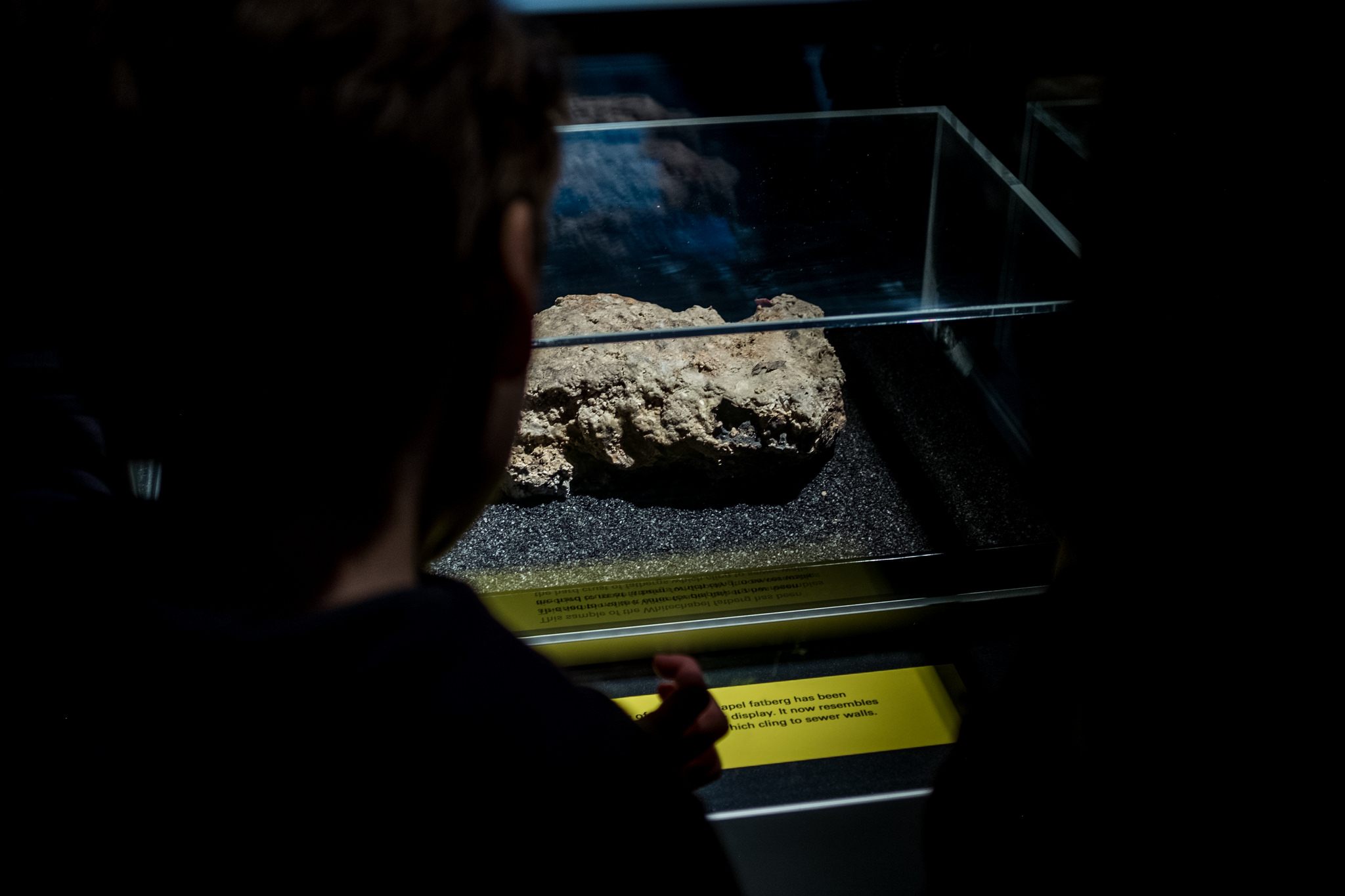

Fatbergs, Fatbergs, Everywhere

2018 was a big year for fatbergs. These sewer-clogging hunks of fats, oils, and pipe-mangled trash gained some measure of fame this year when one chunk of a behemoth recently hauled up from the streets beneath the Whitechapel neighborhood ended up on display at the Museum of London. Another gloopy monster, known as the South Bank fatberg, was the subject of a Channel 4 series, Fatberg Autopsy: Secrets of the Sewers. In 2019, cities around the world will continue to work to combat these big, festering problems.

Animals Stuck Inside Other Animals

It’s no fun to have something stuck in your schnoz. Even boogers can be a bother, so it’s likely that this Hawaiian monk seal was pretty uncomfortable when an eel dangled from his nose. The slippery creature had gotten wedged deep inside the seal’s nasal passage, and researchers yanked it out with a “slow, steady pull.”

Animals frequently end up inside other animals: Ones that feast on other creatures often die with parts of their meal still in their bellies, and fossilized remains in animals’ stomachs sometimes help researchers identify previously unknown species. But the dangling eels are a different situation. The scientists had seen these eel-afflicted seals before, and they’re not quite sure how the creatures get up there. Perhaps that’s a mystery to solve next year.

Some Mushrooms Look Like Dog Penises

When researchers recently set out to make an atlas of the fungi of North America, they had to include a few unsavory selections, including the Mutinus caninus, infamous for its pinkish, fleshy appearance and spermatic odor. Maybe there’s something to be said for an apt descriptor, however off-putting.

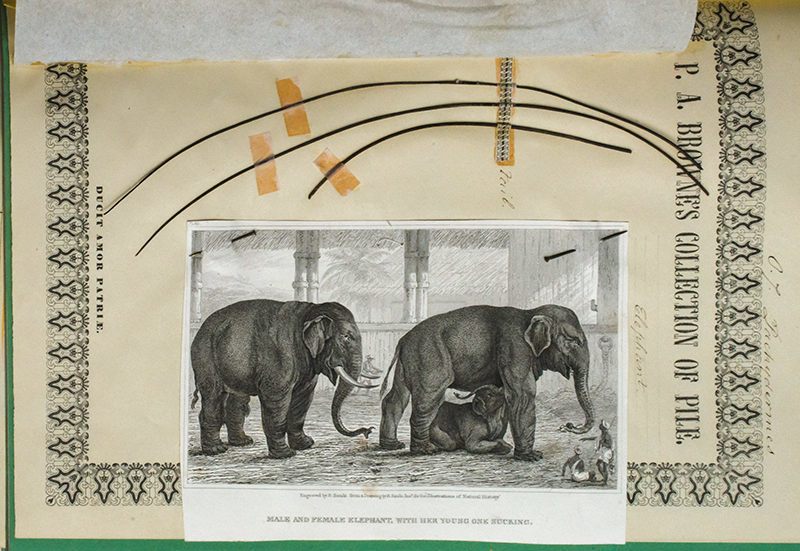

A Naturalist Collected an Enormous Trove of Hair

Peter A. Browne wanted to get his hands on fur or whiskers, wherever they sprouted. In the mid-19th century, he sought whorls of wool, presidential tendrils, and more, from most any creature across the globe. He carefully fastened his hirsute haul into annotated scrapbooks. These were nearly lost to the garbage dump in the 1970s, when a last-minute save kept them at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, where they were on display in a hair-raising exhibition this fall.

People Pressed Boogers Between the Pages of Their Books

When we asked Atlas Obscura readers to tell us about the treasures they found pressed inside books, we got some truly charming responses. One person stumbled across black-and-white photos, carefully affixed with yellowing tape; another person found a four-leaf clover, which luckily survived untold years intact. But readers came across gross stuff, too, including smeared boogers. If you absolutely must pick it and flick it, please leave the books out of it.

Cemetery Soil is Full of Gnarly Stuff

Cemeteries are a little like landfills, full of bodies instead of trash. Earlier this year, my former colleague Sarah Laskow wrote about cemetery soils, otherwise known as “necrosols,” which often contain all sorts of icky things, from pathogens such as drug-resistant E. coli to the chemicals used for embalming corpses. These and other contaminants can spread if cemeteries flood, but don’t let me be a huge humbug—though we’re running out space to bury people around the world, cemetery soil likely won’t be death of us.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook