The Respected Oxford Professors Who Say They Time Traveled

Two Victorian academics believed they saw Marie Antoinette at Versailles.

On a hot August afternoon in France, 1901, Miss Elizabeth Morison and Miss Frances Lamont, on holiday from England, took a trip to visit the Palace of Versailles, a former royal residence some twelve miles west of Paris. “We went by train,” they would later recall, “and walked through the rooms and galleries of the Palace with interest.” But it was not to be the pleasant day out that the ladies had anticipated.

As they started to explore the gardens, an inexplicable feeling of depression descended upon them, a melancholic atmosphere they described as “a dreamy haziness” and “eerie and unpleasant.” They began to encounter people clothed in strange attire. They saw “two men dressed in long greyish-green coats with small three-cornered hats,” and later a man whose “face was most repulsive, —its expression odious. His complexion was very dark and rough.” Passing over a bridge, they found: “a lady was sitting. I supposed her to be sketching. She turned and looked full at us. Her dress was old-fashioned and rather unusual.” Eventually, they found their way out of the gardens, and returned to their accommodation in a daze.

The oddness of their experience stayed with them. Later, returning to the palace to retrace their steps, they found this impossible. Buildings had changed, lanes had disappeared, and the bridge was no longer present. In fact, the whole layout was unfamiliar. Through diligent research, Morison and Lamont came to believe that, on that fateful day, somehow they had experienced the grounds as they had been in the late eighteenth century, and that the lady they had come across had been the infamous Queen Marie Antoinette.

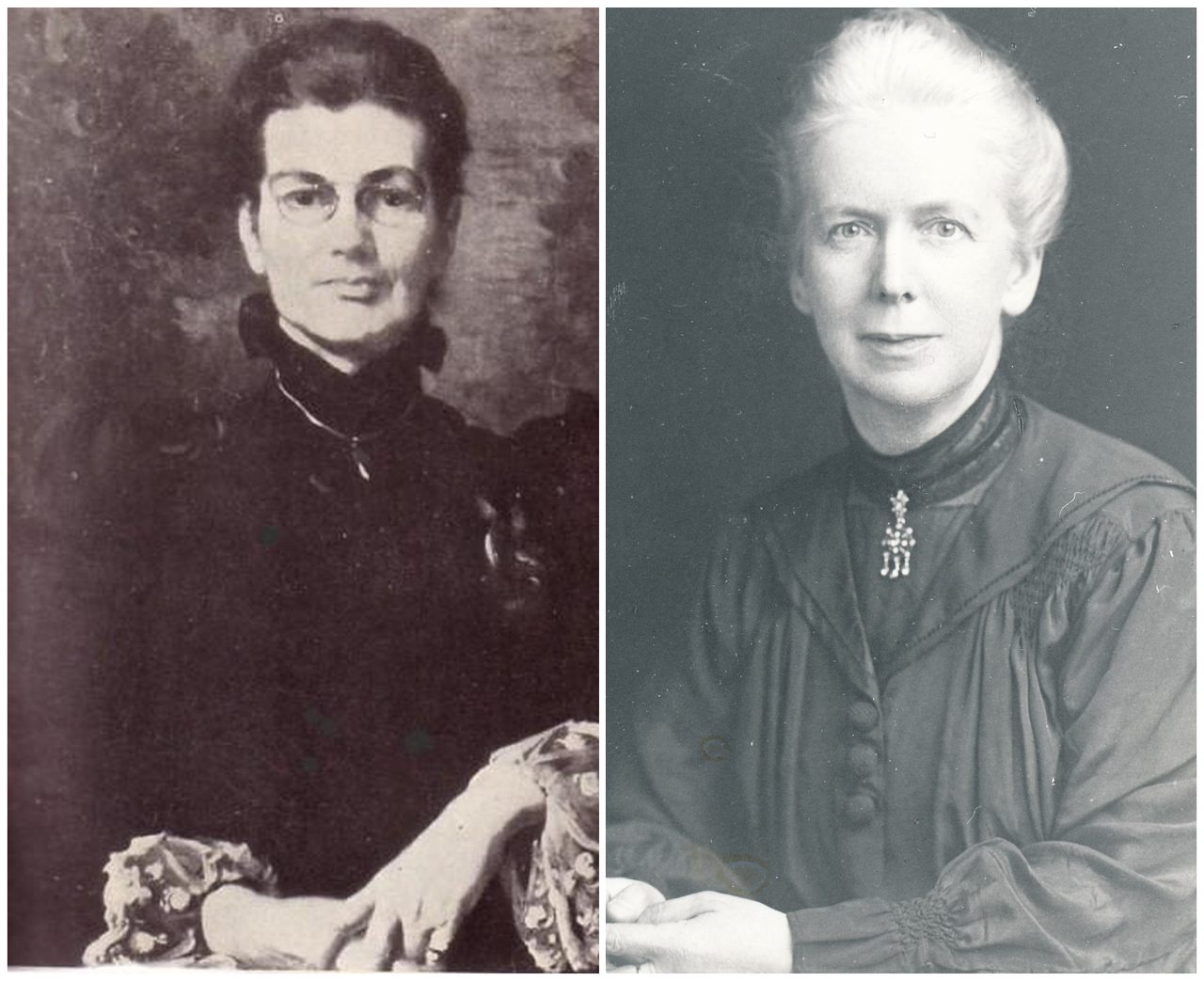

The story was so extraordinary that they decided to document a full account in book form. That account, titled An Adventure, was published in 1911. It became the literary sensation of its day, running to numerous editions. As incredible as the tale was, perhaps the most astonishing part was yet to be revealed, for Morison and Lamot did not exist. The real authors of An Adventure were Eleanor Jourdain and Charlotte Moberly, the Principal and Vice-Principal, respectively, of St Hugh’s College, University of Oxford—two highly esteemed academics hiding their names to protect their identities.

“St Hugh’s had been founded in 1886 for the daughters of poor clergyman,” explains a tutorial fellow at the present-day college who wishes to remain anonymous in order to avoid readers contacting him directly concerning the case. Charlotte Moberly served as the college’s first ever Principal. “Moberly wasn’t somebody who had a considerable scholarly background,” he says, “she was educated, but she didn’t have anything in the way of a degree. Jourdain was a different kettle of fish. She was formally qualified.” St Hugh’s was the reason for the ladies’ trip to France. As the professor explains: “Moberly wanted a vice principal who would ultimately be able to take over from her. Eleanor Jourdain was in the running for that role. Moberly wanted to get to know her. And they formed a very close friendship.”

As part of their investigation into their strange experience, Moberly and Jourdain contacted the Society for Psychical Research (SPR). Founded in 1882, the SPR’s mission is to “conduct scholarly research into human experiences that challenge contemporary scientific models.” A registered nonprofit with an elected council, the organisation remains well respected for its dispassionate investigations and diligent research. “There’s quite a few letters backwards and forwards [between the women and SPR],” affirms SPR Archive Officer Melvyn Willin.

According to Willin, “time slip” stories, as they are referred to, are fairly common. The Versailles incident, however, he says, “would probably be in the top three. Some would argue it’s the number one. It’s a very important case. Undoubtedly, they would have received a lot of pestering from the press, from the public, and from psychical researchers.” As Willin notes, the SPR member’s responses to Moberly and Jourdain’s story varied widely, with no consensus being reached as to its legitimacy. Doubters proposed many mundane explanations for the ‘time-slip,’ ranging from fancy dress parties to heat exhaustion and even folie à deux, none of which prevented An Adventure from becoming a certified hit.

Moberly and Jourdain would have likely wanted to keep their true identities secret due to concerns about how senior university figures might react should they attract controversial attention to the institution, which remained largely conservative. So how did the ladies’ true identities become known? “It was not a very closely kept secret,” explains the Oxford tutorial fellow, “and Jourdain not only discussed the incident amongst themselves, but they also discussed it with their students.” In fact, both women had a long history of supernatural experiences, which they did not hide from their pupils.

The tutorial fellow has a theory as to why this might have been. “Women were viewed as second class students,” he says, postulating that Moberly’s and Jourdain’s desire to be seen as legitimate academic figures could link to their outspoken beliefs in the supernatural. Moberly, in particular, may have felt self-conscious as to her lack of formal credentials. Denied equal respect from their male peers, it’s possible that the two women could have turned to alternative means of establishing authority at a time when interest in spiritualism was at its height. At St Hugh’s, women didn’t have as many established patterns of behaviour or teaching when compared to the entrenched protocols for the males. “This is a new institution,” says the professor, “it’s a little bit different from other colleges. My hunch has always been that this connects to An Adventure.”

Despite the critical backlash, the ladies’ academic careers continued. In 1915, Moberly retired as Principal, to be succeeded in her role by her close friend, Jourdain. The younger woman’s reign was not a happy one. “She was too strict,” he adds, “and that led her into conflict with some of the younger fellows.” Things came to a head in 1923, when many tutors resigned over the disputed sacking of a fellow teacher. When it became apparent to Jourdain that she would be asked to step down, she suffered a fatal heart attack. She died on April 6, 1924. Moberly outlived her by another thirteen years.

According to Oxford’s fellow, the two women remain honoured figures in the college’s history. “There are massive portraits of both of them in the room where the fellows have breakfast,” he says, “Moberly is remembered as the founding principle, and Jourdain did a lot of work to establish the college.” In university biographies and histories, however, An Adventure is only ever mentioned fleetingly, if at all, and you will find no reference to it on the St Hugh’s website. That aspect of the women’s legacy, it seems, is not so well celebrated. Moberly and Jourdain remained close friends throughout their lives, and are buried just a few feet from each other in Wolvercote Cemetery, Oxford. They leave behind a remarkable book—a bestseller of its day which continues to enthral and perplex.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook